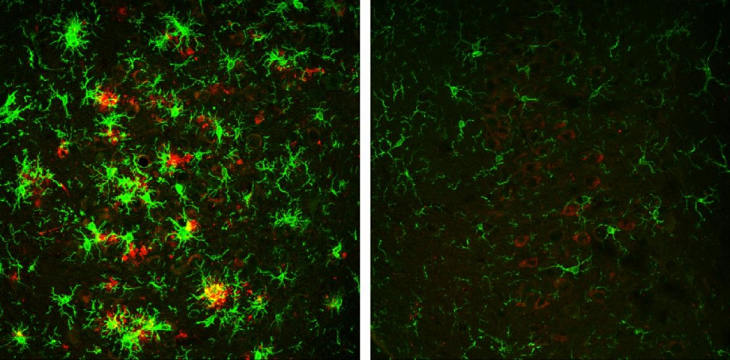

The formation of amyloid plague in the brains of mice having Alzheimer’s disease is reversed, when enzyme beta-secretase, also known as BACE1 is gradually depleted, thus improving the mice’s cognitive function.

Credit: Hu et al., 2018

The brain of a 10-month-old mouse with Alzheimer's disease (left) is full of amyloid plaques (red) surrounded by activated microglial cells (green). But these hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease are reversed in animals that have gradually lost the BACE1 enzyme (right).

This is according to findings of a study by researchers from Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute, US., published on February 14th, in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

According to the researchers, there are high chances now, that drugs that target this particular enzyme beta-secretase, will be able to effectively treat Alzheimer disease in humans.

a) What is amyloid-β peptide (Aβ)?

Specific causes of Alzheimer disease remain unknown, however many factors are recognized to be causative agents, including the anomalous aggregation of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), responsible for the formation of amyloid or neuritic plagues in the brain.

It is this neuritic plagues that interfere with the function of neuronal synapses, and are considered pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer disease.

b) What is BACE1?

BACE1, also known as beta-secretase, significantly contributes to the production of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) by cleaving amyloid Precursor protein (APP).

Inhibiting BACE1 therefore serves to inhibit the formation of amyloid plagues. According to the researchers, drugs that inhibit BACE1 are potential treatment options for Alzheimer disease.

On the flip side however, BACE1 controls several other vital process as it cleaves to proteins besides APP, meaning that these drugs could equally pose several serious side effects.

Following from the study, it was found that mice that completely lacked BACE1 suffered severe neurodevelopmental defects.

However the effect of inhibiting BACE1 in adults when further investigated in mice that gradually lost the BACE1 enzyme as they grew older, gave promising results: normal development of the mice was observed, with the mice remaining healthy thereafter.

When however these were bred with rodents that developed amyloid plagues and consequently Alzheimer disease at the age of 75 days, resulting offspring equally formed plaques at this age, despite their BACE1 levels being averagely 50% lower than normal.

c) Positive signs as BACE1 gradually decrease

Encouragingly nonetheless, the resultant plaques were noticed to start disappearing as the mice grew older and lost BACE1 activity. Indeed, at 10 months old, the mice were found to have no more plaques in their brains.

According to Yan, this observation of a gradual reversal of amyloid deposition is the first of its kind.

"To our knowledge, this is the first observation of such a dramatic reversal of amyloid deposition in any study of Alzheimer's disease mouse models," he said.

d) Other effects of decrease in BACE1

Additionally, decreasing BACE1 activity led to lower levels of beta-amyloid peptide, furthermore reversing other hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease, including the activation of microglial cells as well as the formation of abnormal neuronal processes.

The learning memory of mice with Alzheimer's disease, was also improved y the loss in BACE1, although upon electrophysiological recordings of neurons, it turned out that the depletion of BACE1 only partly restored synaptic function.

It might therefore appear that BACE1 could be necessary for optimal synaptic activity, including cognition.

e) Conclusion

The study provides genetic evidence that preformed amyloid deposition can be completely reversed after sequential and increased deletion of BACE1 in the adult, according to Yan, the vice chair of neuroscience with the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute.

"Our data show that BACE1 inhibitors have the potential to treat Alzheimer's disease patients without unwanted toxicity.

Future studies should develop strategies to minimize the synaptic impairments arising from significant inhibition of BACE1 to achieve maximal and optimal benefits for Alzheimer's patients," he concluded.

Of course it remains to be seen whether such improvements demonstrated by lab mice will also translate to human beings.

"We've been able to cure Alzheimer's disease many, many times in mice, but still haven't done so in humans," Hendrix noted, as reported by Dennis Thomson, in the Chicago Tribune .

Even so, this is a positive leap in the right direction in the struggle to find treatment for Alzheimer's disease.

This new study was published Feb. 14 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.