A hammered copper pitcher stands on my shelf beside the samovar and the ceramic Georgian pitchers. An old coppersmith in Khiva made this traditional eastern vessel as I watched him in his small stall at the bazaar. There was a fire burning on the earthen floor. The old man kept adding charcoal from a little pail, working the patched leather bellows and hammering away skillfully at the copper sheet with a little hammer. The youth sitting next to him was also a coppersmith. The air was filled with the staccatto of their hammers, acrid fumes and the smell of fried fish coming from a teahouse nearby. I spent two days wandering about Khiva with the strange feeling that it was all a dream. For some reason or other I used to think that there was no such city any more, though it had once existed in the distant past, when it was known as the khanate of Khiva. But it does exist! It lives on quietly and unobtrusively, never mentioned in the weather forecasts or the news reports.

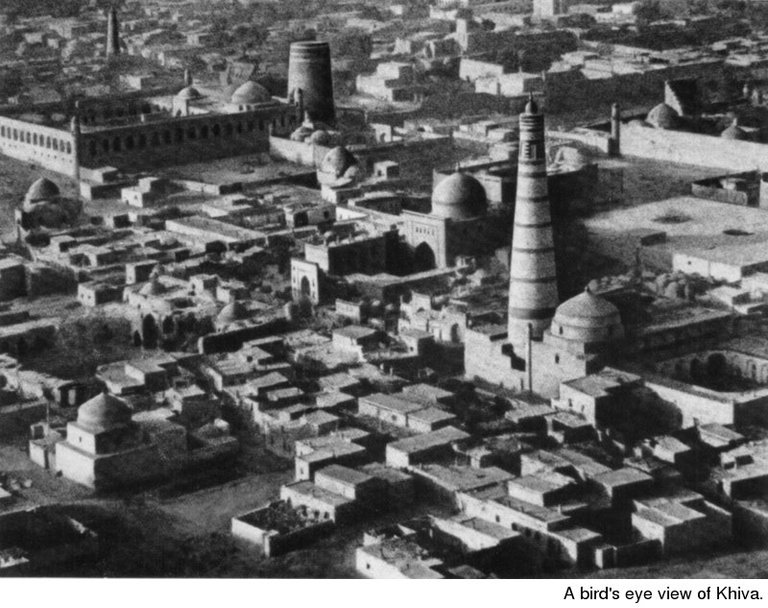

I first saw the city from the air. During one of my shots the small plane nearly grazed the top of the highest minaret. We had an excellent view of the settled clay of the high wall, its towers, loopholes and four gates facing north, south, east and west. The wall was like a gray belt girdling the anthill of old buildings.

It seemed that if the belt were to tear the city would immediately splash out onto the dusty plain. This would probably have happened if Khiva had continued to grow. Moscow and many other old cities have expanded in this way, growing beyond the original walls of their fortresses. A new city of Khiva is going up beside the old one, but the ancient wall has not been broken. It firmly encompasses the charm of the medieval city, making it a precious gift from the past.

I was so fascinated as I looked down at the labyrinth of flat roofs, the cupolas that resembled shaven heads, the towers, minarets, palaces and houses that I kept forgetting to snap the shutter. "That was the slave market! The khan's baths! The unfinished minaret!" the pilot kept shouting into my ear. The walls and cupolas were a sparkling blue, though the predominant color here is dusty-gray. Later, as I wandered through the crooked lanes and squares I saw that nearly all the buildings were of clay. The walls of the houses, the round clay ovens and even the palaces were made of adobe brick. A person born and raised here would probably think the whole world was made of clay. The city would have certainly melted away if this were a place where it rained often. But Khiva has stood here in arid Asia for a thousand years, and it seems it will stand another thousand.

I cannot list the monuments of Khiva, since the city itself is a monument (fortunately, this is now the attitude towards it). Some of the buildings are more recent, though some have virtually sunk into the ground. There are palaces faced with glazed tile and there are shabby huts whose doors, nevertheless, are nearly always adorned with carving. Of the many landmarks I especially recall the tomb of Pakhlavan-Mahmud, a furrier, strongman, wrestler and poet who died six hundred and fifty years ago. The people venerated this tomb to such an extent that the rulers willed that they all be buried beside the poet. I recall drinking tea one evening in the house of Usup-aka Tashpulatov. A clean red blanket was spread on the floor. On it was a plate stacked high with flatcakes. The samovar bubbled, and a cricket chirped as we conducted our unhurried conversation. I recall climbing the circular staircase inside a minaret and the call of the muezzin. I recall a young voice singing Suliko, a Georgian folk song, one dark evening.

I especially remember the nights in Khiva. Any city changes beyond recognition at night. Here, however, one loses track of time completely. You forget how you came to be here, and where you are. The crooked lanes lead you off to the right and then to the left. The buildings are black. Their shapes seem strange. If someone coughs across town you can hear him. If someone is walking along in the dark, his footsteps echo in the palace niches. A sewing machine clatters. Someone calls to a dog.

A carved gate in Khiva. This beautiful,

ancient city abounds in wood carvings,

hammered metal ornaments and carved stone.

The ringing of the coppersmiths' anvils,

the voice of a muezzin, the smell of charcoal

fires, ripening melons, fried fish and sun-baked

clay fill the air.

I wandered about the labyrinth of narrow, winding streets, then suddenly recognized the silhouette of a Byelorus tractor. How had it managed to squeeze through here? And what was this cliff? Why, it was the city wall! I scrambled up the clay slope that was still warm from the sun. Seen from above, the medieval city appeared blue in the moonlight. The turquoise scale-like tiles of the minarets sparkled and fragrant smoke from a bonfire drifted over the rooftops. A girl and her mother were baking flatcakes in a yard beside the wall. They had heated the round clay oven by building a fire inside it and were now tossing rounds of dough in through the opening.

The smell of baking bread wafted towards me.

Khiva today is two very distinct cities: the Old Town and the new. The new city is of little interest to visitors, but it has all the modern conveniences and is green, cool and clean. There is a garment factory, a rug factory and one that makes household utensils. However, the profits from all three would seem like nothing if the historic sights of ancient Khiva were advertised and put to commercial use. When the advantages of tourism are discussed, something Count Rothschild allegedly said when visiting Suzdal is often quoted: "Give me this town for three years and I'll double my fortune." At present Khiva's "bank account" is more than modest,'and no wonder, since the only hotel accommodates twenty-five persons and the one in the neighboring town of Urgench accommodates about a hundred. There is even a certain fear of large numbers of visitors. Nevertheless, one should certainly visit Khiva, finding lodgings for a day or two with some local family or even pitching a tent outside the city wall. I am sure no one will berate me for having enticed him into coming to this amazing city.

Really nice description of Khiva. Where is it located? Russia? (Sorry if I missed that part.)