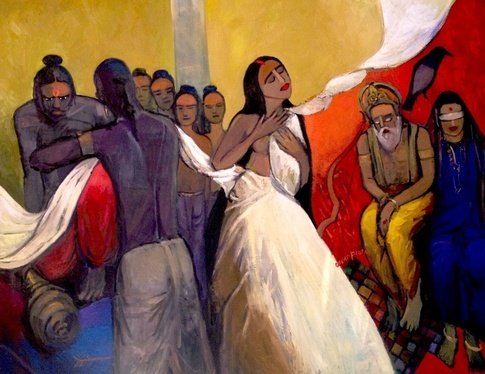

“Go into the assembly and ask if Dharmaraja had become a slave before he staked me.”

– Irawati Karve, Draupadi: Introduction, Yuganta

Irawati Karve’s Draupadi in Yuganta (1968) raises “difficult and complicated” legal and moral issues while the Kaurava men start pulling off her sari. In Karve’s version, as each sari is pulled off another appears in its place and the discussion continues, as opposed to Vyasa’s The Mahabharata which offers a deafening silence. By asking this question, Draupadi, a woman, transcends the domestic sphere and contests the “rights of a master over a slave and a slave over his wife.” On the one hand, if Bhishma argued that her husband, even as a slave, maintained his right over her, her slavery would be confirmed. On the other hand, if he argued that her husband no longer had any right over her, “then her plight would be truly pitiable” because abandoned wives and widows had an extremely low social standing and lived “wretchedly in the house of their father”.

She managed to illuminate the injustice prevalent in the court and its laws. She questions traditional standards of morality and legal prescriptions which render the marginalised powerless, such as women and slaves. In this, she emerges as a shining bold woman, back in the time of complete subjugation. Valmiki’s The Ramayan does not posit a female protagonist as strong as Draupadi, thus, a contrast surfaces between her and Sita. Draupadi establishes herself as a rational being and challenges her patriarchal authority. This is an insult to her male superiors as her interrogation had put all of them in a dilemma; Bhishma hung his head and Dharma was ready to die of shame. The position of the Kshatriya woman becomes clearer as Karve highlights the same in a sarcastic tone:

“Draupadi was standing there arguing about legal technicalities like a lady pundit when what was happening to her was so hideous that she should only have cried out for decency and pity in the name of the Kshatriya code.”

Karve calls Draupadi “a lady pundit” who is able to express discontent with traditional norms of legal and moral proceedings and justify her plight. While her interrogation brings her little relief, if she had played the role of a victim and cried for help, she would probably have been rescued by virtue of the deeply patriarchal Kshatriya code which takes pride in presenting men as ‘rescuers’. This allows the post-modernist audience to view The Mahabharata as a social tragedy, wherein, a woman is given no credit for her skills but appreciated for subservience. Karve further analyses the event when Dharma called Draupadi a ‘lady pundit’ or Brahmin and excluded her from Kshatriyas. This sentiment of his manifests when he condemns her to hell and refuses to even stop a minute when she falls in the Swarga Arohan Parva from Mount Kailash.

Draupadi is brave, patient and wise. She recognizes the social structure which would restore her social position if her husbands’ dignity is restored and hence, uses her boons to do so. She is indeed a lady pundit, capable of not only distinguishing but also establishing right apart from wrong. Although, on the surface it seems as though she caused the war but just like Helen of Homer’s The Iliad, she is a victim of social expectations and men’s egos. Yet, she is able to raise doubt and shame in the minds and hearts of her social superiors (patriarchal authority and elders) and plays the role of a lady pundit, dauntless and sagacious, instead of a damsel in distress.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://thefablesoup.wordpress.com/2015/11/25/irawati-karves-lady-pundit/