I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the twelfth installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5 | Ch 6 | Ch 7 | Ch 8 | Ch 9 | Ch 10 ] and every few days I'll post another chapter. From the back cover:

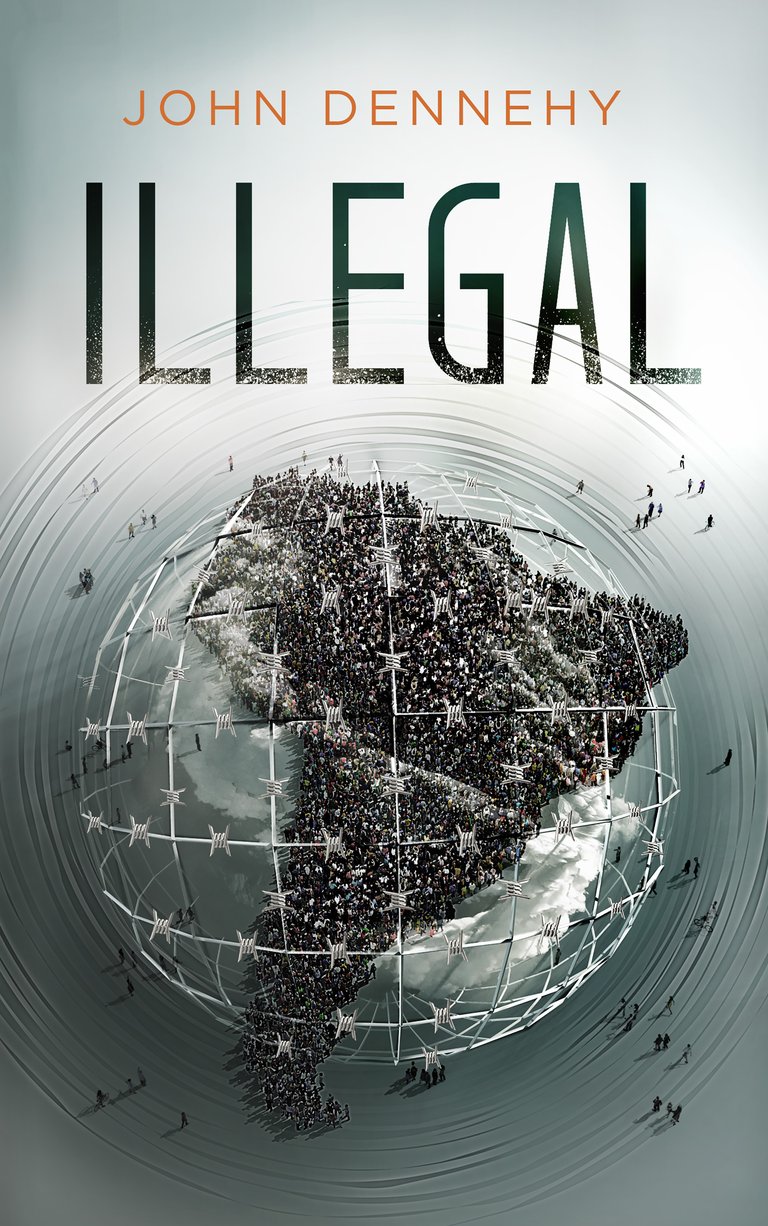

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

--

Crossing the Border with Lucia (2) [Chapter Eleven]

I was planning on returning to New York to attend my sister’s wedding in September, so a month before, in mid- August, I went to the Colombian border with Lucía to renew my visa. It was a month since she had moved to Latacunga and things were as good as they had ever been since she had told me about her husband.

A brisk five-minute walk separated the two immigration offices at the border crossing. Between the two offices there are about one thousand feet and one winding river. Río Carchi, the river that decides nations, cut a deep gorge through the soft bedrock on its long journey to the Atlantic Ocean. Rumichaca, as this crossing is named, is the only permanent link between the two nations—and it’s in the middle of nowhere. Tulcán, Ecuador, to the south, and Ipiales, Colombia, to the north, are separated by ten miles of rolling green hills. While the area boasts an elevation of nearly ten thousand feet, the mountains, while still impressive, are fairly gentle compared to other parts of the Andes.

During the day a steady stream of people cross the bridge and the traffic is roughly equal in both directions. The lines at immigration can become rather long, but that was usually due to the slothfulness of the officers rather than the volume of people passing through. Ecuadorians and Colombians vacationing in each other’s nation make up the bulk of those waiting in line to get their passport stamped. The locals from the border towns, at least those who cross daily, never stop at immigration. Each nation keeps their border control set back from the river, and thus it is easy enough to walk to the side of the building and get into a taxi. If these locals are questioned they flash their national ID with their local address and while technically still illegal, the police allow it. They are just crossing for a few hours, visiting friends or family, or more likely, going shopping. Although the two towns sit just ten miles apart, the prices of the same products varied widely because of government taxes and subsidies. In Ecuador gas was less than a dollar a liter and almost twice that in Colombia, but buying a pair of jeans in Colombia might save you a third of the price.

While the two towns bustled with people and goods traversing the two-lane concrete bridge, the actual crossing was the territory of a more sinister type of person. Unfortunately, I would soon become intimate with these border creatures.

When I renewed my visa I usually went to the border and returned quickly, but this time Lucía and I planned to make a weekend of it. Our two days in Colombia passed without incident, but I ran into trouble coming back into Ecuador. I was granted an exit visa in Colombia, and then walked across the bridge into Ecuador.

The police told me that I had been issued too many visas and they would not grant me a new one. It’s very possible that I could have just ended it there by sliding some money under the window, but I was new to the game and didn’t yet understand that immigration enforcement in Ecuador was undergoing a revolution just like everything else around it.

Confused, Lucía and I walked back across the bridge into Colombia to try my luck there. Colombia wouldn’t let me re-enter without the proper exit stamp from Ecuador. As I pleaded with the officer behind the counter, a small group formed to my side. When I left the window, half a dozen men, wearing jeans and T-shirts and with unshaven faces, approached me.

“Quiero ir a Ecuador—I’m trying to go to Ecuador, but they say I have reached my limit, and now—”

One of the men interrupted. “And now Colombia won’t let you in because you have no exit stamp.”

“That’s right,” I said.

“That’s a tough situation. Ecuador started enforcing some new laws a few weeks ago, making it tough for foreigners like you,” the first man said. “They say they’re old laws, but I’ve been here six years and I never heard of them.” He feigned sympathy. “But we can help you get your stamps. You just need a little bit of money. Everyone can be bought here—how much do you have?”

I glanced around, surprised that they were advising me to bribe the police so openly, and right next to immigration. At midday there would have been a hundred people waiting in line or standing around, but it was the end of the day and the outside waiting area, composed of polished tiles underneath a roof made of metal and clear plastic that hung fifteen feet above the ground, was mostly empty. I saw Lucía standing twenty feet away, talking to a tall, well-built Colombian police officer.

I entertained the idea briefly, but I wasn’t ready to do business with smugglers, or at least not yet. “I have to talk to my girlfriend. Excuse me.” I said and walked away.

I joined Lucía and her conversation already in progress. “Hello,” the officer said in a friendly voice as he extended his hand in greeting. His dark olive jacket was buttoned all the way up but you could still make out his matching tie underneath. He had three rows of service medals above his left breast pocket and the bright colors immediately gave me confidence that this was someone I could trust; someone I should listen to. He suggested we step inside his office to discuss my options and see how he might be able to help. I wondered if his motivations were any different from the group of men I’d just left, but a ranking officer’s uniform is a lot more convincing than the dirty clothes and faces of smugglers.

Our new police ally, Mr. Rodriguez, was the ranking officer at that late hour in the day—he was the one in charge. He led us inside the building to a well-kept corner office that looked onto the mountains in Ecuador through large, plate-glass windows. He had an expensive-looking desk that held a plaque with his name, an outdated computer, and a neat stack of folders. There were two cushioned seats in front of the desk and a larger plush chair that reclined and was tucked under the desk. A small TV sat on a table in the corner and the walls were filled with certificates and awards. Once we exchanged pleasantries and small talk, he got down to business.

“How much money do you have?”

The bluntness of it caught me off guard and my response was delayed. “About a hundred dollars,” I finally said.

“That’s not enough. I can get you your visa and free you of your troubles, but it won’t be cheap. If you want to set foot on the other side of this glass,” he said, pointing behind him, “if you want to return to Ecuador again, I need more money.”

I emptied my pockets and piled all of my cash onto the table. Lucía fished into her pockets and added to the pile of crumpled bills and assorted coins. We had $133.

Mr. Rodriguez eyed the pile and said, “I still need more. Do you have an ATM card? There’s a bank nearby and taxis outside.”

“Yes, I have a card, “I said, “but I have already used it today and can’t use it twice in the same day. My bank will reject it.” I lied, knowing that I had already offered a significant bribe.

Mr. Rodriguez looked at me, as if pondering the situation, then grinned. “I think $133 will just cover it,” he said as he pulled the pile toward him and counted the bills again.

He called his cousin, Eduardo, who had friends on the Ecuadorian side, and we waited. For an hour we drank coffee and traded small talk during commercial breaks of the telenovela that was playing on the TV.

When Eduardo finally arrived he looked like the coyotes (smugglers) I’d seen outside earlier which didn’t instill me with confidence. But there was one key difference: his cousin was a police captain. Still in the police office, Eduardo instructed me to give him $73 and keep $60 in my pocket to hand over to Ecuadorian police when he instructed me to. He led me to the bridge while Lucía waited with Mr. Rodriguez in Colombia. Because it was nearly 10:00 p.m. and the border was about to close for the night, there was not much international traffic, but anyone who was crossing could have plainly seen me hand a passport and wad of bills over to two smiling Ecuadorian police officers halfway across the bridge. The officers casually strolled back into Ecuador, leaving Eduardo and me to wait. A few minutes later, the two trudged back to the halfway point of the bridge and returned my passport with a new exit stamp. My passport now read that I exited Ecuador without ever entering it.

“But I need an entry stamp,” I said to Eduardo, confused.

“I know. Don’t worry,” he said. “The $60 you paid bought you the exit stamp, but the police also cleared your record. The next time you enter Ecuador you won’t have any problem with your visa limit because they erased everything. It will be as if you’re entering for the first time. Tomorrow morning you’ll be legal in Ecuador, drinking beers with that pretty girl of yours,” he said, slapping my back as if we were old friends. “Don’t worry about immigration in Colombia, just go straight to Ipilaes now and get some sleep. No one will stop you—and if they do you can always call me to get to my cousin so we can work something out.”

Lucía and I caught a taxi back into Ipiales for some rest and an ATM, thinking all our problems had been solved with the $133 we divided between the two nations.

The next day, after getting my stamps in Colombia, I was denied entry into Ecuador a second time. I called Eduardo and told him to come back to the border and figure it out for me. He came quickly, but was not very cooperative.

“I did my job, whatever happens now is your problem,” he told me flatly.

“Your job was to fix my passport. I paid you to get me back into Ecuador and they still won’t let me in.” I said, raising my voice.

Other smugglers, many of whom I had met the night before, came over to listen.

“You need to fix this,” I said to Eduardo, pushing my passport into his hands.

“I can’t help you,” he said, pushing my passport back and crossing his arms.

Another coyote stepped in. “All you have to do is slip a $20 bill into your passport before you slide it under the window in Ecuador.”

Frustrated and not sure what else I could do, I walked back over the bridge with Lucía. Less than twenty-four hours earlier I had walked away from these same coyotes, thinking my morals were higher than theirs, but when it came down to it and my back was against the wall, I gobbled up their advice and thanked them for their help.

Ecuador was a long lesson in my hypothetical ideals smashing against a much crueler and more complex reality, but I only ever saw that in hindsight.

Immigration into Ecuador is located two hundred feet beyond the bridge on the right side. We joined the long line and waited. I made a last second decision to try and get the stamp without a bribe, but was denied for the third time. When I protested, the heavyset officer on the other side of the glass told me he’d seen me in there earlier and would personally see that I was arrested if I tried to go through again. He pointed to a sign behind him listing all sorts of offenses and claimed that I was illegal in his country. As I walked away, I could hear him repeating his threat, “Three to five years. You will rot in jail for three to five years if I catch you in here again.” Not really what I was hoping for.

I had gotten my first peek inside an Ecuadorian prison three weeks earlier. A few blocks from my house in Latacunga the police allowed you partway inside to drop off and pick up laundry that inmates or their wives washed. South American jails were interesting because they were different but also especially scary for the same reason. Ana once told me about a time she was at a party that the police broke up. They found marijuana on a few people and though Ana never smoked, drank, nor had any paraphernalia on her possession, she was rounded up with the others and sat in jail for fifteen days before being released. She was never charged, never got a phone call or lawyer, she just sat in an overcrowded prison for two weeks never knowing exactly why she was even there. Ecuadorian jails are severely overcrowded and underfunded so the guards rely on the inmates to self-police. In some prisons, cells are rented by the police so that initially everyone is left to fend for themselves in open spaces and courtyards that police do not patrol. I always pushed the thought away that I risked ending up there, but the idea hung over me. In the brief moments that broke through the veneer a wave a fear would flash through me.

By this time most of the smugglers who hung around Rumichaca knew my story. Many of them changed money, sold coffee, or otherwise were working the border, but I soon learned that they all made their real money as coyotes. When I walked out of the office, one man offered to change my dollars to Colombian pesos but quickly recognized me and asked how it went. He shook his head when I told him I tried to go through without a bribe. “That’s why they were so upset. A twenty will do it no problem.”

I put a crisp $20 bill in my passport and waited for an officer, any officer to pass by outside. With the smuggler looking on approvingly, I stopped the next man I saw in uniform and slipped him the cash and passport. “I’ll see what I can do,” he said before disappearing inside.

Lucía and I sat down on the ground, leaned our backs against the building’s wall and waited. Nothing. Half an hour passed and nothing. Then, we watched as the overweight officer with an attitude walked by holding my passport and made some photocopies of its first page before going back inside. He looked at me and gave a wicked smile. “Shit, this is bad,” I thought. The same guy who seemed hell-bent on arresting me knows that I disregarded his threat and tried to bribe someone else. I became convinced that I was destined to enter Ecuador in handcuffs before this was all over.

Quickly, I gave Lucía a copy of my passport and told her to go to the U.S. Embassy if anything happened. I was desperate for help anyway I could get it, but was also vaguely aware that this, seeking help from the U.S. Embassy, was an example of the unequal power relations between my native country and my adopted home. I was using my inherited privilege. In the grand scheme, I opposed this power structure which made my life and wounds somehow more important than that of others, simply by place of birth, yet when pressed I also used it. And that’s the power of it and an illustration of how hard it will be to dismantle. Few people will give up power or privilege voluntarily, rather they will find ways to rationalize it and, ultimately, entrench that structure by doing so. I was no different.

Lucía and I spent the next few minutes brainstorming lawyers and politicians who might be able to help if I did manage to get myself into an Ecuadorian jail that afternoon. I wrote her a note and my parents’ email addresses and instructed her to send the message as an email if I was taken away. It said that everything was fine and I was looking forward to the wedding. I didn’t want them to worry.

“Baby, I’ll push to get the divorce faster,” Lucía said. “If we were married you wouldn’t have to worry anymore.”

We had casually discussed this recently but never in much depth. Up until then a trip every ninety days was more an excuse to satisfy my wanderlust than a burden. My first job in Cuenca was the only one that ever offered me a visa. Both ESPE and UTC knew my status and encouraged me to continue my border crossing work-around. “We’ve never gotten a work visa for an independent foreign teacher before and frankly would not know where to start,” they each told me.

Then there was Lucía’s marriage. She had already filed for divorce but was technically still married.

Next to the main immigration building was a much smaller office that sat in front of and to the left of immigration, forming what would have been a corner if not for the narrow hallway that ran between the two. We sat down against the wall in the midday sun with a view of immigration’s front doors. We held each other tight, worried that it might not last.

Finally, a third officer came out, gave me back my passport—minus the $20—and told me that if I even set foot on Ecuadorian soil again, I would go straight to jail. That was the last time I ever tried to bribe border police in Ecuador.

Lucía and I gladly retreated to Colombia, but that created a different problem. After getting the entry then exit stamps from Colombia that morning, I was illegal in that nation as well. But we had no choice. We walked back into Colombia and caught a taxi into Ipiales, blending into the flow of locals who passed back and forth without stamps.

I realized by this point that Mr. Rodriguez was not an honorable man, but no one on his side of the border had yet threatened me with jail, and I took a lot of comfort in that. Plus, Colombia, in addition to cocaine trafficking and civil war, was also the kidnapping capital of the world and had the largest refugee population of any nation on Earth. Thus, Ecuador maintained strict border control, trying to keep Colombia’s problems from spilling over, but there were no regular checkpoints on the Colombian side—contraband and people were leaving Columbia, not entering. It was getting late and we needed a break to clear our heads. Lucía and I decided to grab dinner, get a hotel, and try crossing again in the morning.

I was stuck in this nation-less stalemate, illegal on either side of the river, for almost a week. I walked back and forth over that same two-lane bridge close to fifty times that week, and each time was unique. I walked across with police, with Lucía, with soldiers, with smugglers, alone, thinking that I would soon be in jail, thinking that I would finally be legal, and sometimes, thinking nothing at all.

That week I earned an education in borders.

I sat playing cards or having idle conversation with the money changers and other men who worked the crossing. They would check their watches often and periodically point to an approaching truck.

“See that brown truck coming toward us?” one of them asked me.

“Yeah.”

“Watch it. The police won’t check it.” He smiled. “That one’s mine.”

“What’s in it?” I asked.

“Cocaine,” he answered. “It all ends up in your country, but sometimes it’s safer to ship it from Ecuador so we bring it across here.”

“Is that the only thing you smuggle?” I asked.

“No, we can get anything across. A lot of cocaine crosses here but sometimes the trucks have guns. FARC keeps a lot of weapons in Ecuador.”

FARC was especially active in the border region between Ecuador and Colombia at the time. The government controlled the official crossing but much of the nearby borderlands were rebel territory. The guerillas kept some supplies across the border within Ecuador because they felt they were safer from detection there.

As an afterthought, the smuggler added, “For the right price I can put you on one of those trucks, get you wherever you want to go.”

“Yeah right, just like Eduardo. No thanks, I’ll figure something out.” I told him.

While I was stuck between nations, Colombia’s civil war and cocaine trade moved freely between them. The theory of borders was beginning to reveal itself as the opposite of the reality. The window screen was keeping me out while making rich men of drug smugglers, arms dealers, and corrupt police.

I was so grateful to have Lucía. Having her next to me, holding her hand, made it bearable, at times even humorous. Unsure what to do or who we could trust, we went to the Ecuadorian consulate in Ipalies, Colombia and explained my situation. The first day they didn’t have any answers, but we found out that the secretary was from Ambato and grew up in the same neighborhood Lucía had been living in. They became friends and the next day, the secretary introduced us to another woman. Lucía found common interests and made small talk for half an hour before she casually asked what could be done for me. Finally, after a week stuck at the border, and with Lucía working her people skills, I was granted a special transit visa from the consulate.

“I’m traveling to the United States for my sister’s wedding next month. Will I be able to return?” I asked.

“Yes, your girlfriend told me about that,” she said. “Things have been crazy here the last few weeks and they are making things harder for you, but this should fix everything and give you a clean record. You won’t have any problems coming back.”

I joked with Lucía that I would write a book about the experience and call it Cruzando la Frontera con Lucía—Crossing the Border with Lucía. I had no idea that my week of being stuck between nations was just the beginning, a sort of introduction to the next year of my life.

--

The ebook will be FREE tomorrow (16 Oct) all day on Amazon if you want to download it. And for those interested in where we are, here is the Table of Contents

thank you very much

wow. loved the scene when you bribed the police in colombia. was like a scene from a movie

I like the symbolism you create through the story, it makes it more atmospheric

Cheers! Symbolism is a big part of the work, hanging out in the background. You can download the whole ebook for free on Amazon today if you're interested. Today only. https://www.amazon.com/Illegal-Story-Revolution-Crossing-Borders-ebook/dp/B074FYB6V7/

@johndennehy intetresting love story somewhere sad. Thanks for sharing

Thank you for using Resteem & Voting Bot @allaz Your post will be min. 10+ resteemed with over 13000+ followers & min. 25+ Upvote Different account (5000+ Steem Power).

You got a 35.18% upvote from @postpromoter courtesy of @johndennehy!

Want to promote your posts too? Check out the Steem Bot Tracker websitevote for @yabapmatt for witness! for more info. If you would like to support the development of @postpromoter and the bot tracker please

What an intriguing story,really interesting. Thanks for sharing @johndennehy @

Every story which is related to cross border makes me emotional

Hi @johndennehy!

Your UA account score is currently 1.604 which ranks you at #33527 across all Steem accounts.

Your rank has dropped 51 places in the last three days (old rank 33476).Your post was upvoted by @steem-ua, new Steem dApp, using UserAuthority for algorithmic post curation!

In our last Algorithmic Curation Round, consisting of 312 contributions, your post is ranked at #234.

Evaluation of your UA score:

Feel free to join our @steem-ua Discord server

Please help this Blue Baby Patient, Laine Kharece by upvoting the link below. This is not a scam, we just need your support as part of steemit community. Thank you very much for reading and extending a little help.

https://steemit.com/upfundme/@wews/steemit-help-a-blue-baby-patient

Please help this Blue Baby Patient, Laine Kharece by upvoting the link below. This is not a scam, we just need your support as part of steemit community. Thank you very much for reading and extending a little help.

https://steemit.com/upfundme/@wews/steemit-help-a-blue-baby-patient

Your post was mentioned in the Steemit Hit Parade in the following category:Congratulations @johndennehy!

thanks for this post