The Human Species, where do we come from and what is "Natural" about "Human Nature"?

The development of human beings and their capacity for language and culture

Humans belong to order of primates, the suborder Anthropoidea (higher primates), the superfamily Hominoidea (hominoids), the family hominidea, the subfamily homininae (hominins), and the genus Homo (true humans) and the species homo sapiens sapiens (which means, literally, wise wise man).

All these terms might seem unnecessarily complicated, but these classifications help us to understand where we "fit in" as far as other animals are concerned and, particularly, what makes us truly human and thus able to develop a sophisticated means of communication (language) and complex sociocultural systems:

- Primates: One of several kinds of mammals (animals who suckle or nurse their young and have body hair). Besides humans, the class of primates include lemurs, lorises, tarsiers, monkeys and apes.

- Anthropoidea (Anthropoids): So-called "higher primates", which includes monkeys, apes and humans (the "lower primates" or Prosimii includes the lemurs, lorises and tarsiers).

- Hominoidea (Hominoids): Includes humans and apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans and gibbons).

- Hominidae (hominids): Humans and their ancestors and possibly African apes. Some scientists have suggested that African apes - chimpanzees and gorillas - should also be included here because of their close relationship to humans and that humans should be distinguished from them in a separate subfamily, hominins.

- Homininae (Hominins): Humans and their ancestors.

Homo - True humans (genus)

sapiens sapiens - The wise, the wise (species)

Associated with these classifications, and for our purposes of this post, almost more importantly, are certain specific characteristics. While considering the early development of human beings and their capacity for language and culture, the characteristics that we share with other animals, such as primates, hominoids etc - all the way through to our more truly human (genus and species) features - are significant.

Briefly, and because they belong to these various classifications, human beings possess the following meaningful characteristics:

- Primates: They live in social groups and are active during the day; their behavioural patterns are diverse and flexible; they have an expanded brain capacity and keen vision (and rely less on smell); the young have a relatively long period of growth and development (and hence time to learn the behaviours of their group); have dexterous hands; teeth for a varied (not specialised) diet; the skull and skeleton protect the internal organs.

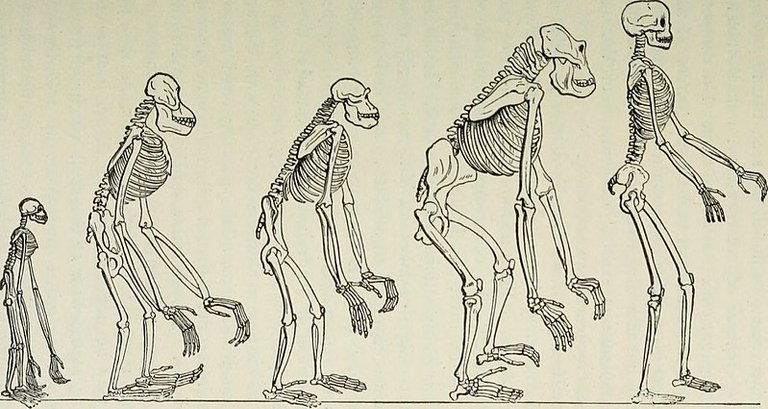

- Hominoids: In addition to broad shoulders, absent tail and long arms, distinctly human characteristics such as bipedalism (walking on two legs) and culture are more pronounced.

- Hominids: Further increase in brain size and complexity, further development of bipedalism and upright posture - leaving the hands free to carry things and alter the environment.

- Hominins/Homo sapiens sapiens: Although there is still some scientific debate as to whether both hominids and/or (only) hominins are the exclusive classificatory domain of humans, this is where living human and their (now extinct) ancestors belong. The fossil record gives a good idea as to how the genus Homo (true humans) developed from the early excavated examples such as Australopithecus africanus (identified by Raymond Dart at Taung, Northern Cape in 1924) to the modern humans of today.

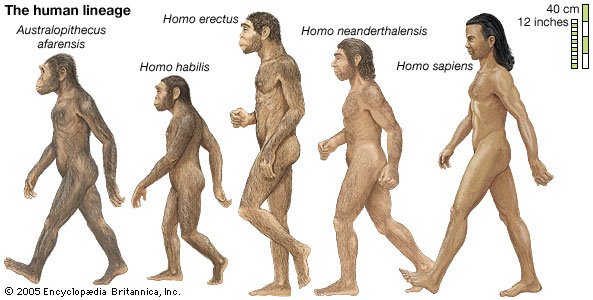

The hominid line is approximately 4 to 5 million years old. It originated with Australopithecus afarensis, emerged and, in the midpoint of its over a million years of prehistory, this species apparently began using pebble tools to process meat.

Some two million years ago, this species began to disappear, and four others appear to have replaced it. Two were still australopithecines, "southern apes", but two belonged to the genus Homo: Homo habilis and Homo erectus. The "ape" forms were exceedingly robust and probably were grazing herd animals dominated and protected by formidably big males. The "human" forms had larger brains and, in the case of Homo erectus, a highly developed toolkit and, possibly, fire. The latter definitely had home bases or camps of piled stone or bushes. Male Homo erectus hunted game; females probably gathered vegetable foods to bring to the common camp. This is a basic pattern for our species, as we shall see. Homo erectus outlived its three companion species by nearly a million years. But it in turn quickly disappeared with the appearance of a new, highly successful species.

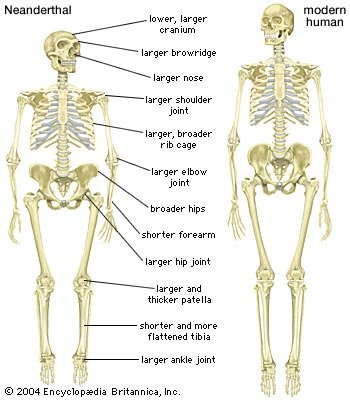

Starting around 200 000 years ago our own species, Homo sapiens, began to appear in archaic form. By 50 000 to 40 000 years ago, fully modern humans beings had appeared, displacing a closely related species, Homo neanderthalensis. These species are associated with remarkable toolkit of fine projectile points, and they both hunted big-game animals by hurling spears. Both exploited a new ecological niche, that of big-game hunting in cold and warm climates. But only one, Homo spaiens sapiens, was capable of speech.

Primate behaviour thus provides a platform for the emergence of humanity. That is, we emerged from a species of highly intelligent species, all capable of hunting and using tools. Australopithecus africanus is associated with Oldowan tools during its period in prehistory. Homo habilis definitely used them, as did Homo erectus. The latter is associated with fine Acheulian tools. In contrast, the robust australopithecines were not habitual tool users. The trait of tool making culminates in Homo sapiens's truly magnificent Solutrean tools, finely shaped projectile points.

We assume, then, with justifiable certainty that human culture is based on prehuman primate prototypes. However, at some point Homo sapiens developed speech and a language. Speech consists of the ability to distinguish phonemes (speech sounds), meaningless elementary units of sound, from each other in our speech tract or system, and to combine these into morphemes, the smallest meaningful elements or units (words or part of words). We further combine the morphemes into words, or sentences, according to the rules of grammar. Speech is genetically dependent on our large brains, and on our vocal chords.

Speech is thus a language, a set of messages that govern how human systems go about processing matter and energy to maintain themselves, and, eventually, their species. The distinctive features of Homo sapiens include not only speech but associated communicative traits facilitated by speech. These include marriage and the family, expressed in speech through name-given roles as distinct from persons, upheld by normative rules such as incest taboo, a universal prohibition among all human populations. These features also include rituals surrounding the transformations of yearly and lifetime cycles. These traits were first given expression in a community pattern derived from the primate troop: the human hunting-gathering band.

"Human Nature"

By studying human nature, the variety of societies in the world today and in the past, and the relationship of the human species to others, we are better able to understand why we behave the way we do. The physical anthropologist gives us valuable information about the uniqueness and limitations of our physical structure. Why are we different from apes, for example? It is important to know the ramifications of being able to walk with erect posture on two feet, rather than having to use our hands to steady ourselves. It means that we have our hands free to use for other things, such as making tools. Having a thumb opposite the fingers rather than in line with them means that we can grasp and manipulate tools and use them to our advantage, as weapons or as precision instruments. The physical anthropologist has also contributed to our understanding of another factor of crucial importance in the process of becoming human, namely, the origin of language. We know that only humans have the capacity for speech, not only because of our vocal apparatus, but also because of the size and structure of our brains. By providing answers to the question of what makes human beings unique among animals, physical anthropology gives us the first clues in understanding human behaviour.

It tells us what the basis for that behaviour is, and what the limitations upon it are. It tells us why we should expect others to behave within those limitations, and what variations are possible. In other words, physical anthropology teaches us what no matter how much diversity we might find in the world around us, the most remarkable fact is not how different people are but how similar they are, and this is a crucial lesson in getting along in the world today. Anthropologists currently are careful not to make simplistic generalisations about "human nature". There was a time when a kind of pseudo-science was practised with reference to "human nature". It tended to regard human natures as unchangeable and even characteristic of a particular group of people - and everything from differences in suicide rates to kinds of mental illness and thought patterns and even apparent intellectual abilities were ascribed to the "human nature" of a particular group rather than to sociocultural, contextual and historical variables.

Images are linked to their sources in their description and references are stated below.

References of Authors and Texts Titles:

Moore.A : 1992 - Cultural Anthropology. The field of human beings, San Diego: Collegiate Press

Friedl.J 1976 - Cultural Anthropology, New York: Harpers College

Thank you for reading

Thank you @foundation for this amazing SteemSTEM gif

I love the second part of your post @Zest. The following statement reminds me so much of eugenics

All the best to you :)

Hi @abigail-dantes. I do apologize for the delay in replying to this comment.

First post of yours I've read. I enjoyed it. Made you some SBD but not a lot of discussion here and no replies from you. This looks like botland.

I have strong opinions about anthropoid stuff and would love to get a discussion going. IMHO what is called human "nature" is human delusion caused by the inability to separate abstraction from reality, the apparent nail in the coffin and the evolutionary dead end of the homo lineage.

I also think we should stop trying to isolate what makes humans different from other life forms and instead concentrate on what makes us similar. Human exceptionalism is the type of human "nature" that will delete us from the roster of life forms.

Get back to men if you feel like discussing. Thanks.

Hi @citizenzero. I would firstly like to thank you sincerely for the comment and support. It is truly appreciated.

In my above post I have tried to explain how we are not very different to other species within our lineage but what makes us unique as a species is our ability to communicate and manipulate the world around us to our advantage and also how we as a species are not different from each other but rather very similar in a number of aspects but it is our culture that differs:)

I would also like to invite you to please join the SteemSTEM chatroom.

https://steemit.chat/channel/steemSTEM

Thanks for the invite. I've been on Steemit chat before but somehow can't get back in because my posting key doesn't work any longer. Just haven't gotten around to changing it.

I love anthropology and your articles are very scholarly; like a text book. I'm more of a rabble-rouser. I want people to think a bit differently than they always have, to open up their minds to new ideas. Sometimes I'll post outrageous things to stir the pot a bit. But I do appreciate what science believes are the truths it has uncovered so far. That makes for a good launch pad. Good work.

Please do try your best to sort out your issues with respect to logging into steemit chat This following statement of yours is truly what I love to do as well :

It would be an absolute pleasure and adventure to chat to you:)

Thank you so much:)

Got a new password and logged on today but no time to chat. Hope to be in contact soon. Cheers.

Very cool article

nice!

Very cool article. I like the way you've written it here, it makes the ideas seem more credible.

Thank you!

fascinating to read about the species that is the most common to us, but we (I) know so little about! Thanks for the article and I am looking forward to your next post

Much appreciated @samve. Thank you!!!

Thank you for another interesting read! Was there evidence that the development of speech/language led to (or at least coincided) with a lengthening of the lifespans of Homo-sapiens? Since we're social creatures (most of us) that tend to have better physical and mental health (as long as we're in a stable and healthy setting) in a group, was there an indication of it being so for the first developing Homo-sapiens?

Thank you!