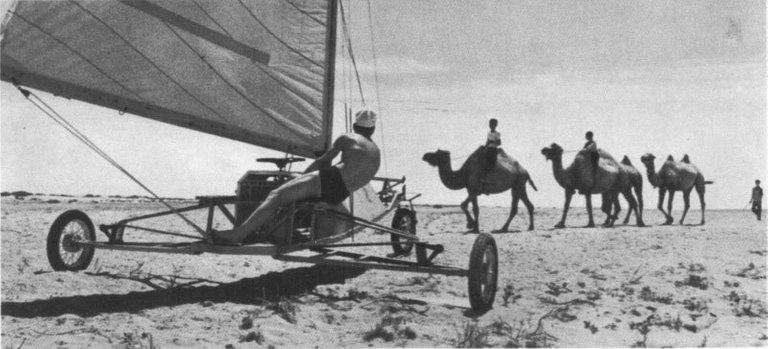

One evening in June some shepherds in the Kara Kum Desert near the Aral Sea saw a strange sight. Three white sails floated over the sand along the far horizon. The hot, shimmering air of the desert will often conjure up a mirage, and so the shepherds awakened old Asan Bakhmyrzayev, who was asleep in his tent.

"Is that a mirage?"

The old man peered intently into the distance, then rubbed his eyes with a square of cotton. "No, it's not a mirage," he said at last.

News spreads quickly in the desert. The next day the word was: "Three strange fellows from Moscow are crossing the desert in carts with sails on them."

I first heard of the sails and wheels last summer. "You must be crazy," I said when I learned of the venture. "You've probably forgotten this is the desert."

"So what?" Edward Nazarov replied. "So this time it's the desert."

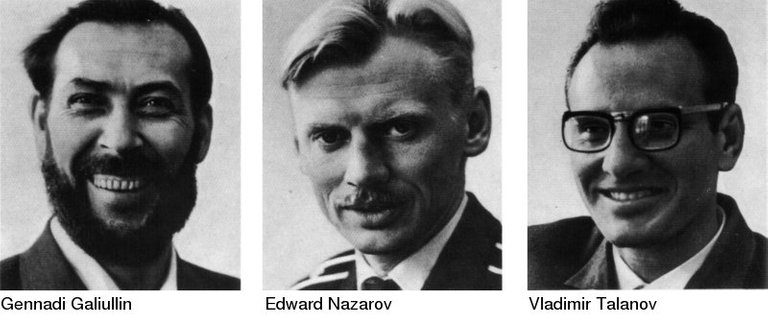

I had nothing to say, because I've known him for a long time. He was a navigator on a submarine and then became an engineer. Edward had tramped all through the Far North with a pack on his back and had crossed the Aral Sea in a small foldboat with a sail. We became friends on the Kamchatka Peninsula. He had come there with the idea of scaling a few volcanoes, as he put it. We scaled one of them together, camping at the top for eight days in a snowbound tent, but Captain Nazarov felt one volcano wasn't enough. He again flew to the Kamchatka during his next annual vacation. The telegram he sent me read: "Saw the Earth from Mt. Klyuchevskaya." He certainly stood to be congratulated, since only about four dozen people in the entire country could have said the same.

There were four of them on this jaunt across the desert. The other three were Vladimir Talanov, an engineer and expert yachtsman, Gennady Galiullin, a hiking instructor, and Lieutenant-Colo-nel Igor Sysoyev, as devoted an explorer as the others, the cameraman and guitarist of the group.

"If you intend to go yachting, you ot least have to have a yacht."

"We'll make our own."

"You really are crazy," I said, but now there was a shade of understanding in my voice.

Anyone who has tried to make as little as a good handle for a hammer by himself will understand the job they were undertaking. It called for experience in designing to construct a cart that could be driven without a motor. They also had to be blacksmiths, fitters, welders, lathe-operators, carpenters and riggers.

"You're all crazy," I said fondly when I saw their grasshopper-like carts.

I told them I would very much like to be present when they started on their journey.

After the dismantled sailing carts, equipment and supplies were loaded onto a flatcar we parted, to meet in a week's time on the shore of the Aral Sea.

That same evening I went through the files at the editorial offices and found a French magazine that proved there were quite a number of crazy people on earth. Brigadier General Du Busse wrote of crossing the Sahara Desert in a sailboat on wheels. The general headed a group which was made up of French, English, American and Belgian enthusiasts. The staggering velocity of the desert winds took them across three thousand kilometers in thirty-two days. Their caravan had an escort of supply trucks and two light planes, and General Du Busse was in contact by radio with the military garrisons stationed in the desert. However, only eight of the original twenty sailing carts completed the journey. As I read the details of the journey I realized that our humble foursome, lacking trucks, planes and radio communication, could only serve as a first scouting expedition into the desert.

Upon reaching our place of rendezvous I spotted a red and a blue tent, three white sails and four sunburned, peeling men.

After we had embraced, drained a bottle of Armenian cognac and tossed it far onto a dune, I had my first-good look at the camp. This week of living in the desert had been part of their plan. It would give them a chance to become accustomed to the sun and a new type of diet and to check every last detail of the carts.

When a person stops in a place for any length of time, no matter if it happens to be in a desert, he soon finds he has acquired a small menagerie. A hairy tarantula had taken up residence in an empty bean can at the entrance to one of the tents. For some reason or other it had been named Frol. Two hedgehogs with pointed ears were settled in a basket. A kitten named Keshka romped nearby, while a large and very solemn turtle meandered back and forth on a long nylon leash in the middle of the camp.

Everything was ready for the sailing day. Everything save the most important factor: there was no wind. They could not even stage a trial run. The three sails hung limply from the masts.

Another day passed, and then another. Still, there was no wind. We could only sigh and try to find something take up our time. I would go off into the sands to take pictures, Edward pottered about the carts with a hammer and drill. Gennady busied himself cleaning the carp a curious, deaf-mute fisherman brought us each morning. Igor strummed his guitar. Volodya Talanov, the captain of the expedition, decided to repack the cellophane bags of provisions.

"What's this? Milk?" he asked Gennady.

"No. I think it's cabbage."

The white powder turned out to be "stuffed cabbage and noodles". The Institute of Processed Foods had supplied the men with a new type of food, having made them promise faithfully to note the intake and to weigh themselves regularly. During the first week the dehydrated provisions were supplemented by fresh Aral carp. Still, the total weight loss for the expedition was over sixteen kilos at the end of the journey.

In the evenings we gathered around a campfire, using the small balls supplied by local camels for fuel. When the sounds of Igor's guitar died away we could hear the whisperings and rustlings of the desert, for the sands that were asleep and silent all day long awakened the moment the sun dipped into the sea. Sounds of the mysterious world coming to life around us reached our fire.

Large, friendly stars hung over the desert. A light sailed along the horizon. It was an automobile. Another light was moving in from the sea. This was a fishing launch returning to Aralsk. The red tail lights in the sky belonged to a plane from Tashkent. All the motorized wonders of the century were putting in an appearance. Everything was in motion. We alone sat by the shore like ancient mariners, waiting for a fair wind.

It was blowing up! A brisk northwester was blowing! We broke camp in ten minutes flat, packed the nylon water casks, provisions and our sleeping bags into the baggage compartments of the carts. Volodya's sail filled out. A moment's negligence on his part and the sailing cart showed us its mettle. It was off all by itself, racing towards the far dunes without its skipper. I can vouch that our captain never ran so fast in his life. He finally managed to catch up with it. He beamed, because he had caught it and because the three-wheeled wonder was capable of such speed.

Soon three white sails unfurled. I felt that if the angle were changed but a bit we would be off. Indeed, we were! We were under way! It was a feeling a parachute jumper would recognize, being similar to having a chute billow out overhead. They say that some jumpers actually sing at this moment. We all began to yell excitedly. The aluminum mast of our long-nosed cart creaked, the crusted sand crunched and sank under the wheels as a bird chirped monotonously nearby. We all felt light-headed. Igor and I whisked the dust off our camera lenses as we raced on foot towards the dunes to get a side view of the billowing sails. They were beautiful! Each driver had one hand on the wheel and the other on the rope. Their peeling faces were radiant. True, their speed could have been greater, but the carts were heavily laden and the wind was not that strong. Still and all, we did cover about seventeen to twenty kilometers an hour. Our course lay over flat, hard-packed sand, bumpy, saksaul-covered dunes and weeping salt-marshes. Any vehicle would have gotten stranded here, but all we left were three shallow rows of tracks on the boggy, salty soil. However, it was no pleasure to bump over the hummocks. The aluminum rods creaked dangerously. In some spots our winged carts behaved like prancing steeds that might suddenly sprain a leg and tumble over. Despite our many worries, we still managed to observe the large lizards perched like birds on the bushes, the Saigak antelope racing across our path and gophers darting into their burrows.

We covered fifty kilometers in three hours and could not hope for more the first time out. However, at sunset we found ourselves in a sand trap. We had to drag the carts, one at a time, over the thistle-covered hills for more than a kilometer and finally pitched our tents in the dark, then went gathering "camel fuel" for a campfire with the aid of our flashlights. After a meal of powdered meat and cabbage and noodles and a count of our bruises and bumps we settled down for the night.

The journey had begun. The following morning might have pleased anyone but us. It was a cool and sunny day. Two dozen camels, overcome by curiosity, were jostling each other near the tents. A gopher whistled. A yellow bird perched on one of the masts and also whistled. We whistled, too, but sadly, for the fair wind had changed during the night to a head wind. After breakfast we drew various possible routes in the sand with a stick, discussed the situation and finally concluded that: 1. We would have to adapt our course to the wind; 2. We would have to unload as much weight as possible to see if the carts could sail across the dunes. This was a great disappointment to Igor and me, for when everything was totalled up we saw that the equipment and emergency rations would have to be ditched, as would the two passengers. However, there was no other way out. We had a last cup of tea together, sang a last song and I took a last picture of the three men waiting for a fair wind. Igor and I packed our knapsacks, embraced the others and set off to search for the Aralsk-Bugun road which trucks occasionally traversed. The three skippers were heading for Bugun, the next stop on their itinerary. From there they would proceed to Nukus and on across the Kara Kum Desert to Krasnovodsk. That was the ideal route. They also had a reserve one. When they reached Bugun they would decide which to follow.

Man is so made that there must come a day when as a child and for the first time, overcoming his fear, he crosses a dark room by himself, swims a river, spends the night alone in a forest, and, later, climbs a mountain, sails across an ocean, pilots a spaceship into the unknown or starts off across a desert in a winged cart.

Such were my thoughts as I returned to my desk and waited for news. Five days later I received the following telegram:

"Northwester took us across the dunes to Bugun. Everything fine. We're tightening the riggings, heading for Kazalinsk, Kzyl Orda. (Signed) Talanov, Nazarov, Galiullin."

A month later the adventurers were in Moscow. They were nut-brown from the sun, much thinner and, I believe, content. Naturally, I showered them with questions.

"Tell me all about it."

"WelI, we completed the course, covering about a thousand kilometers, counting the detours, in a month. But don't think we were constantly on the go, because we spent most of the time waiting for a fair wind and only averaged about twenty kilometers an hour. There were times when we just crawled along and others, on flat, packed sand, when we averaged eighty kilometers an hour. It was a wonderful sensation."

"Did you have any trouble?"

"We had to stop for repairs in Bugun, and you know repairs on the road are nothing to get excited about. Besides, there was the heat, 42° C, which is no fun, not even when you're in the water, but all we had was scorching sand. Drinking water was no problem, though it was always hot and had an awful taste. We tried the ancient method of improving the taste by putting a silver spoon in each cask. At one time we ran out of food for two days and had to trap turtles."

"How about the rations the Institute gave you?"

"They were edible. If you want to know, though, the best and most reliable item we had was the time-honored soldiers' hardtack."

"Did you encounter any people in the desert?"

"Mostly shepherds. They treated us to camel's milk and wanted to get a good look at the carts. Sometimes they teased us, asking how much we were paid for that kind of work."

"Did all three craft reach Kzyl Orda safely?"

"No. When we were going about fifty kilometers an hour, one of the carts keeled over, bending the mast so badly it made the cart look like a plane wreck. The skipper wasn't hurt, though he did fly through the air some five meters before landing in the sand. That was about the middle of the course."

"What was the most difficult stretch?"

"Probably the run along Lake Kamyshlybash. It's full of hummocks and dunes. But we were rewarded for our trials, because we never saw a lake like it before."

"Oh, I forgot to ask about Keshka."

"He was with us till the very last day. We really got used to each other. At night, when we'd spread one sail on the sand and cover ourselves with another and go to sleep, Keshka would go off hunting. There were small lizards all over the place. He really stuffed himself. But he suffered from the heat and would plop down by the mast more dead than alive. He disappeared when we got to the hotel in Kzyl Orda. Someone must have picked him up. Maybe he wasn't a born adventurer after all and left us the moment he sniffed a cozy, settled life."

"One last question. Are you satisfied with the results of your trip ?"

"Yes. Very much so."

This is what these crazy fellows are like.

What a story! Welcome back @peskov. Thanks for sharing another one of Vasily's journals.