HOW TO READ HIEROGLHYPS

CHAPTER II

The reading of hieroglyphs

Reconnecting to the previous post, I would like to continue with the intention of teaching you some basic rules on reading hieroglyphics.

I state that mine will be a practical and quick guide on how to read the most common signs, but I will not give any notion of grammar, at least, not in this series of articles; this is because the grammar of the Egyptian language (which, as you have seen in the previous article, has gone through various evolutionary phases over the centuries) is not at all easy, even for those who have a training in classical languages.

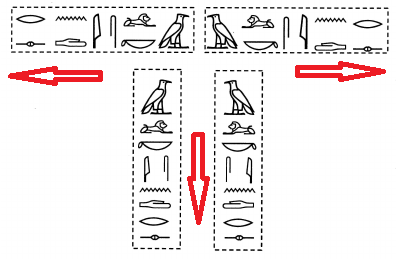

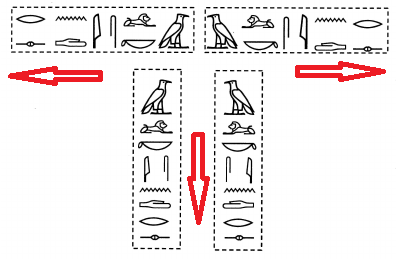

Hieroglyphics can be read in multiple ways depending on the orientation of the signs; this orientation is determined by the direction in which an animal or a person turns their gaze; in a horizontal line if the hieroglyphs are facing left the reading goes from left to right, vice versa if they look to the right. They are not only written horizontally, but also vertically, in this case the reading proceeds from the top down.

.png)

Figure 1 credits: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Horizontally-and-vertically-written-hieroglyphics-Aleksan-dros_fig4_259608629

Hieroglyphics are divided into three categories:

• The phonograms; in turn subdivided into uniliterals, biliterals and triliterals

• Phonetic complement; a phonogram, usually a uniliteral, which has no phonetic value, but is a "clue" that tells us that the adjacent hieroglyph (a bi or a trilitteral) contains within it the letter represented by the uniliteral.

• Determiners; a series of hieroglyphics without any kind of phonetic value that is found at the end of one or more hieroglyphics, indicating the semantic field of the represented word. In the absence of vowels, the proposed words are often repeated, the only way to avoid confusion between the various similar terms is precisely to use an unambiguous determinative that indicates that the word means "animal" rather than "bowl".

Believe me, the practice is much simpler than the theory and, above all, the exercise is the only valid method to learn to read them and to distinguish phonograms from phonetic complements or determinatives.

For anyone wishing to continue studying grammar more deeply, I highly recommend consulting the Allen and Gardiner manuals. In addition, I recommend Alan Gardiner's "The list of signs", easily available on the internet, which lists all the most famous hieroglyphics divided into categories.

Let's begin:

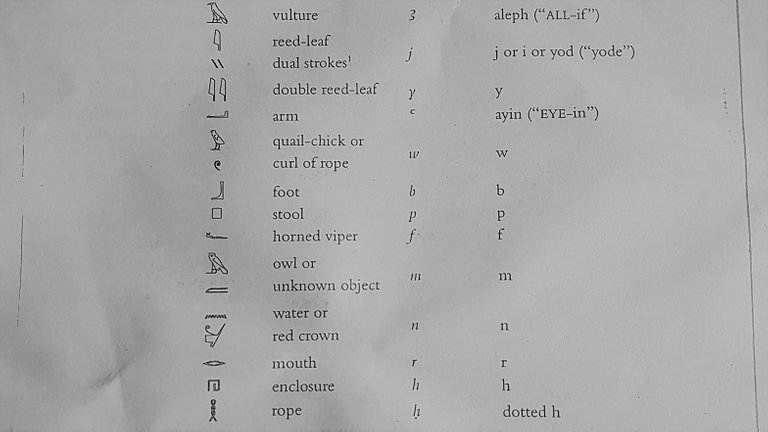

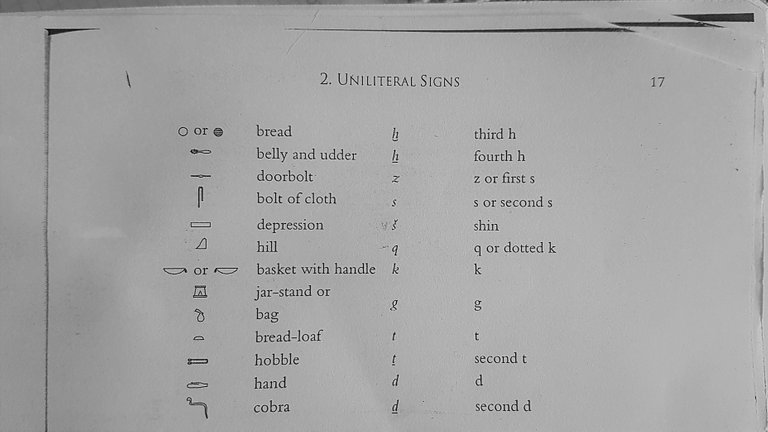

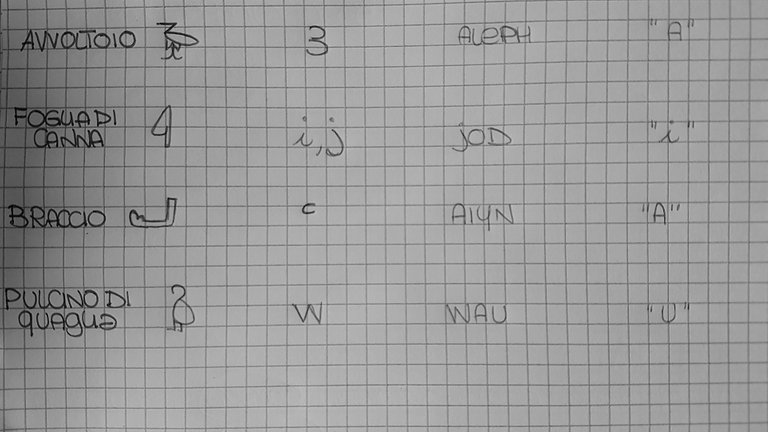

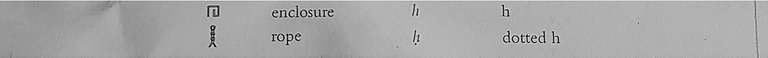

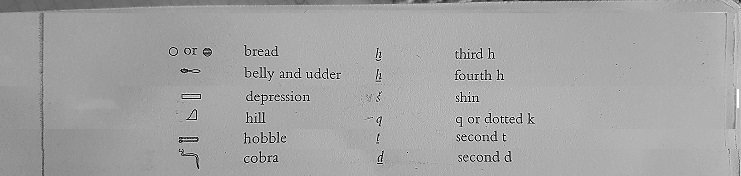

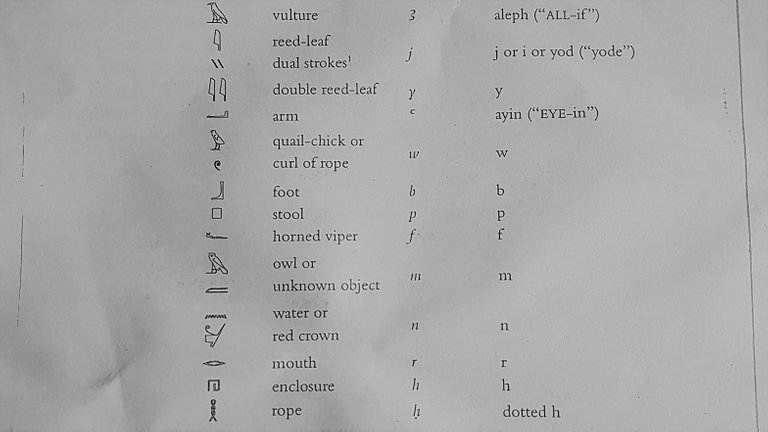

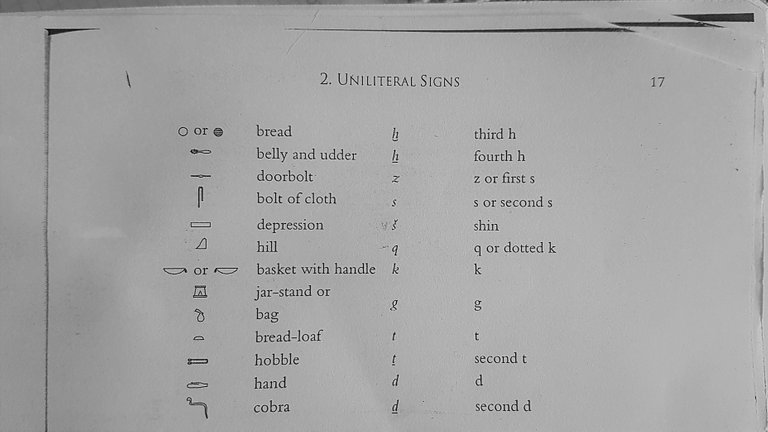

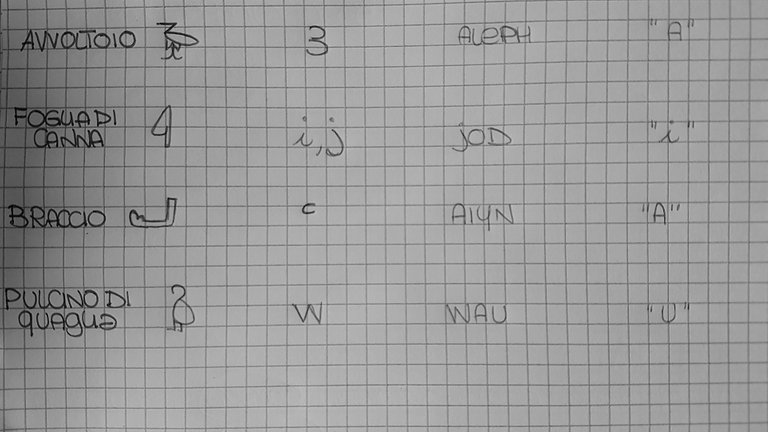

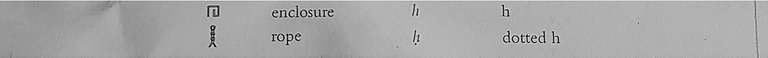

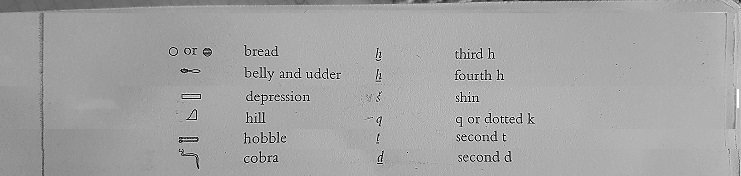

As already mentioned, the simplest hieroglyphics are the uniliterals, they, as the name implies, are composed of a hieroglyph and only one, which has a "sound". The uniliterals can be used together to form a word, or close to other hieroglyphics to indicate the phonetic value of one of its parts. In all, there are 30, inside we find semivocal (or rather semiconsoning), which can be reductively compared to our vowels; these are Alef, Ain and Waw.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Figure 2: Uniliterals table from the Allan’s Egyptian Grammar.

To help you understand this table I will explain what you find inside it; on the left side you have the uniliteral followed by what it represents (for example, the vulture is the first), then in the central column you find the phonetic transliteration of the sound and the last column shows the name of the hieroglyph (the pronunciations are given in brackets ; aleph, for example, is pronounced "alif").

Excluding the more complex letters, which I will explain below, the most common ones like "m", "n", for example, are read exactly as in our alphabet.

These are those that are called "semivocal", Aleph and Ayin are translated with apparently strange symbols, but can be read with "a". As well as Yod and Wau who, with the appropriate quotation marks, would represent our "i" and "u"

Each hieroglyph is transliterated into a letter of the western alphabet to be made readable, but there are also some signs, called diacritics, which linguists use to indicate the exact pronunciation of a sound. Thus for example ḫ and ẖ are pronounced differently, even though for us they are often so faint sounds, that they do not belong to our language, that we cannot pronounce the exact differences

They will then be read as follows:

• h: like our h.

• ḥ: it is an aspirated h

• ḫ and ẖ: they are difficult sounds for some, in a simplistic way you can read both as "ch".

• Š, called "shin": it can be read as "shi"

• ḳ: is our "q"

• ṯ: pronounced "tj"

• ḏ: pronounced "dj"

Therefore, given the absence of vowels in the Egyptian system, every time two or more consonants will come together, between them, to make reading easier, we will insert an "e": for example the word "home", transliterated " pr "si read "per ".

In the case in which instead, among the consonants a semivocal appears (Aleph, Iod, Aiyn or Wau), they will be read as real vowels without the addition of "e"; for example "bull", transliterated "k3" reads "ka". <br

COME LEGGERE I GEROGLIFICI

CAPITOLO II

La lettura dei geroglifici

Ricollegandomi al post precedente, vorrei continuare nell’intento di insegnarvi qualche regola base sulla lettura dei geroglifici.

Premetto che la mia sarà una guida pratica e veloce su come si leggano i segni più comuni, ma non darò alcuna nozione di grammatica, almeno, non in questa serie di articoli; questo perché la grammatica della lingua egiziana (che, come avete potuto constatare nell’articolo precedente, ha attraversato varie fasi evolutive nei secoli) non è per niente facile, anche per coloro che hanno una formazione nelle lingue classiche.

I geroglifici possono essere letti in più modi a seconda dell’orientamento dei segni; questo orientamento è determinato dal verso in cui un animale o una persona voltano lo sguardo; in una riga orizzontale se i geroglifici sono rivolti verso sinistra la lettura va da sinistra a destra, viceversa se guardano verso destra. Non sono solo scritti orizzontalmente, ma anche verticalmente, in questo caso la lettura procede dall’alto verso il basso.

.png)

Figure 1 credits: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Horizontally-and-vertically-written-hieroglyphics-Aleksan-dros_fig4_259608629

I geroglifici si dividono in tre categorie:

• I fonogrammi; a loro volta suddivisi in monolitteri, bilitteri e trilitteri

• Complemento fonetico; un fonogramma, di solito un monolittero, che non possiede alcun valore fonetico, ma è un “indizio” che ci dice che il geroglifico adiacente (un bilittero o un trilittero) contiene al suo interno la lettera rappresentata dal monolittero.

• Determinativi; una serie di geroglifici senza alcun tipo di valore fonetico che si trova alla fine di uno o più geroglifici, atto ad indicare il campo semantico della parola rappresentata. In assenza di vocali, spesso le parole proposte si ripetono, l’unico modo per evitare confusione tra i vari termini simili è proprio quello di utilizzare un determinativo inequivocabile che indichi che quella parola voglia dire “animale” piuttosto che “ciotola”. .

Credetemi, la pratica è molto più semplice della teoria e, soprattutto, l’esercizio è l’unico metodo valido per imparare a leggerli e distinguere i fonogrammi dai complementi fonetici o dai determinativi.

Un’aggiunta molto importante sono gli strumenti; per tutti i neofiti che vogliono avvicinarsi alla lettura dei geroglifici consiglio due pratiche guide per iniziare, entrambe sono in italiano, cosa molto rara, perché la maggior parte dei volumi più prestigiosi e attendibili sono in inglese o in tedesco.

• Geroglifici Egizi, manuale per imparare da soli, Collier e Manley, Giunti edizioni.

• La lingua dell’antico Egitto, Ciampini, HOEPLI

Per chiunque volesse continuare ad approfondire lo studio della grammatica, consiglio vivamente di consultare questi volumi. In aggiunta consiglio “La lista dei segni” di Alan Gardiner, facilmente reperibile su internet, in cui sono elencati tutti i geroglifici più famosi divisi per categorie.

Iniziamo:

Come già detto, i geroglifici più semplici sono i monolitteri, essi, come dice il nome, sono composti da un geroglifico e uno soltanto, che possiede un “suono”. I monolitteri possono essere usati insieme tra di loro a formare una parola, oppure vicino ad altri geroglifici per indicare il valore fonetico di una delle sue parti. In tutto sono 30, al suo interno vi troviamo delle semivocali (o meglio semiconsonanti), che possono essere riduttivamente paragonate alle nostre vocali; queste sono Alef, Ain e Waw.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Figure 2: Tabella dei monolitteri tratta dalla Grammatica egiziana di Allan.

Per aiutarvi nella comprensione di questa tabella vi spiego che cosa ci trovate al suo interno; nella parte sinistra avete il monolittero seguito da ciò che rappresenta (Il primo, ad esempio è l’avvoltoio), successivamente nella colonna centrale trovate la traslitterazione fonetica del suono e l’ultima colonna riporta il nome del geroglifico (tra parentesi sono riportate le pronunce; aleph, ad esempio, si pronuncia “alif”).

Esclusi le lettere più complesse, che vi spiegherò di seguito, quelle più comuni come “m”, “n”, ad esempio, si leggono esattamente come nel nostro alfabeto.

Queste sono quelle che si definiscono “semivocali”, Aleph e Ayin vengono transliterate con simboli all’apparenza strani, ma possono essere lette con “a”. Così come Yod e Wau che rappresenterebbero, con le opportune virgolette, le nostre “i” e “u”

Ogni geroglifico viene traslitterato in una lettera dell’alfabeto occidentale per essere reso leggibile, ma vi compaiono anche alcuni segni, detti diacritici, che i linguisti utilizzano per indicare l’esatta pronuncia di un suono. Così ad esempio ḫ e ẖ si pronunciano diversamente, anche se spesso per noi sono suoni talmente labili, che non appartengono alla nostra lingua, che non riusciamo a pronunciare le esatte differenze.

Verranno quindi lette così:

• h: come la nostra h.

• ḥ: è un’ h aspirata

• ḫ e ẖ: sono suoni difficili per noi italiani, in maniera semplicistica si possono leggere entrambi come “ch”.

• Š, detta “shin”: si può leggere come “sh” di piscina

• ḳ: è la nostra “q”

• ṯ: si pronuncia “tj”

• ḏ: si pronuncia “dj”

Quindi, visto l’assenza di vocali nel sistema egiziani, ogni qual volta si incontreranno due o più consonanti vicini, tra di loro, per rendere più agevole la lettura, interporremo una “e”: per esempio la parola “casa”, traslitterata “pr” si leggere “per”.

Nel caso in cui invece, tra le consonanti comparisse una semivocale (Aleph, Iod, Ayin o Wau), esse si leggeranno come vere e proprie vocali senza l’aggiunta di “e”; per esempio “toro”, traslitterato “k3” si legge “ka”.

Fonti:

James Peter Allen, Middle Egyptian: an introduction to the language and the culture of Hieroglyphs, Cambridge, University Press, 2010

Nicolas Grimal, A history of Ancient Egypt, Wiley, 1994

Maria Carmela Betrò, Geroglifici, Verona, Mondadori, 1995

Ciampini Emanuele, La lingua dell’Antico Egitto, Milano, Hoepli, 2018

Alan Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar; Being an introduction to the study of Hieroglyphs, Oxford, Griffith Institute, 1957

Foto:

Immagine 1

Le immagini non citate, sono realizzate da me.

Questo post è stato condiviso e votato dal team di curatori di discovery-it.

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here

Congratulations @maryincryptoland! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPVote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

This post has been voted on by the SteemSTEM curation team and voting trail. It is elligible for support from @curie.

If you appreciate the work we are doing, then consider supporting our witness stem.witness. Additional witness support to the curie witness would be appreciated as well.

For additional information please join us on the SteemSTEM discord and to get to know the rest of the community!