I've known the old song about Lake Baikal since I was a child. Our neighbor, Grandpa Yegor, the lame carpenter, sang it in the evenings as he sat on his porch. When he got to the words "the sacred Baikal" his voice would begin to ring, and we children thought he would surely begin crossing himself. Grandpa Yegor knew many songs, but if someone ever asked him to sing, he would always, sing the one about Lake Baikal.

In later years, whenever I was home on vacation, I noticed that Grandpa Yegor hardly ever sang any more. Still, if anyone started the famous song, he would always join in, though he would then sigh and say, "I'm not much of a singer any more."

Then Grandpa Yegor died. Six withered old women followed his coffin, singing psalms in cracked voices. He lay very straight and, I thought, with an angry look on his face. "You'd think he was sleeping," the old women whispered. I felt he would suddenly open his eyes and shout: "Shut up! Can't you sing the song about Lake Baikal!"

I don't know why, perhaps it all started with the song, but my eyes have always been drawn to the icy-blue spot on the map with the faraway word "Baikal" on it. Everything I could have learned from books and people had been read and discussed. I wanted to know as much as I could about this deepest, coldest and purest lake, a lake made famous by a song. "Over three hundred tributaries feed the lake and one river has its source in it...", "One can see the stones on the bottom...", "The omul is an unexcelled fish".

I was on my way to Siberia. Vendors at the stations hundreds of kilometers from Lake Baikal were selling fried omul. The closer we got to the lake, the fewer passengers would remain on the train during the stops. Everyone brought back greasy packets and solemnly informed the others that they contained fried omul.

I tasted some. To me it was a fish like any other. Unfortunately, it was quickly growing dark when we finally reached the lake. The passengers peered out the windows and gathered on the platforms, but it was impossible to see anything. Yet, we were right beside the lake. The conductor said: "If anybody jumps, he'll land right in the lake." But by then it was too dark to make out the water.

I had travelled through and flown over many parts of Siberia about a dozen times, but I had never yet seen Lake Baikal.

Here it was now.

"Lake Baikal!" the driver said, opening the door and looking at me as though he had brought a guest to his home and was showing him around, knowing for sure that I would like everything I saw.

Though it was the end of June, a March chill rose from the shore beyond the thickets. We had so recently been overcome by the heat in the taiga, but here it was cold enough for winter jackets. We could not see the lake as we made our way through the clumps of wild cherry. The icy breath of the water had held up their blossoming, and the trees had just put out their tiny leaves. The belated blossoms of marsh tea were a deep lavender, while the small birch at the water's edge would not believe it was summer and stood stark naked still.

The taiga rolls down the mountains to the vast expanses of the lake in terraces of green, halting at the water's edge. After dipping their roots into the water the larches, birches and pines decided not to go in for a swim after all and stopped, while the taiga, pressing on from behind, could not. That is why there is such a crush along the shore. Giant trees lay on the ground, forming a green barricade at the approaches to the lake.

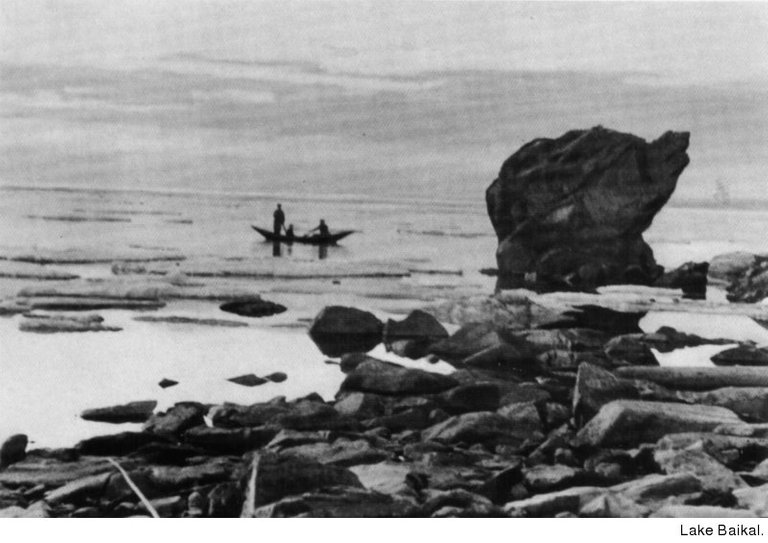

It is strange to see April and June side-by-side here. As you face the lake, which so resembles the Volga during the spring high water, all the smells of summer are at your back. Here is the same expanse of water, the same clusters of ice floes, the same lone boat silhouetted against the sky.

The ice here breaks up late in the year, with ice floes dotting the surface till the end of May. They finally converge on the shores in June to slowly melt by the boulders.

We stood on the pebbly shore, hats in hand, beside boulders half the size of a house. The high-tide mark was strongly etched, for the crystal-clear water would not stand for trash. On stormy days the lake tosses the wreckage of boats and rafts, logs, snags and dead fish onto the shore. There is never a speck of dirt in the water!

The cold, majestic blue reaches off to the horizon where blue mountains swathed in the purple haze of twilight fade into the sunset.

It is a Saturday evening. Fishermen have come in from the distant settlements along the forest rivers. They glide skillfully through the maze of floes, fishing for grayling. Some have nets, others just rods.

Their bait is bullhead roe which they find under the boulders on the shore.

We walked over to a campfire to join a group of fishermen. They fried us some omul on wooden skewers. Fish prepared in this primitive manner is delicious. Having had our fill, we piled *more driftwood onto the fire. Warm waves of summer, fragrant with the smell of blossoming wild cherry, rolled down the mountain slopes. A cuckoo called. Every now and then another floe would crumble with a loud swishing sound.

"Is there any wildlife on the lake?"

One of the men raised his gun and fired into the air. The shot was instantly followed by the sound of flapping wings. Ducks and swans had risen into the air.

We had planned on taking the Barguzin Road to the lake's hot springs. However, it was too late to start out and so we decided to spend the night with the fishermen. We sat around talking about Lake Baikal before calling it a day. Each man had a story to tell.

"Three years ago we took a skipper off a mast. His crew was lost in a storm, and he'd been in the water for forty-eight hours. He was unconscious, but he was hanging on to that mast for dear life."

"Remember the time the rafts were smashed?"

The driver put an armful of springy marsh tea under his head for a pillow and said, "I used to drive a geologist around here. He was looking for some kind of rocks. That winter he asked me to send some of these branches to his family by parcel post. He said if you put them in water they'd blossom in a week. That's funny. Believe it or not, I sent three packages of naked branches to Moscow for him that winter."

The ice rustled. A bird winged through the night sky. Soon we were all asleep.

That night I dreamed of blossoming marsh tea, ice floes, flocks of starlled swans and Grandpa Yegor, the viltage carpenter. He was standing on the bridge of a small steamer, talking to a geologist and saying, "I'm glad you found those rocks. Now let's sing the song about Lake Baikal."