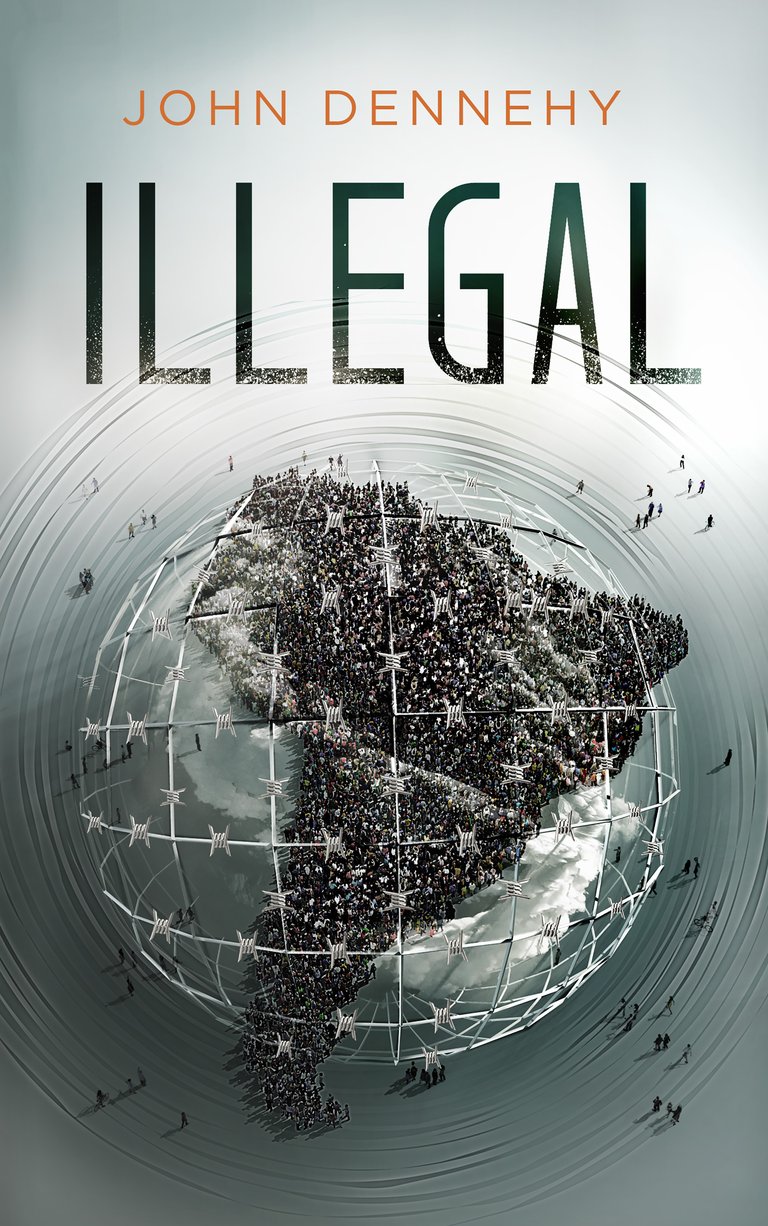

I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the twenty-first installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5 | Ch 6 | Ch 7 | Ch 8 | Ch 9 | Ch 10 | Ch 11 | Ch 12 | Ch 13 | Ch 14 | Ch 15 | Ch 16 | Ch 17 | Ch 18 | Ch 19 | Ch 20] and every few days I'll post another chapter. From the back cover:

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

--

Just Another Gringo in Colombia [Chapter Twenty-One]

I spent the next week in New York celebrating Thanksgiving with family and seeing old friends. My parents always host Thanksgiving and around two dozen guests, from both sides of the family, came to dinner. Every year my dad made a special vegetarian stuffing that I loved and my mom made a green bean casserole with caramelized onions baked on top. Plus, there were boiled parsnips and mashed turnips and lots of other dishes that I only ever had once a year. The table overflowed with homemade dishes others had brought as well. I always put everything together on my plate, topped it with cranberry sauce and mixed it into a multi-colored mush. We all ate until our stomachs felt like bursting.

Thanksgiving has always been my favorite holiday. There are no gifts or consumerism, just family eating together and appreciating what they have. And leftovers.

The next day, after everyone had left I ate another grand meal with just my parents. My dad fried up mashed potatoes and mixed in some corn and stuffing until it was all a golden brown. My mom took out plates and opened a bottle of ketchup. Everyone scooped up a serving onto their plate and we all sat down.

“Are you ready to say prayers?” My mom asked my father.

In unison, my parents made the sign of the cross and began to pray. I sat silently with my hands on my lap. I was raised Catholic but had moved away from religion toward agnosticism after I left for college. My parents were still devout believers though. When they finished we all ate together.

On my last night, rather than waking up early, I never went to sleep, relishing my final hours in the states before hugging my mom goodbye and setting off with my dad for the airport. We arrived early so I had plenty of time to sit and talk with him. “I wish to God you would come home more often,” he said.

The previous time I had flown to South America was the first time it was difficult to say goodbye—the first time that the airport symbolized separation rather than just excitement. I began to understand why, per data from the United Nations, only 2% to 3% of the global population lives in a country they were not born in.

My previous flight represented the first time I wasn’t just going away on another trip only to someday soon return “home.” For the first time, New York had become the trip and Ecuador the home. These words were never spoken, but they sliced through the heavy air that hung between my family and me.

That night I arrived in Bogotá. I was legal in Colombia so there was no reason to worry, yet waiting in line, passport in hand, I surely did not feel relaxed. My passport was quickly filling up with Colombian and Ecuadorian stamps, including one announcing to the world that I had been deported. Furthermore, I was entering Colombia for the purpose of illegally leaving it. Immigration always made me nervous now.

I made it through with no problems, but with only sixty days rather than the ninety I was hoping for. An arbitrary decision made by an unknowing officer that would have great effect on me. I was hoping to put off my next border crossing for as long as possible, so I’d have to apply for an extension before I left the capital.

A taxista took me to a hotel tucked away on a side street and walked inside with me. The middle-aged couple stood stiffly behind the desk, though they gave a quick nod to the taxista. The man wore a sweater over a collared shirt and parted his hair neatly on the right side; the woman wore a conservative dress and just enough makeup to notice.

“¿Cuanto cuesta una noche?—How much does one night cost?” I asked

They responded in heavily accented English. “Sixty thousand. That means $30 for you.”

I was tired and responded in English. “That’s too much. It’s already late and I will be leaving early. It should be 20,000 or at most 25,000.” I took out a wad of pesos from my pocket and reached my hand out. “I can do 30,000.”

The couple stood smugly and took the bills. “The cost is 60,000, you can pay me the other half in the morning,” the man said.

“That’s too much. Give me back the money and I’ll look somewhere else,” I said. I was exhausted but knew that the couple was ripping me off. Some hotels attempted to double the price for foreigners but usually backed down if you challenged them.

“50,000,” he said.

I paid him and went to sleep in my room. When arriving to a foreign city by plane I had come to accept that my first night would be a gross rip-off—nonetheless I slept well on my hard bed and woke up refreshed. The owners of the hotel spoke poor English and probably assumed I was just another gringo.

Gringo is a term used to describe people from the United States in Latin America, though it is also often used to group together all Westerners. The origin is disputed but the most common story I heard in Ecuador dates it to the Mexican-American war when U.S. soldiers occupying Mexico wore green uniforms. Mexicans would shout “green go!” at the soldiers, which evolved into ‘gringo.’ Truth is, most people have no idea where it came from and now just use it to group together all the white faces in this foreign land. Latinos that live abroad are sometimes mockingly called ‘gringo’ when they return to their native country, therefore an accurate modern translation can be ‘outsider’ or ‘foreigner.’ Most ‘gringos’ seemed to embrace the term, or at the very least found it convenient. I never did. A lot of backpackers and expats in South America stuck to a rather narrow trail—often called by those who travel it, The Gringo Trail. They went to the same bars, the same restaurants and the same hidden away mountainside towns where people spoke English and sold Budweiser. I never enjoyed being grouped in with anyone, especially not with people who adhered to the very same culture I was trying hard to leave behind.

When I left to walk around the city, the hotel owners asked me for 10,000 more pesos; I said no and kept walking. I went out hunting for information: cheaper nearby hotels, where to get my visa extended, and transportation to the border. My mission didn’t go so well and I ended up just writing an email to my parents and using a pay phone to call Lucía to let everyone know I made it into Colombia without incident. Though by now I had an Ecuadorian cell phone, I never brought it with me on these trips. It didn’t fit the character I was playing and would ruin my ‘stupid tourist’ cover if the police found it during a crossing. When I returned to my hotel, I decided that I would move to a new room in el centro because it was rather residential where I was currently staying.

When I returned to the hotel, the owners were outside in a car and offered to drive me to the visa office, as they were heading that way on an errand. “Of course, you will have to pay us,” the man said. I refused. Typically, South Americans are astonishingly friendly and generous people so I hated it when that transformed into greed at the sight of a white face. From the beginning I sensed they saw a dollar sign where I stood rather than a person. When asked again, I swallowed my pride and took them up on their offer, knowing it was my quickest and easiest option.

On the ride we struck up some basic conversation, but it dragged because their English was rather poor and it was clear neither party was genuinely interested in the other.

“What do you do?” the man asked.

“I teach English in Ecuador.”

He looked back at me, surprised, and asked, now in his language, “So you speak Spanish?”

“Sí.”

“How long have you lived there?” he asked.

“I lived in Cuenca, a city in the south, for a few months, but I have been living in a small city near the capital called Latacunga for over a year now.”

“So you work for a program from North America or maybe you are in the Peace Corps?”

“No, I work independently. I came to Ecuador for the first time about two years ago and I liked it so much I just never left. I started teaching English at first because it was the only job available to me, but now I love doing it.”

They were clearly impressed with these revelations.

“What is it that you like about Ecuador so much?”

“I like a lot of things. It’s so different from where I am from in New York. Where I grew up seems so selfish and self-centered compared to here. Here people have so little, but they share all they have, while there people have so much and give so little.” I told them I also liked the stronger sense of community. “Life is simpler here, and for me, I think it’s better.”

“Do you have a girlfriend in Ecuador?”

With a wide grin on my face, “Yes, I’m on my way back to her right now.”

Our excited dialogue continued as the driver bought a round of ice pops for the car from a street vendor in traffic, and we inched closer to our destination. Over the course of the ride their attitudes did a one-eighty, and by the time they dropped me off, they refused my money with a smile before wishing me luck. Though I was certainly happy to shatter their preconceptions, the incident illustrated a larger, less pleasant point.

I had lived my whole life in places where I was in the racial majority. Ecuador was the first place I had been where people so explicitly judged me by how I looked or where I was from. I hated it. The truth is, people treated me better more often than they treated me worse; still, it always made me angry and uncomfortable.

It helped put things into perspective for me. I was upset by the principle of people treating me differently based on some superficial attribute, but charging an extra dollar for lunch is one of the least threatening ways to be discriminated against. In the suburbs of New York City where I grew up, groups of teenagers would sometimes beat up immigrants for fun. While I was living in Latacunga, I heard news reports of a particularly disturbing incident that took place in New York. A young Ecuadorian man, chosen at random and called ‘a dirty Mexican’ by his teenage attackers, was beaten to death a ten-minute drive from my childhood home.

This post has received a 62.50% upvote from Thunder Vote!

amazing story

nos seguimos?

You got a 36.62% upvote from @upmewhale courtesy of @johndennehy!

Earn 100% earning payout by delegating SP to @upmewhale. Visit http://www.upmewhale.com for details!

This post has received a 15.00% upvote from @teevmoore!

You got a 40.00% upvote from @booster courtesy of @johndennehy!

NEW FEATURE:

Quick Delegation: 1000| 2500 | 5000 | 10000 | 20000 | 50000You can earn a passive income from our service by delegating your stake in SteemPower to @booster. We'll be sharing 100% Liquid tokens automatically between all our delegators every time a wallet has accumulated 1K STEEM or SBD.

This post has receive a 25.00% upvote from Coyote Bot.

Hi @johndennehy!

Your UA account score is currently 2.501 which ranks you at #16233 across all Steem accounts.

Your rank has improved 36 places in the last three days (old rank 16269).Your post was upvoted by @steem-ua, new Steem dApp, using UserAuthority for algorithmic post curation!

In our last Algorithmic Curation Round, consisting of 219 contributions, your post is ranked at #197.

Evaluation of your UA score:

Feel free to join our @steem-ua Discord server

Your post was mentioned in the Steemit Hit Parade in the following category:Congratulations @johndennehy!

It's interesting what you say about "having always lived in a place where I was the racial majority". Made me think about the fact that in the past ten fifteen years I have been living in places where I was the racial minority. Sometimes I zoom out of the picture and I see this, sometimes I see it in other people's eyes, but most of the time I don't even realize I am a minority. Maybe because it remains a strong minority (I belong to the so-called "white" group). But then thinking about it, in my home country Italy although I look like the majority, ethnically and culturally speaking I have always belonged to a minority (jew - atheist family against the so-called catholic majority). But then...how could you be part of the majority in New York, where the majority is of mixed origins?

I suppose I only realized it because it was a change.

Good point about New York, though that's New York City. I had previously lived in New York State and the NYC suburbs (Long Island) which was majority-white as well as Hartford, CT which while fairly diverse was also majority-white.

This post has received an upvote from YaYa Bot!