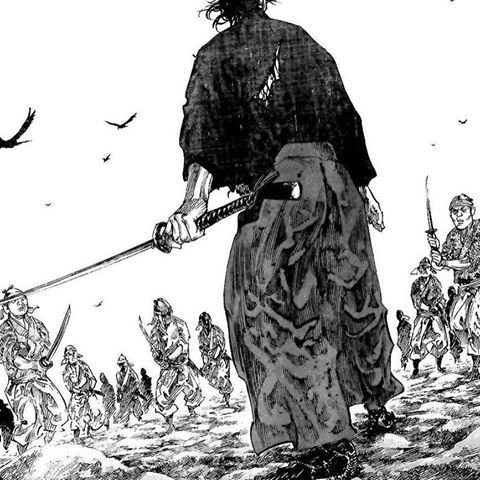

Everywhere he goes people whisper his name with fear and reverence. Bandits are either terrified of him or conspire to kill him. He walks with a palpable aura--either of carnage or of peace. And whenever he draws his sword, he leaves broken and bloodied bodies in his wake.

Miyamoto Musashi takes on the Yoshioka School in the manga Vagabond. Spoiler: he wins.

Martial arts exponents are a staple of most genre fiction. From Chinese wuxia to Western high fantasy, sword & sorcery to steampunk, if the story justifies it, a martial hero or villain will appear. He wears an aura of supreme confidence, and woe betide anyone who stands in his way. His presence alone guarantees spectacular action scenes.

Unfortunately, most people have no idea how to write one.

To be clear, this article is aimed at writers who want to authentically portray trained martial artists in their stories. This applies to stories whose aesthetic favours the realistic portrayal of martial arts. Here, characters who properly apply martial principles survive battles, and those who are less skilled fall by the wayside or into shallow graves. In such a setting, their skills may be augmented by magic or superscience or some other justification, but this augmentation does not take the place of skill.

Why would you want to write stories like this? Readers are already used to portrayals of martial arts that are more grounded in fantasy than reality, in flashy visuals rather than gritty realism. It's easy to just cook up a showy fight scene and move on. Why spend the time and energy to choreograph a realistic fight scene?

I do it because I'm a contrarian who grew up reading thrillers, and I get bored when I see unrealistic action scenes. Less flippantly, a realistic fight scene would reinforce the aesthetic of a story that is meant to carry the weight of reality. The gritty feel of action movies like Taken and the Bourne series come in no small part from the way the characters move, think and act in combat, reinforcing the notion that the protagonists are truly highly-trained operatives. Furthermore, a fight scene that respects martial applications demonstrates the true power and grace of the human body, a kind of beauty that can manifest in the real world outside of the screen or the page. Done right, it is so awesome it inspires people to seek training and build up their bodies.

It's Not (All) About Speed, Strength, Size or Fancy Techniques

Tiny girls, huge swords, not quite what we're looking for.

When described in fiction, martial experts tend to fall into two not mutually exclusive categories: superstrength or superfast.

In the first category we have characters who rely heavily, if not exclusively, on physical might. Conan the Cimmerian is described as 'steel-thawed' and as primal as a wolf, with sword by his sword and magnificent musculature on display. Guts from Berserk carries a stupendously long and heavy sword, and is seen cleaving armored enemies in twain. Such characters are shown accomplishing incredible feats of strength, all the more impressive if they are merely mortal. More often than not, these characters tower over everyone else, emphasising their strength.

In the second we have characters who are incredibly fast and/or agile. Himura Kenshin is the most famous Japanese example, being able to accelerate and strike so quickly no one sees him coming. Yoda appears tiny and elderly, but he is deceptively acrobatic. These characters impress the audience by acting much faster than the average human.

At the intersection of both categories, we have characters noted for their special skills, which are usually flashy named moves. Himura Kenshin's ultimate technique is an attack so fast it appears to strike all nine key targets on the body at once. In wuxia stories with heavy fantasy elements, heroes and villains routinely execute special techniques that grant them supernatural speed or strength. These techniques come to define the character, and the appearance of an ultimate technique signals the desperation of the moment.

In a realistic fight scene, none of these elements are paramount.

Prodigious size and strength are useful, if you live long enough to employ them.

This is not to say that strength, size or speed don't matter. They do. Mere mortals are not going win a grappling match with a three-hundred-pound sumo wrestler, or go toe-to-toe with Jack Dempsey in the ring at his prime. However, true mastery of martial arts allows the practitioner to at least partially negate these elements through applied skill. Being strong and fast and resilient is useful, and indeed necessary for the kind of physical work that martial heroes find themselves doing, but they don't always decide the outcome of a battle.

As for flashy techniques, it is my experience, and the experience of those more experienced than me, that flashiness equals death. For the user. Sure, they can be fun to perform, and they may even work against rank amateurs, but the more complex a technique is, the more likely it will fail under a life or death situation. And that's not even counting techniques that violate the laws of reality (see Himura's ultimate technique).

Mastery of the Fundamentals

Kenji from the eponymous manga shows us how it's done

In my previous post on martial mastery, I described how mastery of the martial arts comes from mastery of fundamental skills. In my opinion, many creators ascribe to the physical what they should instead ascribe to skill.

The perception of superstrength comes from perfection of body dynamics. You can be the strongest person in the world, but if you don't know how to punch, you'll just hurt yourself. People with an innate understanding of how their bodies work will be able to transfer their entire bodyweight into the target, allowing them to defeat seemingly larger and stronger opponents. In addition, people who can move efficiently have no wasted movements, allowing them to move faster than those who can't fully control their bodies.

The perception of superspeed comes from the understanding and application of footwork to control range. If you control the range between yourself and the opponent, you control the speed of the action. Counterattacks in the martial arts tend to involve stepping towards the enemy--in addition to adding momentum to the blow, you are also reducing the range to your target, which makes you look faster. Likewise, using deceptive footwork and body language, you can create a false perception of the distance between you and the enemy, allowing you to seemingly move faster than he can react. Stepping to the side maintains the range but changes the angle between you and the enemy, and a large enough side step may carry you out of an enemy's cone of vision, effectively making you disappear to his eyes. Stepping backwards is usually contraindicated since a human can move faster forwards than back, but if weapons are in play it is one method of sniping at an opponent's hands without getting struck yourself.

Proper timing creates the perception of speed and invincibility. A person with proper understanding of timing knows just when to move, allowing him to block an attack, strike at an opening, evade a counter. Such a person seems to have an impregnable defense and unstoppable offense. He doesn't need to be strong or fast; or just needs to know where to move and when to defeat you.

Dojos and martial arts schools break out fancy techniques mainly as a means to attract and retain students. For combat applications, instead of flashy techniques, strive for what Rory Miller calls 'Golden Moves'. These should do four things: put you in a better position, put the enemy in a worse position, defend yourself from the enemy, and dump power into him. For example, in FMA, a response against a downward slash is to step out with a rising cut. By moving to the outside, you have evaded the enemy's attack and put yourself in a position where you can flank him. The enemy, in turn, can't attack you without turning, buying you time to react. If your timing is poor, the rising cut deflects the enemy's blade, and now you are at the right angle to pin the enemy's arm and deliver a finishing stroke. If your timing is good, you'll cut off his hand or arm. With excellent timing, you'll slice right through his torso. Such techniques are easy to remember and pull off, are grounded in reality, are still accomplish the same goal as a flashy technique -- that is, to finish the fight.

Every martial art is built upon certain assumptions and principles of movement. Kali is based on weapons, and practitioners move as though weapons are always in play. Boxers focus on punches, footwork, timing, slipping, blocks and footwork, usually with gloves on. Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu has a powerful ground game. Every master has an inherent understanding of these principles of movement, as well as the above-mentioned skills, allowing them to perfectly execute their favourite techniques.

Going beyond mastery of the principles, martial masters control the fight. They won't fight someone else's game; instead, they use their skills to force the opponent to fight their game. For example, against a boxer, our master may use long-range kicks or shoot in for a throw. When facing a grappler, he'll keep out of grappling range and wear him down with strikes. If the stakes are high enough and it's a life or death situation, he won't even go for a stand-up fight. He'll call friends, bring tools, and use deception and the environment to get in close enough to unleash his skills without risking the chance of a counterattack.

Reference Materials

Kamishiro Yuu gets his game face on in Holyland

This article is just a primer. I do not claim to be a master, only that I have studied under them. If you want to delve deeper into the subject, you need to do your research.

The ideal is to study a martial art and pay close attention to acknowledged masters of the art. Even if you don't or can't attend classes, you can find plenty of books and videos. Look at how these masters move. Observe the totality of their bodies, starting with their feet and working your way up, and seek the principles they employ. Look first at the universal skills -- body mechanics, range, footwork, timing -- then look at the skills specific to the art.

If you want to dive deeper, you need to develop the vocabulary to understand and describe what you're looking at and for, and the effects of violence on characters. Rory Miller's Violence: A Writer's Guide and Marc MacYoung's Writing Violence series are excellent primers aimed at writers. NRA Freestyle Media Lab examines action scenes in popular movies and breaks them down from a self-defence perspective, while Nerd Martial Arts and Martial Gamer examine techniques in martial arts.

Once armed with the basics, you have the foundations for additional research.

Done properly, though, violence is boring. If your character can reliably end the fight in one move, it's not particularly exciting for your audience. To write exciting fight scenes, look also at how creators choreograph them. For movies, I recommend Taken (the original!), The Raid and The Raid 2, the Bourne series, and the Rorouni Kenshin live action film trilogy. In written fiction, look up John Donohue's Sensei series for Japanese martial arts, Dashiell Hammett's Nightmare Town for Western stick fighting, and Marcus Wynne's novels to examine modern combatives. For manga, there areVagabond, Ookami no Kuchi: Wulfsmund, Kenji and Holyland. Anime has Junketsu no Maria and its authentic portrayal of Historical European Martial Arts while Cowboy Bebop has stylised depictions of Jeet Kune Do.

Fight scenes, authentically and excitingly portrayed, make stories stronger and show the reader what a trained human can truly do. If you want to do more than rely on the same tropes of superstrength, superspeed and flashy techniques, seek out the fighting arts of the world and see how you can apply them to your own work.

Of course, I would be remiss if I didn't point out that my own novel, NO GODS, ONLY DAIMONS features an exacting portrayal of Filipino and Historical European Martial Arts. You can find it on the Amazon Kindle store and the Castalia House ebook store. It is also eligible for the Dragon Awards; please vote for it under the Alternate History category. Thanks!

Never realized how prevalent the martial hero was across genres! My most recent favorite was Chirrut Imwe in Rogue One. The blind martial hero is an especially powerful character, always seeming to turn their handicap into an advantage.

Thanks for the post!

You're welcome!

Upvoted and RESTEEMED :]

Thanks!

Interesting. A really nice text and I agree with your point. One thing I would like to add is that like movie fighting is different from real fighting I think fighting in books need to be slightly different from real fighting as well. I heard this quote that i really like which says it concisely : in a stagefight everybody needs to be able to see whats going on and noone should get hurt. in a real fight noone should be able to see whats going on and at least one person needs to get hurt. However while the stagefighting is very different and must follow cinematic reality, fighting in books dont need that as much so potentially you can get much more realistic fighting in a text. I think it is important to focus on realism, simply because it makes for better fightscenes, but it should (in my opinion) be subordinated the storytelling

Indeed. Different media will have different requirements. I'd say that static visual media like manga and comics fall in between movies (and games) and written text: the reader should still be able to see what's going on, but he can study the scene at leisure.

Sotrytelling should come first, though I approach fight scenes as an integral part of the story. Then again, I write the kind of stories that demand realistic fight scenes. Stories from other genres, such as slapstick comedy, are going to demand a very different approach to fight scenes, and the fight scenes should be tailored accordingly.