.jpeg) image source

image source

When a child first takes a pencil, he does not try to draw a recognizable object. What happens is that you try to have fun with the movement of the pencil and with the signs or marks that arise from the movement of the pencil. These marks are known as "squiggles" and often, adults try to assign meanings or concrete forms. The truth, says DJ Hargreaves in his book Childhood and artistic education , is that the adult can not recognize what the child does because not even the child, at first, recognizes what is "scribbling". Little by little, they discover that other people expect these scribbles to represent something.

"It may also happen that, by chance, the child's scribble actually looks like a person, a fish or a dog and he realizes this happy accident."

Over time this is changing and the scribbles begin to transform step by step.

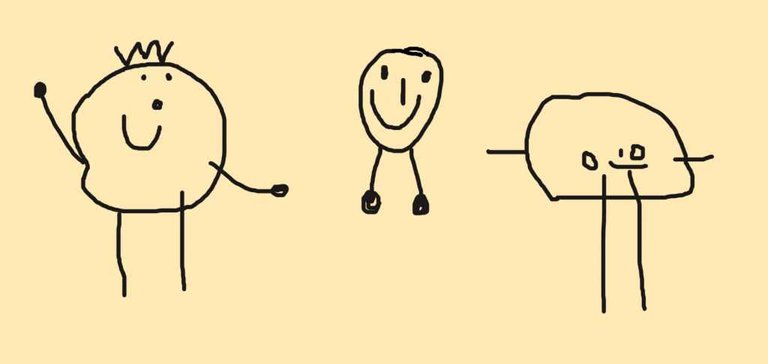

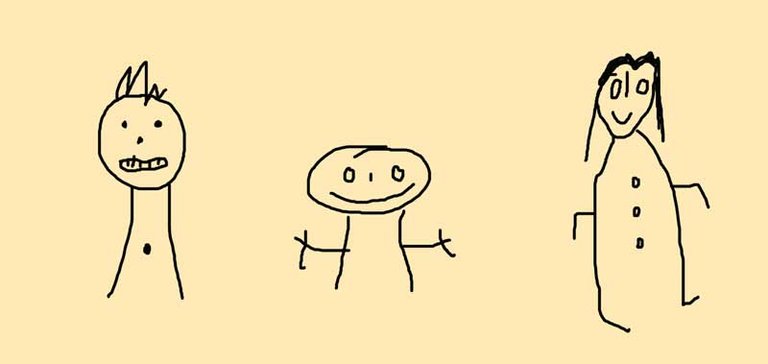

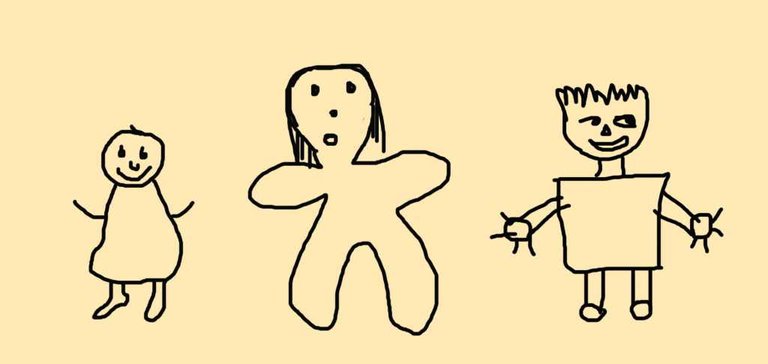

One of the first drawings that children deliberately try to make are the drawings of people, but these, in turn, have particularities. The author of the book explains that human beings are complex and therefore, their pictorial representation is also complex. At 3 years of age, children's attempts to represent human figures are quite peculiar; They are called tadpole figures (tadpoles) and almost all children draw them. The particular thing about tadpoles is the absence of parts and "some characteristic aspects are inserted in a rather strange way," says the author. The most striking feature of the tadpoles is the absence of the torso and the presence of arms that join the head. There are also figures of "transition",

Childhood and artistic education (The tadpoles have a unique closed surface that usually contains facial features, the arms are often omitted but if they are drawn, they are stuck to the closed surface).

Childhood and artistic education (in the transitional figures the bodily features such as arms, navel and buttons appear in the lower part of the figure).

Childhood and artistic education (conventional figures usually have independent closed surfaces that represent the trunk and head, sometimes the figure presents a single closed surface).

But why do children make bodies without torso or "tadpoles"?

Hargreaves says there are quite a few interpretations. In one of these it is thought that young children have an incomplete mental image of the human body, an image in which they omit the torso. It is also believed that in fact they can have a complete image, but that they simply limit themselves to drawing those parts of the body that seem most significant to them. Another fact that rescues the author is that children examine the objects following a vertical axis from top to bottom and also draw the human body following that same order. Based on this, there is evidence related to the memory that indicates that there is a tendency to correctly remember the first and last elements of a list, even if those in the middle are forgotten.

"When drawing, the child must not only remember all the parts of the body," says Hargreaves, "But must do it in the proper order; it also has to satisfy other requirements, such as the way in which each part should be drawn and the way in which the parts are to be composed ".

What does all this mean?

.jpeg) image source

image source

That it is normal to expect these demands to draw a human body, include omissions and that the torso, which is located right in the middle, is the best element to be forgotten.

Other researchers agree that the child's body image is complete, but also believe that the torso in the tadpole is included in the drawing. In relation to this, it is explained that young children do not segment the body image in as detailed parts as larger children or adults do. In that sense, the total silhouette of the tadpole may include the entire mass of the figure (head and body) to which the arms and legs will be joined. Also, the torso may be located under the "head" and between the "legs" of the figure.

But not all tadpoles mean the same thing.

For some children, lack of body is associated with effectively ensuring they can not draw a body. Others, on the other hand, affirm that their drawings do have a body and in fact they can say, exactly, where is said body. According to some studies, most children are able to identify their "torso" in one way or another, this goes hand in hand with the idea that the tadpoles do indeed have torso, although the parts are not different.

"For most children, the closed surface represents both the head and the body of the figure," explains the author of the book. "This means that, when children join arms to this closed contour, their figure is not as strange as it seems at first sight; the arms are not always attached to the head, but to the body, "he adds.

There is something important in this information and it is that this lack of differentiation between head and body can not always be associated with the perception or understanding that the child has about the human figure. They are very capable of identifying the head and torso of a person and the scarce differentiation is only given in the graphic representation. Another important point is that all children live the "tadpole" stage at different times. For some, this stage is very short and for others, it can be extended for months. The most key is to understand that children do not stay forever at that point and step by step, so they see their surroundings and other elements, they develop a much more conventional body type.

All this and much more is what nursery teachers and educators learn during their formative years, which further highlights the importance of their work and its impact on training processes. They have the tools to respect the processes and encourage the development of all children in this and other important aspects of learning.

Dear friend, you do not appear to be following @wafrica. Follow @wafrica to get a valuable upvote on your quality post!