Theologians may quarrel, but the mystics of the world speak the same language.

– Meister Eckhart

We live in unexemplary times, maddened by fear, murderous ignorance, and mistrust of one another. Even though Muslims make up around a fourth of the global population, or around two billion souls, for many, the faith has become besmirched with backwardness and violence. Islamophobia is a widespread, too painful reality, and hate speech is not without its cost. It is a proven fact that hate crimes against Muslims are on the rise, from bullying in the classroom to racial slurs, as well as more grave offenses, such as mosque burnings, even murders. Which is to say, hate and violence (on either side) begin in minds and hearts before finding their way to our lips and, soon enough, translating into heinous actions against (oftentimes, dehumanized) Others.

As an immigrant, Muslim, and writer living in Trump’s alarming America, as well as a citizen of our increasingly polarized world, I will not deny that speaking out on behalf of Islam has become something of a burden and sweet responsibility. I find that I must begin most conversations on this subject, including this one, by stating the obvious: “Terrorism has no religion and most victims of terrorism are moderate Muslims.”

It’s tiresome to be continually on the defensive, which does not always bring out the best in us or the most charitable, gentle responses. A German Muslim scholar, when asked about the connection between terrorism and Islam, went on this rant:

Who started the first world war? Not Muslims. Who killed 6 million Jews in the Holocaust? Not Muslims. Who killed about 20 million Aborigines in Australia? Not Muslims. Who sent the nuclear bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Not Muslims. Who killed more than 100 million Indians in North America? Not Muslims. Who killed more than 50 million Indians in South America? Not Muslims. Who took about 180 million African Muslims as slaves obliged them to leave Islam, 88% of whom died and were thrown overboard into the Atlantic Ocean? Not Muslims . . .

Which is not to say that I believe, as a Muslim community, we are entirely off the hook either. I agree with many theologians and scholars of Islam who call for profound self-examination and a better understanding of the faith, such as Hamza Yusuf’s formula for “a renovation of the abode of Islam . . . to make new again, repair, reinvigorate, refresh, revive our personal faith.” It seems self-defeating and willful to deny that something is rotten within the Muslim community, and that we need serious housekeeping.

As I said, we must begin, of course, by declaring to ourselves and the world in no uncertain terms, Not in Our Name, This Violence. There is a damning quote, by Canadian author Robertson Davies, that sums up how I feel about so-called “religious” fanatics in a handful of words: Fanaticism is overcompensation for doubt. To distance ourselves from the blasphemous-murders-who-would-sabotage-faith, we need to embody the peace, love, forgiveness, and sacrifice we find in the spirituality that sustains us, and extend it to those who do not know any better.

For those who wish to throw out the luminous baby, Faith, with the sordid water of current events, it is wise to recall the timeless words of a religiously inspired proponent of nonviolence, the great Martin Luther King Jr.:

Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that.

Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.

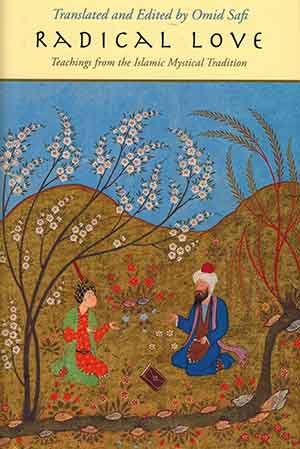

Meantime, for those who wish to deepen their understanding of the Muslim faith and its ecstatic dimension, I recommend Omid Safi’s Radical Love: Teachings from the Islamic Mystic Tradition (Yale University Press, 2018) as a fine point of entry. A leading scholar of Islam, Safi’s Radical Love arrives on the troubled scene with a peace offering, to clear the good name of a much-maligned, widely misunderstood religion. Showing Love to be at the very essence of Islam, the Divine, and, by extension, everything in existence, Safi’s stirring collection of excerpts then goes on to expertly illustrate how grossly terrorists (in the news and political office) have misperceived the faith.

Which is to say, in the scorching heat of public debate on whether all Muslims are dangerous and should be banned from the civilized world, this book serves as an oasis. Safi presents us with a cool spot to sit and reflect on a religiously inspired state of bliss that, of necessity, precludes violence. After all, in honoring Beauty—as the Quran does, unmistakably, by declaring that God is beautiful and loves beauty—we learn to better appreciate the sanctity of life, all life, and recognize violence, any violence, as the cowardice, failure of imagination, and heresy that it truly is (irrespective of who tries to manipulate which holy text to suit their devious ends).

It is remarkable, for example, during this historical moment of Islamophobic panic, that a thirteenth-century Sufi mystic, Mawlana Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhi (known as Rumi in the West), is not only a best-selling poet but the most popular poet in the US! This is doubly interesting, since Rumi was also a refugee who lived in a turbulent time of religious persecution, not entirely dissimilar from our own. For the millions who appreciate Rumi’s poetry, Safi’s anthology offers an opportunity to better understand the Arabic/Persian traditions that produced him as well as the Muslim holy book, the Quran, that is fertile soil for Rumi’s soul and art.

After all, isn’t it another form of (insidious?) Islamophobia, given Rumi’s current stature in popular culture, that the appreciation of his art should come at the expense of erasure of Islam from his work—as though this beloved, mystical poet is only palatable to the masses if entirely dissociated from the seeming stain of Islam?

Safi’s own translations, here, seek to rectify this subtle violence, by making clear the ongoing conversation with Islam, or love letter addressed to the Divine, that inspires Rumi’s poetry:

The mystics of Islam see themselves as being rooted unambiguously in the word of God . . . their poems and stories are “Qur’an-ful,” filled with both direct and indirect references to scripture.

Selections from the holy Quran are featured in Safi’s Radical Love alongside sacred sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (Hadith Qudsi), emphasizing self-knowledge and mercy as a counterbalance, one hopes, to the ugliness and ignorance that blaspheme in the name of Faith:

The remembrance of God

brings serenity

to hearts. – Qur’an 13:28

To know God

intimately

intimately know yourself

“He who knows his own soul

knows his Lord” – Hadith Qudsi

Also featured in this fine spiritual compendium are mystical utterances and teachings of Divine love by celebrated Sufi poets, such as Attar, Hafez, and other key Muslim mystics, carefully selected and translated by Safi.

Page after page, we encounter these “intimates of God” (awliya’, in Arabic) all love-drunk, engaged in the alchemy of transformation and advocating the hard work of overcoming ego and seeking Divine intimacy:

Love of a human being

is an ascension

toward love of God. – Ruzbehan Baqli

My heart takes on every form

a pasture for gazelles,

a cloister for monks,

the idol’s temple . . .

I follow the religion of Love:

Whichever way this caravan turns,

I turn. – Ibn ‘Arabi

Before reviewing this book, I had just completed another rather intriguing book on Islamic mysticism, entitled Ahmad Al Ghazali, Remembrance, and the Metaphysics of Love (2016), by Joseph E. B. Lumbard. The titular mystic, Ahmad, whose life and work are under study in this radical book, was the younger brother of Abu Hamid Muhammad Ghazali, regarded by many as the most important Muslim theologian.

Yet, according to both Lumbard and Safi, the path of radical love in Islamic mysticism found its most articulate spokesman in the lesser-known Ghazali, whose “Sawanih” (a short meditative prose text) Safi refers to as “the love child of Platonic dialogues and Shakespearean sonnets in a Persian Garden.”

All this beginningless and endless love, naturally, circles back to the Divine, who is quoted in Safi’s book as saying:

I was a Hidden treasure

and I loved to be intimately known

So I created the heaven and the earth

that you may know Me

Intimately. – Hadith Qudsi

Safi separates his book of teachings into four parts: “God of Love” (“not just in God, but as God”); “Path of Radical Love” (“meditations on this overflowing”); “Lover and Beloved” (“the dance of love, being and becoming”); and “Beloved Community” (“how to achieve this in the here and now”).

“Here and now” are words that Safi repeats quite often throughout his short, passionate introduction, in case readers mistakenly assume that mystics are only concerned with the next world:

To be a mystic on the path of radical love necessitates tenderness in our intimate dealings, and a fierce commitment to social justice in the community we live in, both local and global.

Again, Safi underscores this important point by circling back to the source, the Quran: “This is God’s command: love and justice.”

Think of this book as an extended hand, holding an olive branch. Or, in Safi’s words,

I invite you to join us on this journey of love. May you find in these poems, in these luminous and fierce teachings of radical love from the heart of the Islamic tradition a mirror—one to reflect to you the beauty of your own soul.

We live in confusing times, where Islam and its practitioners need their friends. Sufism, generally speaking, remains relatively untarnished in the public imagination. But “What is Sufism to Islam?” a friend asked me the other day. The short answer is that it is its mystical branch. Books, of course, can be composed on this subject—and they have, including the valuable one currently under review. But, I think it’s safe to say that Sufism is the heart of Islam. It is both the husk and flower of the faith.

Yes, mysticism is not for everyone. One must crawl, first, before one can fly—hence the suspicion ecstatics provoke, in those who do not soar (even within the faith itself). Sufism, in turn, is the (open) secret of Islam, the poetry and beauty, when you’ve boiled everything else away (dogma, etc.). I did not think that I, a recovering existentialist, would find myself one day slipping through the back door of Islam. Yet, led by an abiding longing, I crawled like a refugee to Sufism, for succor and inspiration. To paraphrase Rumi, I let myself be silently drawn by the strange pull of what I love, and it did not lead me astray.

As Safi reminds us in his helpful anthology:

Radical love is channeled through humanity. It has to be lived and embodied, shared and refined not in the heavens but right here and now, in the messiness of earthly life.

It is difficult, I think, in times like ours, not to become radicalized . . . by Pity. May this book help heal and illuminate broken hearts and open hardened ones. I leave you with one parting quotation, which features at the opening of this love manual, by a pioneering teacher of love in the Islamic tradition, the aforementioned Sufi mystic, Ahmad Al Ghazali:

I will write you a book on Radical Love

provided you do not bifurcate it

into Divine Love

and Human Love

© Yahia Lababidi

(Images, used with permission by the artists: cloaked figure in red by Zakaria Wakrim, rose heart by Agostino Arrivabene)

Fantastic piece, Yahia.

I watch little news and live in a neighbourhood with no dominant culture or faith: people from everywhere, practicing religion and not practicing religion, speaking all sorts of languages, people of evolving gender and sexual orientations, and you know what ... we get along. We smile at each other, talk to each other, and eat each other's food. And we are not a small population but one of the most densely populated neighbourhoods in the North America. We get along and it's expected we will. Intolerance isn't tolerated well, and so I know a world that gets along is possible.

To the idea that Islam specifically needs to re-evaluate itself. No, I don't think so. The concept of Jihad has been co-opted to serve the political goals of those who want power, but beyond that there is no causation specifically between Islam and violence. Correlation does not equal causation. ANY RELIGION can be used to manipulate people to violence. Religion needs to be re-evaluated. We need to come to understand that religion practiced from a tribalistic standpoint can lead to violence. Tribalism, exacerbated by poverty and inequality, the wrestle for resources, is at the root of large-scale violence. The wrestle for resources is at the root of violence.

It is important to understand that Faith needs no religion. True faith asks nothing of you. Never. It just offers itself to those who are willing to accept its nourishment. Religion is meant to be in the service of faith and not faith in the service of religion. So be wary when a religious leader asks you to sacrifice your faith for the religion ... to defend your faith. Faith needs no defending, but a tribe that has set itself up against another tribe might.

The most attractive conceptualization of Jihad that I had ever encountered is the idea it is the act of spreading faith ... not the faith. I have gotten to the point that I know enlightenment when I see it. I have seen it times enough on Muslim faces to know that Islam can deliver it. It works and is a way to faith and the maintenance of faith. Tribalism is not, even if you call it religion. We need to remove the tribalism from religion if we want it to serve faith.

This comment went on much longer that I thought it would. Thank you for providing a venue for deeper thought:)

Namaste, dear friend:)

What a remarkable response, Pryde; your neighborhood and you are luminous examples of how we can be. Thank you, for this thoughtful and magnanimous response. You're full of heart, and I hope your short essay of a comment is widely read, to that it might help to soften hardened hearts and open closed minds. Thank you, for these noble reminders and this morning inspiration. Beam on, dear friend, and on & on <3

:)

Perfect xox

Thank you for introducing me to this book! I have been reading some of the Quran over the last several years along with the Bible and many books on spirituality. I have pre-ordered this book and will resteem your post here soon!

I'm very grateful for your generous response, Jerry @jerrybanfield. Even before I married my wife, who is a Christian, I read the Bible for inspiration, alongside Buddhist text, Tao te Ching and mystics of all faiths. I'm happy to hear that you've been reading the Quran and will help me to spread this message of peace. May the book be a ball of light in your hands. Blessings, Yahia

_/|\_The concept of them verses us is one source of hate.

I had a neighbor who went to the same elementary school as I did. Although we were friendly, playing together at times in the play ground, it is difficult to say that we were friends. For high school, I was sent to boarding school abroad. The school I found myself at had a fierce rivalry with another school in the same town that spanned at least a century. As fate would have it, my neighbor's parents sent him to that school.

The first time I met my neighbor was on a rugby field. It was the biggest game of the rugby year for both schools. So important was this game, that every year, thousands of past and current students from both schools come to watch the big game. At first, I was excited to see a face from "home", but this excitement quickly disappeared. He was one of them. He was one of the enemy.

During the school vacations, we would fly back home, often times on the same flight. I grew to dislike him, and the mere sight of him made my blood boil. As things would have it, my parents had me change schools during at the end of my second year abroad, and I never saw my neighbor again after that, because my parents moved to a different part of town.

Fast forward ten years, and I was abroad yet again and happened to bump into a familiar face in the most unexpected of places. It was him, my neighbor. This time though, I did not see him as the enemy, he was "one of us again". He was a familiar face among a sea of unfamiliarity. On that day, a new friendship began, and we have been friends since.

This experience taught me a great lesson. Anybody can become "one of them", but only when you focus on the things that make you different. Likewise, anybody can become "an us" when you focus on the things that make you alike.

If you strip away all of the superficial things, you will discover that every human being alive is the same as you. If you strip away the color of their skin, the part of the world they live in, the size of their bank balance, their current occupation, their beliefs and preferences, you will discover that what is left of them is the same as what is left of you.

So why all the hate? By focusing on the things that make others different, we will see much that we do not understand. The mind is wired in such a was so as to push us away from pain and the things that cause it. Fear is a type of pain, and we fear the things we do not understand. In the same way that you grow to hate eating certain foods, you can grow to hate that what you fear. The dissatisfaction you feel from eating that food that you hate is a form of pain, just as fear is a form of pain.

The hatred for other people that we see in the world is merely a hatred of the pain caused by the fear of what we do not understand. We can end the hatred. It is well within our ability to do so, and all we have to do is commit to understanding.

What an indirect way of addressing this post (not mentioning Islam, or Islamophobia, even once). But, I understand your larger point about fear, hate, enmity and the need to understand. Thanks, for sharing.

I realize that it was indeed very indirect, but that is because Islamophobia is only a symptom, not the disease. To cure the world of Islamophobia, racism other expressions of hatred towards other people, or groups of people, we need to cure the disease instead of treating the symptoms. What good is it to treat an ache in your body with pain killers when the cause of that pain is a cancerous growth. If you cure the cancer, the pain will go away as well, and an added benefit is that the cancer will not be able to spread.

Islamophobia is the symptom, but hate is the cancer. Let us cure society of this cancer, before it causes us more harm.

Please forgive me if this comes off as insensitive. I am not trying to diminish the effect that Islamophobia has.

Yes, I see your point :) Forgive my brief reply, but I'm spending too much time online & appreciate shorter, more to the point comments.

They started religious wars to bring us apart, named Muslims terrorist just to take away any sympathy they could get. They keep make the world look dangerous

If by "they" you mean terrorists I agree--obviously, the media and corrupt politicians do not help by fanning people's fears and promoting ignorance. May Love & Peace prevail.

_/|\_Fantastic post!

Personally I still struggle with the division that all organised religion engenders.

In my vision of a utopian world we would all simply be spiritual and understand that you and me is we.

Humanity has a long way to go.

xox

I'm glad you enjoyed it and, thank you, for sharing your thoughts.

_/|\_Properly understood, I don't think that religions divide us, as they are about love and unity. But, the fault is in us, not religions. And, I agree, that we have a long way to go...

Peace, Yahia

PS - A page from the book, above, I’m reviewing:

شكرا للمشاركة الجميلة و القيمة يحيى :)

حصلت على تصويت من

@arabsteem curation trail !

و تم اختيار مقالتك ضمن مقالات يومية مختارة للنشر في مقالنا اليومي

يمكنك الحصول على تصويت اضافي عبر ارسال مبلغ اقله

0.05

ستيم او اسبيدي الى حساب التصويت الالي

@arabpromo

مع رابط المقال في حقل المذكرة (memo)

مما يتيح لك الحصول على تصويت مربح بحوالي 2.5 اضعاف :)

Thank you, for your support. I think this is an important book for the Arab/Muslim community, in changing how we are perceived and, also, how we might perceive ourselves. Ramadan Kareem to all, and heaven help us to be the change we wish to see.

_/|\_Wow amazing