Think wisely.

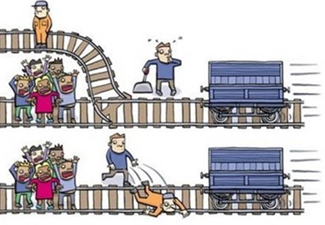

There is a train that is approaching at high speed on one track and is out of control. This is directed towards five workers who are on the road. You cannot warn them and you cannot stop the train either, but you can activate a lever that will divert you to another route. There is another worker there, but he is alone, so the other five will be saved.

Would you change the needles knowing what is the result of your decision?

We are before two possible answers: press the button and save five people in exchange for the death of one, or not to press the button, with which the five people will die, saving the one that is in the other way. If we activate the button there is no doubt that we save five people, a greater number of lives, but along the way a person will have died with our decision. How is a life measured? Can you measure? Is there a correct answer? All a moral dilemma that, most likely, although you have it clear, you will doubt.

Source

If you think that saving five people is the best option in this case, you will agree with most people: 90% say they would change the needles. However, imagine that you are facing a situation equivalent to the previous one, but now instead of changing the needles you have to push a very fat person to stop the tram with his body. That person will also die without remedy, but the other five will be saved. Would he push her?

Although again it is about saving five people at the expense of one, this time only 25% of people say it would give the fatal push: killing is not the same as letting die; that is what our moral perceptions tell us. What if the one in the dead way is his father? What if it's your son? Would you sacrifice them to save five people? Intuition dictates that we do not have to change needles. What if he is an unknown child?

The scientific work indicates that our morality has evolved to favor cooperation and it seems that in this way mechanisms have been favored that make us choose intuitive decisions that are not always those that offer better objective results.

In the study of morality, those who favor those good decisions are those that achieve the greatest benefit for the greatest number of people are qualified as consequentialists. Those who focus on rights and duties, who think that certain decisions, like throwing a man from a bridge, are never good even if they seek a greater good, are called deontologists. The fact that most people tend to prefer this second approach indicates that these moral norms have been favored by natural selection.

Source

We are facing a mental experiment initiated and devised by the British philosopher Philippa Foot and later adapted by Judith Jarvis Thomson in 1985. Foot was especially critical of consequentialism, that is, that phrase we have heard many times that says the end justifies the means; that when a final goal is important enough, any means to achieve it is valid. Philippa then devised the dilemma of the train, a recipe to enter fully into the discussion; can it really be justified to kill one person to save others?

Another dilemma: the doctor's choice

Both Thompson and other philosophers have provided other variations on the same train dilemma or even in other more frightening scenarios. Let's see.

Source

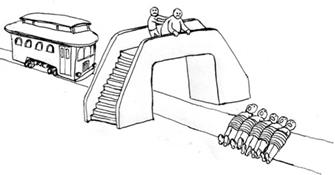

You are a doctor and you have five patients who need immediate transplants to live. Two require a lung, another two a kidney and the fifth a heart. There is an adjacent room where another individual recovers from a fracture in the leg, but apart from this injury, the individual is in perfect condition. Therefore, if we kill the healthy patient and take their organs we could save the other five, what would you do?

It is possible that our thinking is quite clear that this is a murder, without more, but it does not stop having the same result as the first dilemma that seemed so easy to answer when we started.

So, is there a correct answer to these dilemmas?

Considering all the dilemmas it seems that they all have the same consequence, however most people would only be willing to press the button of the first dilemma. Very few would throw the fat person on the road, much less kill that poor patient to give their organs to five others. So?

The truth is that there is no right answer and will depend on a large number of factors. As Foot explained, it is possible that the human being has a scale where there is a distinction between killing and letting die. While the first is active, the second is passive.

What is clear, whatever you choose, is that this dilemma and similar thought experiments to evaluate people's ethics show that most people approve of some actions that cause harm, while other actions with the same result are considered inadmissible. This happens every day without us noticing and even agreeing on some of the actions, it is possible that among us vary the justification to act like this. They are the dilemmas of the real world with which we have to deal with each day.

Thank you for reading.

For more information, visit the following links: