Electricity and Electronics

The most obvious reason for learning about modern electronics is that electronic devices are ubiquitous in our world. Consider some of the things you use that are electronic: an iPad, a smartphone, a laptop, a TV, the instrument panel of your car, a GPS system, a camera, the loudspeaker in your audio system, and so on. We’ll start in this lecture by distinguishing electricity—the more mundane topic—from electronics— the more sophisticated. Then, we’ll cover a bit of background on basic electricity. Key topics in this lecture include the following:

-Electricity and electronics

-A brief history of electronics

-Moore’s law

-Volts, amps, and watts

-Resistance and Ohm’s law.

Electricity and Electronics

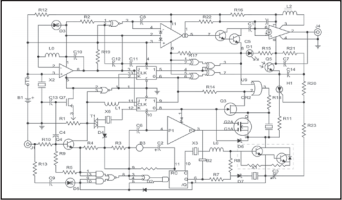

Electronics involves the control of one electrical circuit by another, and it involves using devices that allow that kind of control, often with weaker electrical quantities controlling stronger ones. An electrical circuit is an interconnection of components intended to do something useful, such as display video or amplify sound. Usually—but not always—a circuit includes a source of energy.

A Brief History of Electronics

For the first half of the 20th century, the device used to control electric current was the vacuum tube.

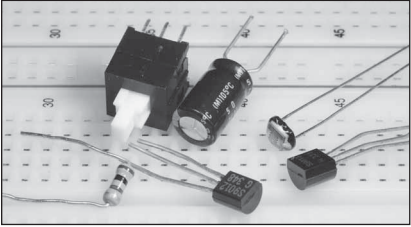

These were evacuated glass tubes containing metal electrodes, between which electrons flowed the tubes were designed in different ways for different functions. By applying different electrical signals to the grid (the control electrode in the tube), the amount of current that flowed through the tube could be controlled. In the 1950s, a revolution occurred in electronics with the invention of the transistor.

The transistor did exactly what the vacuum tube did—that is, it allowed one circuit to control another—but it was much smaller, and it was a solid-state device.

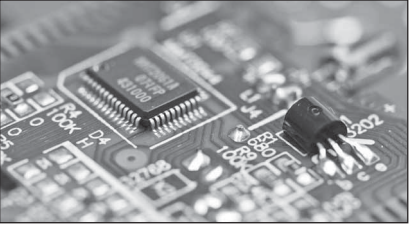

In the late 1960s and early 1970s came yet another development: the technological ability to interconnect many transistors and other electronic components on a single tiny wafer of the element silicon. That was the integrated circuit. Today, integrated circuits contain anywhere from a handful to billions of individual transistors.

Moore’s Law

In 1965, Gordon Moore, a cofounder of Intel Corporation, made the following prediction: As we learn to make integrated circuits increasingly compact, the number of transistors on a single chip will double every 18 months. Actually, the number of transistors has doubled about every 2 years. Moore’s prediction is known as Moore’s law, and it will probably hold for at least another 10 years.

Volts, Amps, and Watts

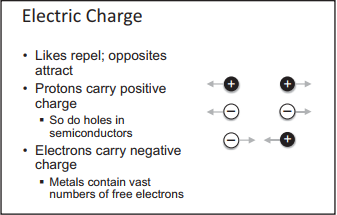

Electric charge is a fundamental property of matter. It comes in two varieties: positive and negative. The protons that are in atomic nuclei are the main carriers of positive charge, and electrons are carriers of negative charge. There are vast numbers of free electrons in metals.

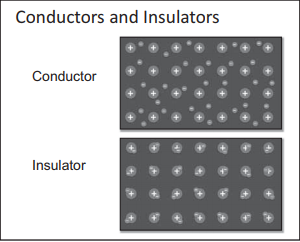

We can talk about free charges as a way of distinguishing two kinds of materials: conductors and insulators. An electrical conductor is a material containing charges that are free to move. In metals, the most common conductors, those free charges, are electrons. Typically, one or two electrons at the outermost periphery of the metal atoms become free, not bound to individual atoms. They’re free to move throughout the metal, and that’s what makes the material a conductor. An insulator is a material lacking free charges. In an insulator, all the individual electrons are bound tightly to the atoms and can’t be moved.

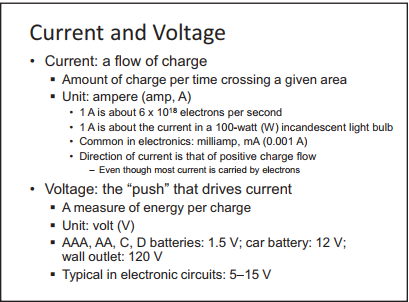

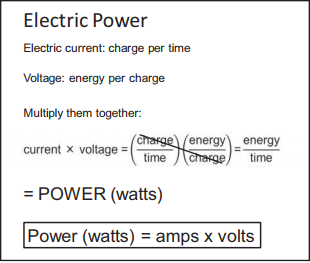

Electric current is a flow of charge, which is measured in amperes (A). Voltage is the push that drives current through a wire or an electrical or electronic device. It's a measure of the energy per charge, and its unit is volt (V)

Multiplying current (flow of charge) by voltage (push) gives us a third important quantity, energy per time, or electric power. Power is the rate at which a system delivers, consumes, loses, produces, or transfers energy from one form to another. Power is measured in watts (W).

Resistance and Ohm’s Law

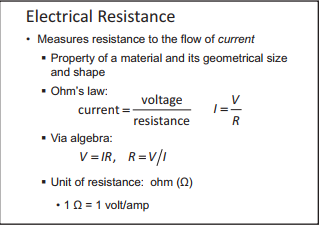

Typically, conductors have resistance; they don't let current flow easily. The resistance of a particular component is a function of both the material it’s made of and its geometrical size and shape. There’s a simple relationship, known as Ohm’s law, between current and voltage: current = voltage/resistance, or I = V/R. The unit of the resistance is the ohm. Ohm's law can be written in three different forms, but they’re all equivalent: I = V/R, V = IR, or R = V/I.

Source: https://guidebookstgc.snagfilms.com/1162_ModernElectronicsNOBADGE.pdf

Not indicating that the content you copy/paste is not your original work could be seen as plagiarism.

Some tips to share content and add value:

Repeated plagiarized posts are considered spam. Spam is discouraged by the community, and may result in action from the cheetah bot.

Creative Commons: If you are posting content under a Creative Commons license, please attribute and link according to the specific license. If you are posting content under CC0 or Public Domain please consider noting that at the end of your post.

If you are actually the original author, please do reply to let us know!

Thank You!

This post received a 3% upvote from @randowhale thanks to @cryptoracle! For more information, click here!

The jump to integrated circuits increased the number of calculations and speed in computers. With further miniaturization, speed power, and memory of computers have proportionally increased. Because electricity travels about a billionth of a second; the smaller the distance the greater the speed of the computers.

You've really simplified electronics. Kudos!

Thanks a lot :)