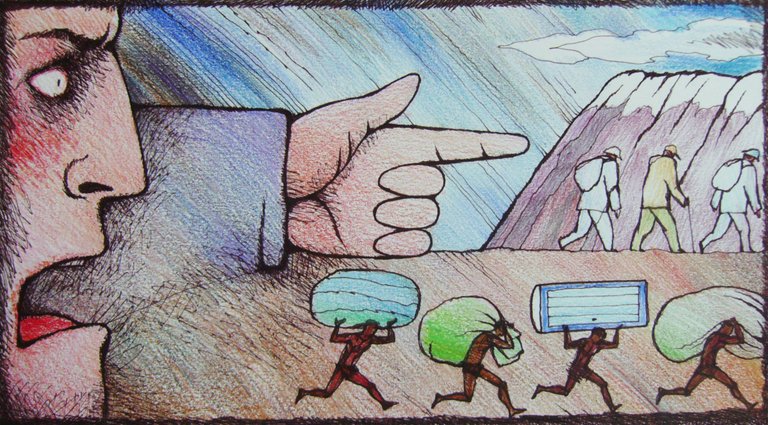

…we made a touchdown at eight thousand feet to begin with. Chugunkov covered his dark hair with a sun hat, put on sunglasses and a dark grey sports suite that was expensive even to look at. His appearance had something in it of a drug lord who had arrived into the jungle for a personal inspection visit. He charged right ahead. His solemn entourage was trundling forlornly behind: two security guys, two subordinate businessmen he had kidnapped to keep him company, and a couple of tour guides at the front and in the rear. If you don’t count the security and the local tribesmen carrying the stuff, I was the poorest of the lot. But Chugunkov still believed that my connections at the unions would rain his vengeance down upon the contractors who had screwed him over, and so I was invited to come along. I didn’t hold out much hope for Unite’s legal teeth, and so I thought Africa would be a nice last place to visit. I had never been in the mountains, and here we go – twenty thousand feet…

So, eight thousand feet for starters. I was quite obviously not up to the tempo, having been foolish enough to listen to Chugunkov (who was a typical billionaire and cared deeply for his health) and having joined him in taking two magazine loads of vaccine shots – from haemorrhagic fever all the way to, and including, the bubonic plague. Even though the hipster at the clinic had assured me that modern vaccines do not contain actual viruses, but only their genetic code, that code was plenty enough to do me in. Vivacious Chugunkov got away with a slight upset. As for me, I’ve only started so much as walking upright literally a day before the flight – and even that was done on principle: I had understood that kicking the bucket while still in the capital would have forever consigned my name to the mountaineering book of shame. It was only upon arrival that the experienced guides explained to me that vaccines are a matter of taste and faith: the chances of catching something with an immune system shell-shocked by vaccines are about the same as those for an unvaccinated, but a steady one. The most important thing was lack of oxygen – breathing in and getting no air. I was feeling like I had been hanged and was being dragged on the noose to put the fear of God into the others. African jungles… “they are so cute from a reasonable distance” – Melman the Giraffe from Madagascar knew what he was talking about.

My salvation came, as these things do, at the moment immediately preceding my death. I was hugging some baobab and drooling profusely, having run out of strength and material for vomit. As I was considering the next baobab in the distance as the place where I shall decide again between going on and dying, I became suddenly aware that I was not alone. The person standing above me was Sanjeet – a stereotypical jagged looking dark brown Indian with a pitch black beard and ebony eyes. I kept thinking he was wearing a turban even though it was just another sun hat.

– “Slowly”, Sanjeet was saying, “go slowly. You go very quickly, then rest. Wrong. Go slowly, but don’t stop. Let’s try. No. Very quickly. One step for two seconds. Okay?”

I put my fingers into an OK gesture; Sanjeet did likewise. I didn’t know at the time that he was a diving instructor too, and that he had been serving in Afghanistan in what must have been Dr Watson’s regiment. I was going in what felt like a slow motion film. That was unbearable at first, but then I realised that I could survive that. We still had four hours of jungle track before the break. It took me a while to realise that it was raining.

It gets cold in the mountains at night, even if it’s baking hot during the day. I dragged myself into the tent, curled up into a foetal position and tried to fall asleep. “Shit doesn’t catch a cold, always lie down on your stomach; then it’s fine even in the snow” – echoed a memory of Iqaluk Rodgers, my Alaskan border guard friend from the Cold War times.

Some serious swearing was shaking the air over Mount Kilimanjaro. The client-centred Africans had finally erected mobile phone masts in boot camps, and so there was reception along most of the route. Chugunkov discovered that his building site had received wrong diameter funnels, and the locals at the camp were now absorbing Tolstoy’s powerful, flexible, precise and eloquent language. The locals were sitting around a gas stove with their African heads slightly askew. Some mysterious brew was bubbling in the cauldron on the stove – the tribesmen were cooking dinner.

Chugunkov was howling and dashing around like a voodoo priest.

– “Taking radio style!.. Radio style!! Shut up! I talk, you listen – radio!!! What do you mean sixteen?!! The pressure is thirty two!! In your ass!!! Thirty! Two! Why the fuck are you silent there?! Talk! Radio, fuck it!!! Over!!! Mother!.. Fuckers!..”

That rap was the background to me sinking into sleep, which was weighing down on me like a cold swamp. The tent turned into a submarine that was running out of air. A bubbling nightmare flushed over me. The Faculty of Arts and Humanities introduced a mandatory mathematics course that was examined at the local school, and there was no way I could avoid it this time round. I was walking like a prisoner into the secondary education hell with my head held low. The grey pavement stones, the walls painted dirty blue, the inexterminable and inseparable smells from the canteen and the shitter. I lingered at the entrance to the classroom and held a chubby hand up.

– “Late?” – Mrs Grossel was not amused – “Only trouble with these students, no discipline at all. Sit down. Examination paper B.”

– “Erm… preparation time…” – I squeaked.

– “You should be fully prepared by your daily work” – beamed the Grossel – “my dear students, this is your last chance to rectify your situation…”

I squeezed myself behind the desk. Shabby planks were pressing on me. But from the depth of my psyche, from the boiling red core of the planet, a primordial rage was rising up. Why am I actually tagging along here? How old am I? Has this happened before? So it cannot happen again? And if it does happen again, would I now get myself into that?! I tore upwards through the sticky nightmare, not being fully aware of what was going on, and threw the desk aside.

– “Fuck! You! To fucking hell!!!” – I yelled as I was shaking off the dream. The car suddenly braked and I was pushed forward. Some time passed as I was staring into space with my eyes dazed and wide open, like those of an infant child. The guys were taking guns out of a sports bag at their feet and slamming the bolts. I stuffed a Browning into the side pocket of my leather jacket. No problem. As I was getting out of the car, I got tangled up in the slippery side of the tent and went down on my back, unable to breathe. There was no air. Sticky acidic sweat was dripping off me. I curled up into a foetal position again. I was in fever.

The camp was waking up. Africans were bubbling something in their languages, Europeans were caterwauling in theirs, Russians were coughing their curses out. The sun was painting the tent in acid colours. I would have slept a while longer, but for the sharp string of a full bladder. Altitude sickness, the high barfy, is similar in symptoms to heavy hangover from a week of drinking. Cramps, nausea, and a pound of broken glass in your head – just like my good old primary school days, except for the smelly breath. The way to the shitter was a torture. Surprisingly enough, you can’t just piss under a baobab in the African jungle – each camp has one or two stationary bogs and a few mobile ones in purpose-made tents. In the morning, the tribesman packing up the camp puts a portaloo on his head and gets going, dancing up to the next camp in 6-8 hours.

Back at the tents, I spotted Fraser. The old Scotsman was looking like a crow that was stupid enough to join a flock of migratory geese and just about made it to the first stopover. He was indignantly cleaning his feathers. Back in the real world, he had climbed all his mountains a long time ago and presently had a business that was almost Buddhist in that it was based on the principle of inaction. Fraser was a mediator: he was earning wodges of cash by settling problems in courts and city councils, and was sipping Irn-Bru in one of his cafes in his spare time. In the meantime, the courts were meting out justice and the bureaucrats were going through their unknowable regulatory mazes. When the stars aligned into any kind of acceptable solution, Fraser was getting a bonus. When they didn't, he was getting more money for overcoming the adversary's resistance. Chugunkov was calling that "confirmation bias peddling", but paid up anyway – he had a longing for miracles in his life. Miracles were mostly delivered, and so the old Scotsman's remaining wish was to never see mountains again. But the irrepressible Chugunkov kept dragging him along. Fraser could not refuse. He was angry and jaundiced, but he kept going...

Continued in the next part. Subscribe if you want to read more.