When sending a letter to the large southern city of Rostov one always writes "Rostov-on-Don" on the envelope, knowing that there is another Rostov some-wheres. Indeed, there is. Not everyone is aware that the huge southern metropolis of Rostov is but a babe-in-arms compared to the little northern town of Rostov.

This town was 900 years old when the first log house of the second Rostov was built near the mouth of the Don River in the south. Moscow was a village at a time when Rostov was never referred to by any other name than Rostov the Great, for it was as famous as Kiev and Novgorod then. Rostov was first mentioned in the Chronicles for 862 A.D., one thousand one hundred and twelve years ago. Let us try to imagine this huge slice of time by counting as many years forward instead of back. New cities are going up each year. Let us imagine the modern cities of Dubna or Angarsk in the year 3074. Which of the science-fiction writers will venture to say what the world will be like then? This is what a thousand years means. Rostov has weathered this slice of time. That is why we look upon it with undisguised awe, as if it were a ship that has arrived from a land known to historians as Ancient Rus.

I have been to Rostov many times, both on business and simply when I felt the bustle of modern life closing in on me. Each time I began to feel its presence while still on my way.

The road from Moscow to Yaroslavl is as ancient as these two cities and as all the small towns, villages, churches and monasteries strung along it like rare pearls on a stout thread.

Far from being relegated to the past, this ancient road is now a busy highway. Here, side by side with another age, are bright service stations, concrete bridges, glassed-in cafes and a never-ending stream of trucks and excursion buses.

One can never doze off while travelling along this highway. In one place it seems that the stream of traffic in front of you will run smack into a pink church that stands proudly and stubbornly in the middle of the road. However, cars and trucks that are used to zooming straight ahead curve around it. There it stands, to be marvelled at from all sides, while the bearded deity painted on its wall coexists amiably with the figure of a young militia man on a nearby traffic poster.

Meanwhile, another belltower has come into sight amidst the glowing clouds of twilight. The road stretches on through quiet groves filled with the green mist of spring. When passing here I am always reminded of Roerich's canvases. Here are the round hills, the strips of fields between islands of woods and, farther on, billowing hills and valleys and a placid lake fringed by bushes. If one glimpses a white horse hereabouts, no matter that it may be rubbing its side against a telegraph pole, it will still seem to be the legendary horse of Alyosha Popovich of yore, for the epic tale holds that the hero came from a village near Rostov.

Meanwhile, the road has yet another surprise in store. The belltower that was silhouetted against the clouds gives way to a cluster of silver, gold and gold-starred blue cupolas. All this comes rushing at you from behind a rise. By then your car has entered a town as festive as a marketplace. In the center is a fortresslike wall somewhat lower than the wall of the Moscow Kremlin. Beyond it is a breathtaking conglomeration of churches, belltowers, chapels and towers, some of great splendor and magnificence, others quite simple and unprepossessing. A tall, imposing monk dressed in a black sutane with a tall black brimless hat with a veil hanging down behind passed by carrying some books under his arm. His wide sleeve flapped in time to his hurried steps. The entire area between the churches was filled with old women and sightseers. The women were obviously pilgrims. Some sat about wearily on the churchporch, drinking milk right out of milk bottles and breaking off chunks of homebaked bread. As others passed the church they crossed themselves and stopped to kiss the stone beneath the darkened icon of St. Sergius. There is a hollow in the stone from having been kissed so many times. Five years ago I never suspected one could see such a sight in modern times.

A few steps outside the gates and you once again rejoin the everyday world of film posters, trucks carrying shiny new motors from Yaroslavl and girls in miniskirts. Life rolls on past Zagorsk Monastery.

The heart of the Russian Orthodox Church, located within its kremlin walls, does not in any way affect the ancient town's modern way of life. There was good reason for establishing the Church's headquarters here. In the long-forgotten past, Zagorsk had its beginnings in the hermit Sergius' hut, which stood alone here in the forest wilds. The Church was only too glad to sanctify a man like him. In time, a monastery was built in the woods on the site of his hut. The tsars of Muscovy stopped by here on their pilgrimages to Rostov, to atone for their sins and ask for God's assistance in their wars and affairs of state. Dmitry Donskoi journeyed here to give thanks after defeating the Tatars. Peter the Great came galloping up to the monastery along the Rostov Road, seeking refuge behind its walls during Sophia's plot to assassinate him.

The tsars lavished money from the Treasury upon the monastery, which was to become one of the most wealthy and powerful in all of Russia. New buildings and chapels were forever going up within the brick enclosure to produce, finally, a veritable collection of radiant churches.

Zagorsk, a town as cozy and bright as a patchwork quilt, is one of three ancient settlements on the Yaroslavl Road. The other two are Pereslavl-Zalessky and Rostov. The three are evenly spaced at distances of seventy, miles, which was once a day's journey by horse. Nowadays, Pereslavl is an hour's drive from Zagorsk. Gorinsky Monastery, an impenetrable fortress on a hill to the right of the road, stands guard over the blossoming, green town. Small houses and trees edge the little Trubezh River, whose winding banks have never been citified. In summer the surface is dotted with water-lillies and a great profusion of rowboats. It seems as if every inhabitant owns one. Little wooden platforms the women use for rinsing clothes protrude into the water.

Pereslavl was built after Rostov, but its past, too, is like a deep canyon. Alexander Nevsky, one of Russia's finest sons, was born here in 1220 and was baptized in the church that (unbelievably!) has been spared by time and still stands by the road. Its single helmet-like cupola is no higher than the treetops. This is indeed a gem in white stone. The uncluttered lines, the fine arches and its absolute simplicity present art in its purest form. The church, which is 800 years old, is one of Russia's priceless treasures.

Like Zagorsk, Pereslavl invites you to linger on. Even a short stopover will take you to Lake Pleshcheyevo, where Peter I played with his fleet as a boy. The one surviving yawl is on display in a special pavillion at the lake's edge.

Mikhail Prishvin, the writer, lived here. If you leaf through Nature's Calendar, one of his wonderful books, you will find a story about Peter's yawl, Lake Pleshcheyevo, the town of Pereslavl and the Nerl River which winds through these forests towards the ancient town of Suzdal.

The woods hereabouts are dotted with marshes and swamps and are still quite wild. The Slavs of Kiev Rus regarded these lands beyond the great forests of the Oka region as the end of the world. I often come here armed with my camera to get candid shots of woodgrouse and heath-cocks. When driving on the local roads one has always to be careful of elk crossings. There were certainly deer here at one time, for there is a golden hart on the coat-of-arms of Rostov. Driving through the forest is like driving along the bottom of a deep valley. It is a hilly terrain, and the cars either coast downhill or slowly climb the many rises. Numerous motorcycles carrying passengers armed with shotguns, fishing tackle or baskets for mushrooms overtake the cars, and the forest swallows them all.

As one approaches Rostov the road becomes a constant decline, the forests thin out and disappear. Stopping to look about, you see that the landscape is similar to the black-earth steppe regions. Indeed, these wheat fields feed the North. There was a time when forests grew in this valley, but the tillers of yore destroyed them. Novgorod the Great subsisted on Rostov wheat, and famine threatened whenever the trade routes were severed in times of internecine war. From the highway I glimpsed a tractor pulling two sowers and tried to imagine a tiller and his wooden plough working these same fields which for a thousand years have nurtured generations.

A large lake glittered ahead and a white city rose above it. In years gone by one would have heard the bells tolling at such close range. We had reached Rostov.

"The devil went to Rostov, but the crosses warded him off" is an old saying that mirrors the appearance of the ancient city. Rostov today is not a monument to the past but, rather, a typical 19th century provincial Russian town. There are the old merchants' shops and warehouses, the one- and two-story houses with stucco molding and columns. This is how Rostov has come down to us. In more recent centuries it was known for its fairs and its vegetable growers, who supplied the markets of St.Petersburg and Moscow. This was not merely a matter of great quantities of fresh vegetables, since the growers carried off many a gold medal and prize for their winning entries at the Paris agricultural fairs. Many of the old secrets of their trade have been forgotten, but to this day Rostov onions are unexcelled, while nowheres else in Central Russia are pickles as good, or are summer tomatoes kept fresh far into the winter.

One can search for traces of prehistoric settlements near the lake, and children digging near the banks still come up with shards, flint arrowheads and carved bone fishhooks, which means that the huts of Stone Age man stood on piles where the rows of motorboats are now moored along the pier. Living on the lakefront must have always been convenient if a town eventually rose here.

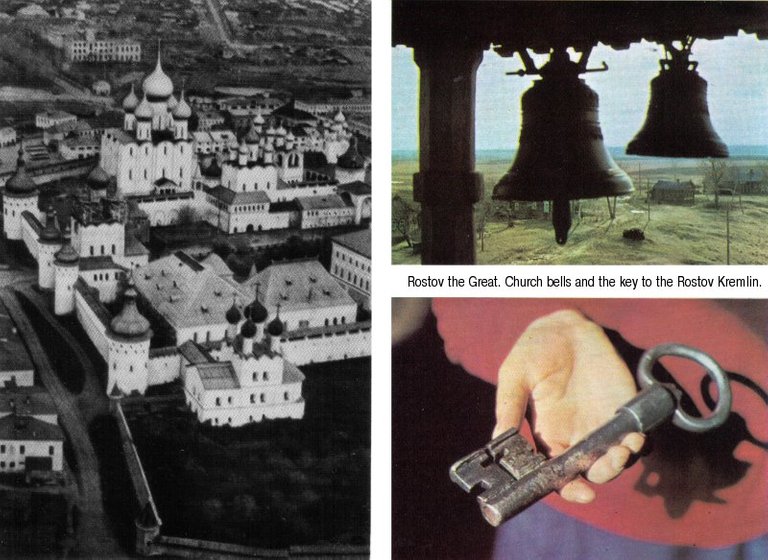

Standing on the shore of Lake Nero in the evening, when the quiet flow of daily life has subsided, one can hear the bell on the fire tower tolling. Bong! Bong! The voice of Time carries over the water. Eleven centuries. Not every year, and not even every century has left its mark. However, one century, in particular, has come down to us. Historians, architects, painters and sightseers all flock here to see the wonderful creation that has earned Rostov the fame it enjoys today. The rest of the town merely serves as a backdrop for the precious white stone structure built by Russian masons and known as the Rostov Kremlin.

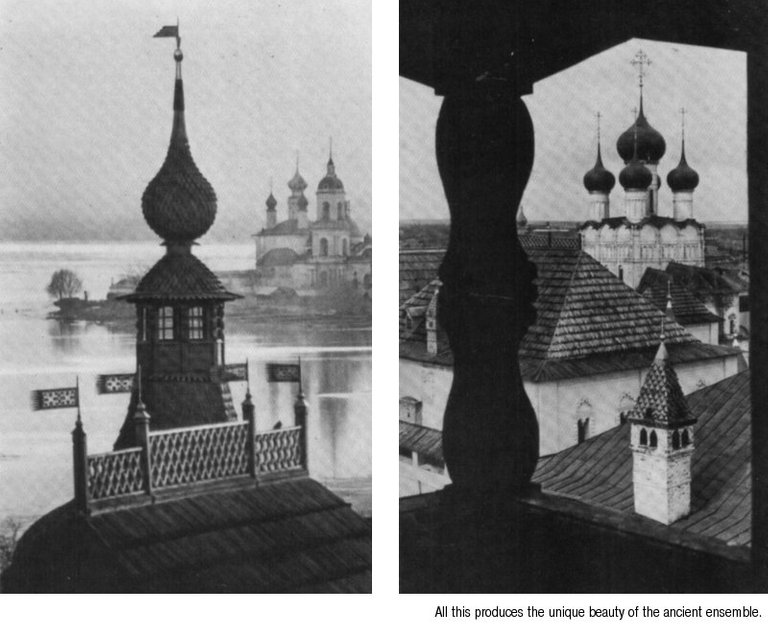

Since the buildings are on the lake-front, the best view is to be had from a boat. Using a punting pole, you push off from the silt. The sight that soon greets your eyes is never to be forgotten. All that you have heard about ancient cities in the fairy-tales of your childhood suddenly appears before you. Then you realize that the "Tale of the City of Kitezh" and the "Tale of the Island of Buyan" were written after some ancient story-teller had seen these white stone buildings from the lake. Ever since, similar ancient cities have appeared in Russian epic poems, operas, paintings and children's stories.

I saw the Rostov Kremlin gleaming white against the sky of twilight, mirrored in every detail in the still waters. There were the towers, the wall and loopholes, the porticoes, the small windows, the gates, the carved roofs, the countless heaven-reaching cupolas, with each part interdependent and bound skillfully to the rest to form a great and beautiful whole known as an architectural ensemble. One finds the same cluster of beauty in the Moscow Kremlin. There are not many such ensembles on this earth.

The enchantment does not diminish, but is actually heightened as one examines at close range and in detail the mighty, three-meter thick brick walls, the little golden flags atop the pointed green smoke-pipes, the carved stone over the windows and gates, the ironclad doors and the blue and ochre frescoes inside the churches.

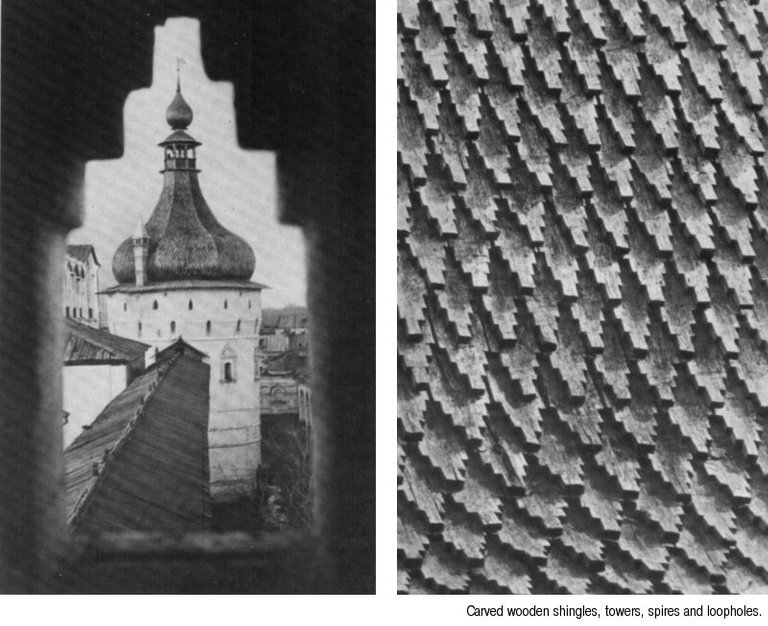

The Rostov Kremlin is a fortress wall with watchtowers that guard the inner yard, where churches, chapels and ancient structures fill most of the available space. The first thing that catches your eye and calls for closer scrutiny and for the inevitable questions is the unusual roofing of the towers. Carved wooden shingles are an ancient Russian invention. The base of the Kremlin spires in

Moscow is done in the same style, though these are not of wood. The Rostov towers are covered with carved aspen shingles. Weather-beaten asp resembles nothing as much as fine old silver. This secret was known to the ancient craftsmen, but the process of curing the wood was thought to have been forgotten. Recently* however, an old carpenter was located in Karelia who remembered the secret of making wood look like silver.

We must be thankful to the restorers, for they patiently hewed and carved each shingle, laying row upon row to produce the effect of a coat of mail. Thus, the ancient structures have regained their original unique appearance.

Neither one nor even two visits are sufficient to fully appreciate the beauty of the Rostov Kremlin. As is the case with a true masterpiece, there is always something new to be discovered. You may suddenly see a building from a new angle, silhouetted against a sunset or, as you wander along the narrow lanes between the walls, you may come upon an unusual combination of towers and cupolas, carved cornices and gilded spires. In passing through the covered gallery atop the fortress wall you see the Kremlin variously through a wide slit under the roof, a loophole, the metal grating or the stained glass of a small window. The top of the wall under your feet is over three meters across and contains many small chambers, corridors and skylights. Every now and then a new secret chamber is discovered within the wall.

It is difficult to single out any one object or structure here. Still, the free-standing Church of St. John the Divine is outstanding. Its classically simple lines remind me of a youth gazing over the fortress wall at the blue vastness beyond the lake. The Church of the Assumption outside the wall which was the meeting place of the popular assembly in ancient Rostov, carries the stamp of regal power. Although this huge church was built for the glory of God, it reflects the unbending spirit and artistry of the mortals who created it.

The Rostov Kremlin is the 17th century's message for us. The structures provide an insight into the technological achievements, the tastes and ideals of the men who built it. We can visualize the anthill of activity here, the masons and carpenters in their homespun shirts and trousers and their long hair held in place by a leather thong, when construction, breathtaking in scope for the times, was under way. The names of the builders and painters have not come down to us, though the family of one Pyotr Dosayev, a stonemason, is noted in the church calendar following that of Metropolitan Iona Sysoyevich and heading the list of notable men. A stonemason had to achieve something truly outstanding to have his name entered for prayers beside those of the boyars and high church officials. This gives us reason to believe that Pyotr Dosayev was one of the master builders of the Rostov Kremlin, while Metropolitan Iona Sysoyevich was chiefly responsible for its inception and construction. Iona was the son of a poor village priest who rose from the rank of monk to the top of the ecclesiastical ladder, becoming the head of the Russian

Church with his see in Moscow. However, he fell into disfavor and returned to Rostov. From then on this man of the people devoted himself entirely to the task of erecting the Kremlin.

Work continued unabated under Iona's direction for two decades. Blacksmiths, stonemasons, carpenters, icon-painters and goldsmiths toiled on tirelessly. One can assume that Iona did not limit his stay to Rostov and that he travelled to other cities and learned what he could of their architecture, of the best that Russia's craftsmen had created. This was a time when foreign styles were beginning to appear in Russia, and many late 17th century structures were distorted by these alien influences, Iona had no desire to follow the current fashion in architecture and did not vacillate when choosing his models. That is why one can now view these architectural masterpieces, so truly Russian in appearance, in Rostov. The white stone structures have come to us as a song in which our ancestors' understanding of beauty is expressed so majestically.

I brought back several souvenirs from Rostov: a flint arrowhead, an aspen shingle which so resembles the battledore village women once used to pound their washing, and a small enamelled icon the size of a wristwatch, done in the 19th century. (The craft of enamel-painting still exists in Rostov). I especially treasure my LP record of Rostov's church bells. Given today's preponderance of "canned music", one often feels a need to hear the deep and resonant sounds produced by these ancient musical instruments. A chasm seems to lie between the apparently primitive sounds produced on the belltowers and the refined virtuosity of symphonic music. But, honestly, I felt truly moved as I listened to the solemn tolling of the big bell, supported by the ringing of the small bells and then, in the pauses between the clanging, hearing the chirping of sparrows recorded by the microphone set up on the belltower. The walls of my room seemed to dissolve, giving way to vast open spaces. Then, when the alarm bell drowned out all the others, my imagination conjured up a crowd of people hurrying to the assembly square, the confusion of a fire, or an enemy force approaching the walls of the city.

Since ancient times the life of the people of Rus was accompanied by the ringing of bells. This ringing joined the people on festive occasions and when an enemy threatened, it summoned them to assembly and pointed out the way to travellers during storms, while the hour bell tolled the hours of the day and night. The mobilizing force of the bells must have been very great if Hertzen named his rebel journal Kolokol (The Bell), if the first thing a conqueror did was carry off the assembly bell, while the Russian tsars exiled bells, as they did people, for insurgency.

Peter the Great had many of Russia's bells melted into cannons. I recall the time in the 1930s when the church bells in our village of Orlovo were taken down. A huge crowd gathered. The women crossed themselves and said that the bells would be made into tractors. Indeed, that same year a new tractor, its spurs glittering in the sun, drove down the length of the village street, making real to us boys the strange transformation from bell to machine.

Today's loudspeaker is certainly more convenient than a bell. Yet, it is interesting to listen to and understand the sounds of the past. Remember the solemn tolling of the bells in the film version of War and Peace? Another film, Seven Notes in the Silence, has a wonderful sequence about a belltower and bell-ringers. Finally, there is this LP recording, which brings the bells right into your home.

The belltower of the Church of the Assumption was also built during Iona Sysoyevich's time and is another architectural masterpiece. It serves to join the cathedral to the rest of the Kremlin.

However, it carried out its main function, that of being a belltower, most excellently through the centuries. The main bell, known as the Sysoi, weighs 32 tons. The five other bells weigh less and, therefore, are not as loud as the Sysoi, but each has its own name, none of which is of a religious nature (the Goat, the Swan, the Ram, etc.), while the seven small bells are nameless.

It was no easy task to cast, raise to a height of a six-story building and secure these hundreds of tons of bronze, since there were neither truck tractors nor tower cranes in the 17th century. That is why very big bells were usually cast near the belltower in which they were to be installed. There is a lovely pond in the very center of the Rostov Kremlin. This was originally the foundry pit for the big bell. A great crowd gathered here at the day the bell was to be cast. The cascade of sparks from the molten bronze descended into the pit together with the blacksmiths' smoking aprons and a shower of silver coins "to give the bell a pure tone". The occasion can be compared to a spaceship launching today, and the moment when a new bell issued its first sound was probably as portentous as the successful orbiting of a spacecraft. "In my little yard here, I cast bells, that sound clear, folks come from far and hear," Iona Sysoyevich wrote to a contemporary of his. One senses the jest, but also a consciousness of the enormity of the task. It takes a wise man to make fun of himself, Iona Sysoyevich, the founding father of the Rostov Kremlin, was just such a man. The largest and last of the bells was cast shortly before his death. While apparently pondering over life's vagaries, he acknowledged his humble peasant origin by naming the bell Sysoi, after his father.

While musing here by the belltower, I would like to mention that the bells do not ring by themselves. The eternal bronze is as silent as the grave. Do not think that it is as easy to ring a church bell as it is to ring a dinner bell. Naturally, given some practice one can even swing the ton and a half tongue of the Sysoi. But it takes a master, a musician with a good ear and an understanding of the task, to produce a melody on ten bells. The size of the musical instrument calls for at least five bell-ringers, which brings us face to face with a rather unique orchestra.

In its centuries-long history Rostov has begotten many generations of master bell-ringers. They were the creators of special music for the bells; they composed and arranged music, so that what we hear today are indeed fine examples of the art. Hector Berlioz, Fyodor Chaliapin and Maxim Gorky all visited Rostov to hear its bells.

Four old men are the last in the long line of Rostov's bell-ringers. When they die the only chance we will have of hearing the voice of the past will be lost. One cannot remain indifferent to this fact. Their skill must be passed on. This was no problem in olden times, when the bells tolled on many occasions. Now, however, they only sound on special occasions (for recordings, or as background music for a film). Besides, the old men have a hard time climbing the steps of the belltower. That means someone must be taught. Perhaps a special sum must be put aside to pay the men for teaching their future pupils. We spend so much on restoring architectural monuments. This, too, must be regarded as the restoration of a monument (a unique one!), and this task cannot be put off.

There is always the danger of some priceless work of art being lost. Thus, when the portrait of Mona Lisa was brought to New York it was put on display behind bullet-proof glass and guarded by policemen to make sure it would not be stolen. Masterpieces like the Rostov Kremlin cannot be carried off, but they can be lost through negligence, ignorance and indifference. The Rostov Kremlin has suffered from all three. The trouble began immediately after Iona Sysoyevich's death. First, the buildings still under construction were not given the attention they had received previously. In time, work dwindled and they were completely forgotten. The unattended manuscripts and scrolls moldered away, as did the icons and archives. Local government officials moved their offices into the chambers, while the town's merchants turned the various buildings into storehouses for wine and salt. A slaughterhouse was set up by the wall where the recluse Grigory "a man of great learning", once lived. Things came to such a pass that General Betancourt of the Army Engineers proposed that the Kremlin be pulled down and a European-style inn for travelling merchants be built on the site. This occurred nineteen years before d'Anthes shot the great Russian poet Pushkin and can serve as a good example of the fact that if we do not care to preserve our country's heritage, others will feel no compunction about destroying it. Luckily, the crime of destroying the Kremlin was averted, although the top of the bell-tower and the top floor of the Krasnaya Chamber were pulled down. Thanks to the efforts of such patriots as Titov and Shlyakov of Rostov, both of whom should be remembered, reconstruction of the Kremlin was begun late in the last century. The great monument lives on.

A hurricane, unusual in these parts, swept over Rostov in 1953, its narrow path passing directly over the Kremlin. Eyewitnesses report that the roofing and covering of the cupolas was blown across the lake like paper. Once again disaster threatened. This time, however, there could be no question of whether to restore the Kremlin or not. The State allotted a considerable sum for the work. Thanks to the special efforts of Vladimir Banighe, a talented architect, the Kremlin was not merely restored, it was restored in its original munificence. Painstaking research did away with all the later jarring additions and corrected the mistakes made during various hasty repairs. Although there is still a lot Jo be done, the Kremlin now appears as it was three hundred years ago.

It is pleasant to stroll through the Rostov Kremlin with someone who shares your thoughts, for then the joy you experience at every new discovery will be shared.

Still, it is sometimes necessary to be quite alone with the starry sky, the sea, the forest and meadows, as with art that belongs to eternity.

I saw the Rostov Kremlin several times in the evening when I strolled along its winding paths. There will always be the put-put of a motorboat or two out on the lake; you can hear people talking outside the wall and the clock striking on the town tower. Perhaps an unseen airplane will buzz by in the fading light. The silent, faintly white Kremlin looms over the muted sounds of the evening.

A feeling of the past that is connected with all that surrounds man and is important to him in the present has always given him confidence in the future and a sense of balance in his reflections on the meaning of life and his place on earth. We say the monuments of the past and of the Revolution instill in us a sense of belonging to our country and a responsibility for its future. This is both true and important. But this is not all. A discovery of the beauty that was bequeathed to us by generations past makes one feel doubly responsible. This is a great and wonderful feeling. If the Rostov Kremlin will further develop a sense of being needed we can only be thankful to it for its existence.

beautiful material have posted congratulations

Fascinating. Is Rostov part of the golden circle, the famous cities surrounding Moscow?