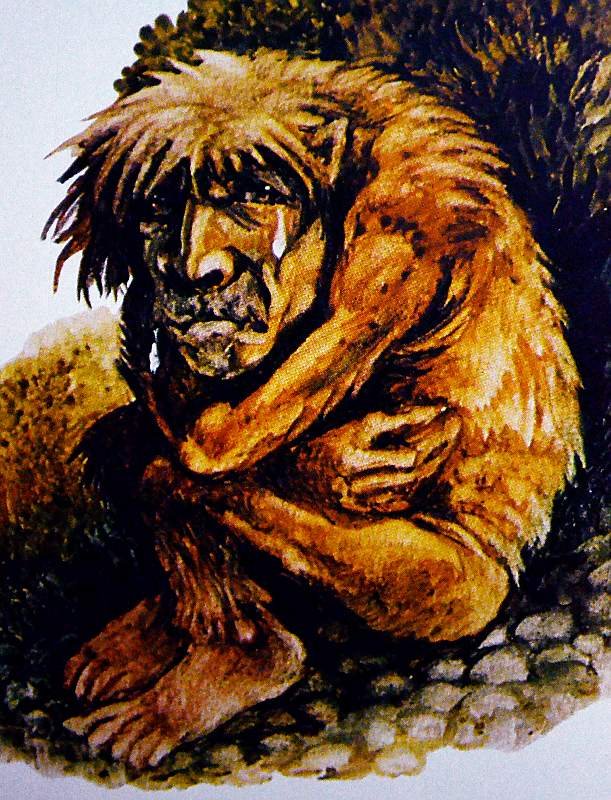

The familiar of witches and sorcerers most feared by

the Bantu is the tokoloshe (the dwarf). In her book

Suspicion is my name, Barbara Tyrrell, a renowned

authority on Bantu folklore, describes the tokoloshe

as follows:

‘_ _ _ it is the same height as the manzindane (fairy

man) but it has a wider body. It also has smooth

ochre-coloured body-fur, has hair hanging over

the forehead, a small moustache, hair on the feet

and backs of the hands but none on the palms. The

hands and feet are small like those of a monkey. It

has hairy ears pressed back against the skull and a

penis that looks more like a tail and is indeed

referred to as a “tail”.

The hair on the head is longer than that of the

body and its eyes are black, small and narrow. It

wears no clothes and lives in holes among stones

and in the river. This is a wild creature and ...is

not itself bad. It is used by evil wizards who catch

it in the river, kill it and make it into medicine,

creating a live yet not a live thing. This creation of

their own magic is then their servant for evil.’

The malevolence behind this macabre being does not

spring from the tokoloshe himself but from his evil

master, the sorcerer, whose main aim and pleasure in

life is to cause misery and strife among his fellow men.

It is the sorcerer who sends the tokoloshe on his wicked

errands. The tokoloshe’s main asset is his ability to

render himself invisible. Unseen, he can creep into a

hut to place poison in strategic places, or hide a buck’s

horn filled with vile concoctions in the thatch or in the

river mud near the spot where the drinking pots are

filled. While a victim is eating the tokoloshe can even

drop a little bad medicine into the spoon of food he or

she is about to swallow.

Catching Tokoloshe

The tokoloshe’s undoing often comes through his crav-

ing for fresh milk, which he drinks straight from the

cow’s udder. To cover this theft, he lets the calves into

the kraal with their mothers, so that the farmer is fooled

into thinking that it is they that have drunk all the milk.

After a while, it usually occurs to the man that he is

being robbed by a tokoloshe and he employs the ser-

vices of a witchdoctor or herbalist. As the tokoloshe

always enters the kraal from the rear end of the enclos-

ure, the herbalist sets his traps there. He draws a magic

circle and sprinkles his enchanted medicine where he

knows the dwarf will walk. If the tokoloshe falls into the

trap, he will stand there paralysed, with his powers of

invisibility destroyed. He cannot move a finger, but if a

person shouts, or exclaims, ‘Lookl A tokoloshel’ he will

vanish immediately, as the spell will be broken. There-

fore the herbalist must make sure that he personally

captures the dwarf. This results in a sticky end for the

tokoloshe, for he is ground up, fat and bone, and turned

into strong medicine to be used by the herbalist to catch

others of his kind - a service for which the herbalist is

well rewarded!

Tokoloshe and the Girls

On a fine spring morning, five merry girls from a

nearby village came to swim in the river. They splashed

and shrieked so loudly that a tokoloshe which lived

under the river bank was awakened from his slumbers

by their rowdy behaviour. ‘All right thenl’ he thought.

‘I’ll show them that I can play that game tool’ Sounder

the water he swam, and tickled and pinched the girls.

Soon screams of fright mingled with the laughter. The

villagers became alarmed by the noise the girls were

making and came down to the river to see what was

happening.

There were the girls, yelling in both mirth and fear.

The wisest elder recognised the signs of the tokoloshe.

‘Come out of the water at once,’ he shouted.

‘We cannot,’ spluttered the girls, ‘we are stuck fast to

the bottom of the stream, and something is tickling and

pinching us! Ooh oohl’ The old man shouted for the

young men.

‘You must jump into the water to free the girls,’ he

ordered. These instructions were obeyed with alacrity

and in no time at all the girls were carried safely ashore.

This situation has no doubt been exploited many times

without the intervention of a tokoloshe - but neither the

girls nor the youths ever declared any ill effects from

their adventure.

Tokoloshe and the Children

Some people maintain that the tokoloshe is much

maligned and that he is really a mild little creature who

lives peacefully on lonely river banks, and is particu-

larly fond of children. When he can, he will lure these

boon companions away from their frog-catching and

swimming, and will lead them into the ferny coolness of

the bank where he will spread a delicious feast and

delight in seeing them fill their round tummies to burst-

ing point. Of course, when they return home in the

eveningthey refuse to eat supper, as they long for the

delicacies of the tokoloshe’s forbidden banquets. They

are sworn to secrecy, however, and will never tell where

they are meeting their friend. Only by following the

children can the worried parents hope to find the secret

meeting place. The minute the tokoloshe suspects that

he is being watched by an adult, he will pop a magic

pebble into his mouth and vanish at once. g

There is a story that once a child repaid the

toko1oshe’s generosity by stealing this pebble while the

dwarf was swimming in the stream. Cf course the child

at once became invisible and the tokoloshe spent a

frantic morning chasing after the crack of a breaking

twig, swishing grass, and the giggles of the unseen

child. At last the creature could bear it no longer; he

burst into sobs of misery, letting the tears trickle down

his furry cheeks. Even the offender wastouched by this

sad sight, and returned the tokoloshe’s pebble to him.

However the tokoloshe never regained his complete

trust in children, and this is why he is seen so rarely.

The Herd Boy and the Tokoloshes

A man had many sheep and goats, but owing to his great

fondness for beer, and attending parties where it flowed

freely, he was not able to herd them as well as he might

and they were always straying and getting lost, or being

taken by wild animals. He asked the headman of an

umzi (kraal) to lend him a herd boy. The headman

agreed, and a suitable boy was found who went off with

the beer-drinker to his kraal. At dawn the boy rose,

drove out his new master’s numerous sheep and goats to

graze, and joined the other young herders to spend a

pleasant day in their company. In the evening he

returned home, milked the cows and shut up the stock.

He was given food in his own hut, but no sooner had he

sat down to eat than many short, hairy people entered-

men, women and children - all tokoloshes. They ate

nearly all his food, and he was too frightened to protest.

The next day he again went out to herd, and when he

came home the same thing happened: as soon as he

received food, his unwelcome visitors trooped in and

atc it all, leaving him to go hungry. This continued until

one of his companions asked him, ‘Why do you look so

bony and thin, as if you would break in two, when your

master has so many animals in milk ?' The boy replied:

‘When I sit down to eat, baboon-like animals come and

eat my food.’ . .

‘How can you see them?’ asked his friend. ‘

‘They have given me umzhi to rub on my eyelids so I

can see them.’

‘Let us go over to your umzi, no-one is there now as

everyone is at a beer party. I will take my lunch with me

to hire your visitors,’ offered his friend, and the two

went to the house of the herd boy’s master, rubbed the

medicine on their eyelids, and sat down to eat. In

trooped the tokoloshes to take their food. This time,

however, the herd boy seized his stick to thrash them,

and the tokoloshes ran out in consternation at this

violent behaviour. Une, a child, fell in its haste, and the

boy killed it with one blow of his stick. Then the two

boys, scared at what they had done, ran off and hid in

the bushes of a nearby hillock. They soon saw the

owner of the umzi coming to find out what had caused

the noise. When he saw the dead tokoloshe child, he

grabbed it and went off to bury it furtively in the

garden. ‘I am not going back to my own umzi,’ said the

herd boy, and off he went, leaving his former master to

retrieve his stock from the veld himself. '

The man was annoyed, and went and complained to

the headman. ‘The boy has left me without noticel’ The

headman called the boy.

‘My child, why did you run away?’

The boy was nervous. ‘I did not wish to live any

longer with this man. I fear the tokoloshes at his umzi

because I killed their child.’ .

The man replied angrily, ‘There are no tokoloshes at

my umzi.’

‘If you deny it, I will accuse you again,’ said the boy

heatedly.

‘Very well, accuse me.’

The boy accused him, saying, ‘This man hired me to

look after his herds, then he sent tokoloshes to eat my

food. At that umzi I was always hungry and ate

nothing.’

‘Rubbishl’ retorted the man. ‘The boy is lying.

There is nothing of the sort.’ I

‘Uh yes there is,’ cried the boy. ‘When I killed the

tokoloshe child, you ran and buried it in the garden for

fear of punishment.’

The man knew that he had been observed. ‘Oh, let us

forget all about this nonsense,’ he blustered, ‘it is clear

that the boy does not want to come and work for me. I

will forgive him and let the matter drop.’

So the boy was not punished, and the man was left to

look after his livestock himself, as no herd boy would

dare to work for him for fear of his tokoloshes ...

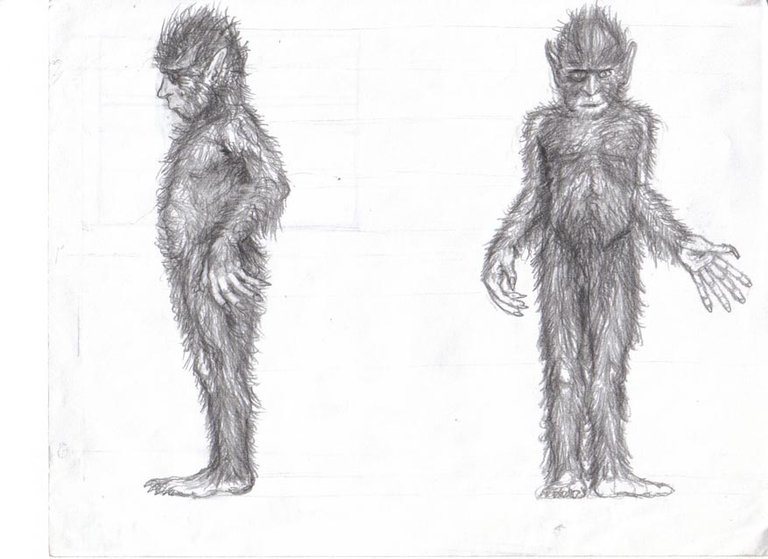

Tokoloshe.

The Pondo belief in this creature is shared by many of

the tribes of Southern Africa, especially the Xhosa

and Zulu. Tokoloshe, also known as Hili or Gilikango,

is described by the Pondo as a small hairy being with a

man’s form, but so small he only reaches to the average

person’s knee. He has hair all over his face and hair

coming out of his ears, and his face is like that of a

baboon or monkey. The penis of the male is so long that

he carries it over his shoulder, and he has only one

buttock. Both the male and female of the ‘species’

seldom wear clothing; if they do, it is made of skins.

Tokoloshe speaks with a lisp and live in crevices and

under river banks.

In addition, tokoloshe carries a charm which renders

him invisible to adults other than those who possess

him as a familiar. He can also be seen by children.

Some Pondo say that they can clearly remember

seeing tokoloshe as children, and recall having spent

pleasant days playing with him in the veld. Now, as

grown-ups,they see him no more. One among them

tells that one day, on his return from herding the flocks

as a child, he informed his parents that he had spent the

day at play with tokoloshe. The next morning being

very hot, he and his companions left their blankets off

and went to play in the cool reeds of the river bed.

When they returned later, they found tokoloshe sitting

with a blackened heap of smoking ashes before him. He

nodded portentously. ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘those are your

blankets. You see what happens to children who betray

me to grown-ups, The man also described how often

tokoloshe would come into the house at mealtimes and

filch the food from the adults’ plates, seen only by the

children.

Away from the influence of witches and sorcerers,

tokoloshe is merely mischievous, seldom evil. He wan-

ders at will, getting up to childish pranks - causing

havoc in a hut by spilling the milk, filling all the

calabashes with water, pilfering, fiddling, stealing

sweetmeats and sugar. Doubtless it is tokoloshe who

takes the blame for the deeds of many a recalcitrant

member of the family! '

Tokoloshe only becomes dangerous when he has

been caught and made the familiar of a witch, who uses

him to carry out many evil deeds. His hair is cut short

(this keeps him in a docile state) and he is housed in a

special storage hut. Nobody is specific about how

tokoloshe harms people. Some say that he has an

ikhubalo, or charm, that causes sickness, others that he

beats his victims, particularly when they have gone to

sleep. Tokoloshe, however, has a mind of his own, and

sometimes disobeys the orders of his master or mis-

tress. Several stories are told about him taking pity on

his victims and sparing them of his intended evil. This

is usually the case when he has been sent out against a

child.

A woman igqwira, or witch, always has a male

tokoloshe, who is her lover. A few maintain that men

have a female tokoloshe, but others disagree, saying

only women possess tokoloshe; indeed, those accused

of possessing him are almost always women. It is Said

a woman will always pass her tokoloshe on to her daugh-

ter. If the girl will not have him, he is insulted and kills

her. Parents instruct their children to tell them if they

see a short, hairy, little man and beat them if they admit

to playing with tokoloshe in the bush. A child who

grows up knowing tokoloshe may keep his friend into

adulthood; in this case the child becomes an umzakazhi

(sorcerer).

Tokoloshe is killed by doctors who sell his fat and

hair as a protective medicine against him. He does not

like dogs chasing him, and is terrified of mousetraps. A

blade of grass smeared with tokoloshe fat will float

upstream.

The fear and distrust in which tokoloshe is held has

led to tragedies. In 1933 a case came before the Appeal

Court at Butterworth concerning a man, Mbombela,

who had killed a child because he had mistaken it for

tokoloshe. Apparently, some children playing outside a

disused hut had seen through the chink of the door

something that had two small feet like those of a human

being. Frightened, they had called the young man,

Mbombela. He believed that what they saw was

tokoloshe§ and rushed in and killed him with a hatchet.

On dragging him out, however, hediscovered he had

killed a child. Mbombela was found guilty of murder,

but the charge was reduced to culpable homicide by the

Appeal Court on the grounds that Mbombela had

genuinely believed he was killing tokoloshe.