Over the next several days, I'm going to share the complete text of the very first Ascension Epoch book we ever published. It's quite a bit different than what you probably expect after reading my introduction. There's no invading Martians or superheroes here; in fact, there's nothing paranormal at all. It has elements of Science Fiction and Alternate History, but it's really just about normal people in extraordinary situations.

This is a story about a family of refugees caught in the middle of man's cruelest pastime, war. And it's also about the man who has staked his life on protecting them. As I said, he has no supernatural talents to back him up. He's not a warrior or a conqueror. Hee doesn't possess the usual traits of the action hero. His trade is in saving lives, not taking them, but he is a hero nonetheless.

Since I notice there are a lot of libertarians on Steemit, I should probably mention that this one was written for a libertarian short fiction contest back in 2014, where it took second place.

Without further ado, I present to you the first chapter of House of Refuge.

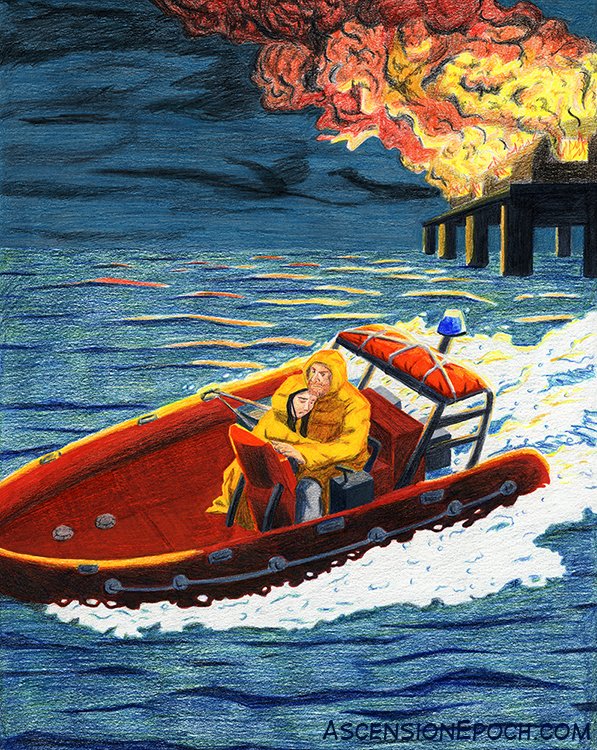

It was four o’clock in the morning when the electronic chime of the boat gong jolted Justin Agnarsson from his hard-won sleep. He blinked blearily at the flashing blue light on the overhead, wondering where and when he was and why he should not just roll over and go back to sleep. The scent of saltwater and the gentle pitching of his bed reminded him that he was on duty, and as stationkeeper he always would be. He slung himself off the mattress and began the mechanical motions of dressing while he watched the small monitor atop his bureau. The video feed from the well dock showed him the cause of the disturbance: a long hulled RHIB run up on the ramp and two stumbling figures in orange rain slicks tying a mooring line. A quick glance at the meteorological panel reported only light rain, a westerly wind of 17 knots and a wave height of only three feet.

‘Hardly shipwreck weather,’ he thought. He checked a second monitor for distress beacons, but there were none. It had been almost a month since anyone drifted to the refuge in need of assistance, and had it been the middle of the afternoon instead of the middle of the night, Agnarsson would have assumed it was a couple of old salts come aboard to share part of their catch and spin a yarn, and he’d have been grateful for the visit. At this hour, he had no idea what to expect. Out of habit, he took his sidearm off the bureau and holstered it, then finished dressing and ducked out the watertight hatch.

At the station store, he retrieved a medical kit, a gallon of fresh water, and a couple of thermal blankets. “Ahoy, lifeboat. How many souls aboard?” he called into the wall intercom.

He overheard muttering, snippets of a conversation in Spanish. Belatedly the answer came, a man’s voice, hoarse and tight. “Dos.”

He frowned. That lifeboat was easily big enough to hold a dozen people. When Agnarsson asked in his own inexpert Spanish if they carried any fatalities, the reply was negative.

Agnarsson climbed down two ladders to the well deck, eyeing the two bodies huddled against the bulkhead. There was a man, tall but stooped, with his arm draped across the back of a younger girl, who hugged her knees and stared sullenly out to sea. Agnarsson guessed that she was 15 or 16 years old. He could hear their hushed whispers punctuated by bursts of sobbing.

He crouched beside them, handing them the blankets and water. “Are either of you injured? Where are you from?”

They shook their heads to the first question and provided no ready answer to the second.

“Should I expect more boats?”

“Just us,” said the man. He was stout and barrel-chested, with a thick red beard and the deep tan of a mariner. Agnarsson judged that he was at least a decade his senior.

“Where did you come from?” the stationkeeper repeated.

“Our home. It burned,” the man answered haltingly.

“I’m sorry,” Agnarsson said blandly. These little tragedies happened often enough that his condolences began to sound rote; it was a hard life living on the sea, and seastead fires were especially common.

“Well, we have food, clothing, and bunks above deck. I’ll try to make you as comfortable as I can until we can get you to land or another vessel. Do you…” He hesitated. He was about to ask if their seastead was insured. There was no question about helping people adrift on the sea, no matter where they came from or what their financial condition was, of course, but houses of refuge like this one didn’t run on good feelings alone. Whatever the answer was, it could wait, he decided.

“Do you have any family or friends I can get in touch with? On shore or at sea?” he asked.

The other man’s glazed eyes flicked over him, stared through him. The girl wept.

Agnarsson nodded stiffly, brushed his hand through his short blond hair. “Let’s get something warm into your bellies, and then I’ll show you to your quarters. You can get changed and take a hot shower, whatever you need to do.”

“Thank you, sir,” the man said. Careworn lines around his eyes deepened as he asked, “Have you radioed about us yet?”

“Uh, no, not as yet. You caught me out of a dead sleep,” Agnarsson answered apologetically. “We’re supposed to have a crew of four, but right now this is a one-man operation.”

The castaway seemed encouraged by this news. “Please, sir, I have to speak with you before you make that report. It’s essential. Absolutely essential!”

Surprised by the man’s insistence, Agnarsson found himself nodding. “Very well. The report can wait until after breakfast.”

Agnarsson led his two guests into the galley and sat them down. As he rooted through the pantry, he wondered what the story would be, and whether he’d be offered a bribe for forgetting to make a report. Probably they did not have insurance and didn’t want to be hit with the bill for rescue. Or maybe they were smugglers, attacked by a rival crew, and they didn’t want any word of their survival getting out. Heaven knew there were enough smugglers and privateering operations in the 350-mile-long flotilla of seasteads and platforms known as the Plata Raft, a trade of misery and desperation fueled by the Brazilian-Argentine War. The grim situation ashore suggested other possibilities as well: maybe there was no seastead at all, and they were refugees or even escapees from a prison camp. Maybe they had escaped from the illicit traffic in human beings that still plied these waters. Agnarsson’s employer, Atlantic Littoral, rendered free assistance to war refugees and escaped slaves, but such people often preferred to keep a low profile, fearful of falling back into the clutches of their oppressors. Whatever the truth, the young stationkeeper prepared himself for a grim story. He brewed some coffee and loaded eggs, bacon, and instant potatoes into the AutoChef and returned to the table.

“Let me welcome you to South Atlantic House of Refuge Number 49, or Sweet Surcease, as we call her.” Mounted on the wall behind them there was an ancient piece of driftwood with that name burned into it, the work of the station’s first keeper more than twenty years ago. “My name is Justin Agnarsson. No need to stand on formality, just call me Justin if you like.”

“Thank you, sir. We are very grateful.” The man extended a calloused hand across the table. Agnarsson noticed that it trembled. “My name is Horacio Vietes. This is my daughter, Sandra.”

The dark-haired young woman stared unblinkingly at the floor and pulled tight the blanket wrapped around her, but said nothing.

“You wanted to speak with me before I made my report.”

Horacio Vietes hesitated, folding his hands and pressing them to his lips. At length, he replied with a question. “Is there any way you can see not to report this?”

The stationkeeper arched his brow as if in surprise, though he expected the request. “That would be highly irregular. I’m required to report all arrivals and all disasters at sea. Surely there are people who want to know that you and your daughter are alive?”

“That, sir, is the problem,” said Horacio. “I will be forthright, and leave the decision to your judgment. We were attacked by an Argentine warship. They boarded us without warning, and when I challenged them, they shot at us. My wife—” His voice grew strained again, and began to crack.

Agnarsson winced. There was no doubt what the man was about to say.

“My wife and my little boy were gunned down,” he ground out.

“On what cause were you boarded?”

“You will have to ask them,” he snapped, and his red eyes darted angrily. “I left Argentina fifteen years ago. We are not citizens, our home was not under its flag.”

“You moored in territorial waters?” Agnarsson asked.

“No. In the Raft, just as we are now.”

Agnarsson knew that both sides had made threats of interdicting vessels and seasteads in international waters, but this was the first he’d heard of any such action. If true, it was a dramatic escalation of the war. The Plata Raft, like all other high seas traffic, was guaranteed freedom from interference, and there were a lot of other flags flying on those vessels, flags of clades and states alike that would not quietly accept such aggression. It would risk the entry of other parties into the war, a war that was already going against the Argentines. There was only one reason that Agnarsson could think of for them to risk it.

“Mr. Vietes, I have to ask you something in my official capacity as an officer of Atlantic Littoral, and I expect an honest reply. But first, let me assure you that, no matter how you answer, you and your daughter are in no danger of being turned over to the Argentine navy. Houses of refuge are inviolable under the terms of the Treaty of Tokyo, as well as the Common Accords on Mediation, Extradition, Restitution, and Arbitration. As a matter of policy, Atlantic Littoral does not turn over the custody refugees or survivors at sea to hostile parties. Do you understand?”

“I understand.”

“Were you knowingly involved in piracy or privateering against Argentina, or smuggling of contraband?”

“Sir, you speak of treaties and the CAMERA accords, but they are just pieces of paper. What word do you give me man to man?”

Agnarsson straightened in his chair. “On my honor, I swear that I will live up to those terms, or else die failing to live up to them.”

Horacio gave a slow nod. “Yes. I helped deliver weapons and fuel to the Coloradan rebels. But my family had no part in it.”

“Your family had every part of it,” Sandra snarled. Her father shot her a sharp glance, but she didn’t heed it.

“I am proud to have aided the Colorados. We have nothing to feel guilty for. The Reconstructos weren’t satisfied just to murder grandfather and your brothers on land, they had to butcher Mama and Pedro, too. They are the guilty ones!”

“Be silent right now!”

“No!” She turned her fierce gaze on Agnarsson and spoke bitterly. “I don’t care if you call us pirates or smugglers. Unless they kill me first, I will do it all over again. And again, and again, until all the Reconstructo filth is washed from the earth! I will fight them with my last breath, and then may I die with my hands around their throats!”

Agnarsson would have been dismayed to hear those words from a grown man, much less an innocent in the early bloom of womanhood. He pitied her transformation almost as much as he pitied the loss of her family. Here was one of the tragedies of war that too often went unremarked, the outrages that transform the innocent into monsters and poison whole generations with hate.

“I am sorry for my daughter’s outburst. I implore you to forget her words.”

“I will not forget them,” said Sandra.

“I am sorry for all that happened to you. Regardless of anything else, firing on a woman and a child in their home is unconscionable,” Agnarsson said. “I must make my report, but I won’t mention anything you just told me. Not yet, anyway. For now I’ll report you as war refugees. That way you’ll have some help finding a place to live. Until then, you’ll be safe here.”

“Please! If you do, they will know where we are. They will come for us!”

“I doubt it. The whole world would come down on them.” The AutoChef buzzed, and Agnarsson stood up. “Try to eat something if you can, and then rest. You’ll be safe here.”