Sometime in the late 1800s—nobody is quite sure exactly when—a man named Vilfredo Pareto was fussing about in his garden when he made a small but interesting discovery.

Pareto noticed that a tiny number of pea pods in his garden produced the majority of the peas.

Now, Pareto was a very mathematical fellow. He worked as an economist and one of his lasting legacies was turning economics into a science rooted in hard numbers and facts. Unlike many economists of the time, Pareto's papers and books were filled with equations. And the peas in his garden had set his mathematical brain in motion.

What if this unequal distribution was present in other areas of life as well?

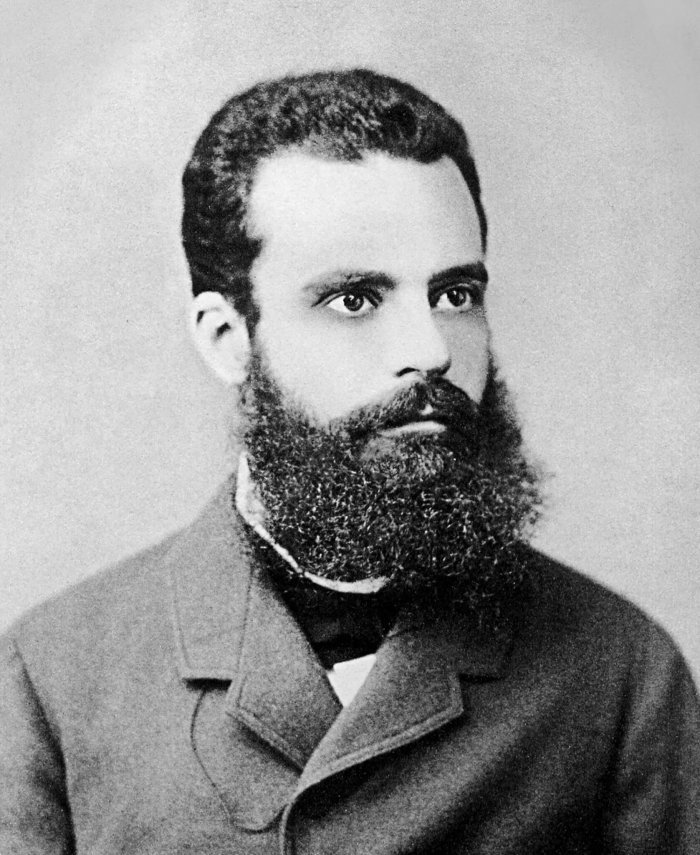

Vilfredo Pareto

The Pareto Principle

At the time, Pareto was studying wealth in various nations. As he was Italian, he began by analyzing the distribution of wealth in Italy. To his surprise, he discovered that approximately 80 percent of the land in Italy was owned by just 20 percent of the people. Similar to the pea pods in his garden, most of the resources were controlled by a minority of the players.

Pareto continued his analysis in other nations and a pattern began to emerge. For instance, after poring through the British income tax records, he noticed that approximately 30 percent of the population in Great Britain earned about 70 percent of the total income.

As he continued researching, Pareto found that the numbers were never quite the same, but the trend was remarkably consistent. The majority of rewards always seemed to accrue to a small percentage of people. This idea that a small number of things account for the majority of the results became known as the Pareto Principle or, more commonly, the 80/20 Rule.

Inequality, Everywhere

In the decades that followed, Pareto's work practically became gospel for economists. Once he opened the world's eyes to this idea, people started seeing it everywhere. And the 80/20 Rule is more prevalent now than ever before.

For example, through the 2015-2016 season in the National Basketball Association, 20 percent of franchises have won 75.3 percent of the championships. Furthermore, just two franchises—the Boston Celtics and the Los Angeles Lakers—have won nearly half of all the championships in NBA history. Like Pareto's pea pods, a few teams account for the majority of the rewards.

The numbers are even more extreme in soccer. While 77 different nations have competed in the World Cup, just three countries—Brazil, Germany, and Italy—have won 13 of the first 20 World Cup tournaments.

Examples of the Pareto Principle exist in everything from real estate to income inequality to tech startups. In the 1950s, three percent of Guatemalans owned 70 percent of the land in Guatemala. In 2013, 8.4 percent of the world population controlled 83.3 percent of the world's wealth. In 2015, one search engine, Google, received 64 percent of search queries.

Why does this happen? Why do a few people, teams, and organizations enjoy the bulk of the rewards in life? To answer this question, let's consider an example from nature.

The Power of Accumulative Advantage

The Amazon rainforest is one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth. Scientists have cataloged approximately 16,000 different tree species in the Amazon. But despite this remarkable level of diversity, researchers have discovered that there are approximately 227 “hyperdominant” tree species that make up nearly half of the rainforest. Just 1.4 percent of tree species account for 50 percent of the trees in the Amazon.

But why?

Imagine two plants growing side by side. Each day they will compete for sunlight and soil. If one plant can grow just a little bit faster than the other, then it can stretch taller, catch more sunlight, and soak up more rain. The next day, this additional energy allows the plant to grow even more. This pattern continues until the stronger plant crowds the other out and takes the lion’s share of sunlight, soil, and nutrients.

From this advantageous position, the winning plant has a better ability to spread seeds and reproduce, which gives the species an even bigger footprint in the next generation. This process gets repeated again and again until the plants that are slightly better than the competition dominate the entire forest.

Scientists refer to this effect as “accumulative advantage.” What begins as a small advantage gets bigger over time. One plant only needs a slight edge in the beginning to crowd out the competition and take over the entire forest.

Winner-Take-All Effects

Something similar happens in our lives.

Like plants in the rainforest, humans are often competing for the same resources. Politicians compete for the same votes. Authors compete for the same spot at the top of the best-seller list. Athletes compete for the same gold medal. Companies compete for the same potential client. Television shows compete for the same hour of your attention.

The difference between these options can be razor thin, but the winners enjoy massively outsized rewards.

Imagine two women swimming in the Olympics. One of them might be 1/100th of a second faster than the other, but she gets all of the gold medal. Ten companies might pitch a potential client, but only one of them will win the project. You only need to be a little bit better than the competition to secure all of the reward. Or, perhaps you are applying for a new job. Two hundred candidates might compete for the same role, but being just slightly better than other candidates earns you the entire position.

ekhane nature bebohar korar ki dorkar chilo?

Very interesting!

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://jamesclear.com/the-1-percent-rule