A few weeks ago, I turned up in a village called Arin in the Sacred Valley near Cusco, searching for a mysterious wizard by the name of Taki. At least, I like to think of him as a wizard, because mushrooms are magical.

Taki grows mushrooms. After forming an interest in mushroom cultivation while living in Mexico, Taki brought his knowledge to the Sacred Valley, Peru where he’s been the local supplier of mushrooms for about eight years. Though born in the United States, Taki’s mother is Peruvian. Perhaps that’s where his compassion for the local community comes from. “At first, we were selling to businesses and friends,” Taki explains. “But the money isn’t where my heart is, so I toned down production to allow more space for me to enjoy life. I’ve also refocused the mission; now our aim is to run workshops on how anyone can grow their own mushrooms. We’ve given workshops to local Quechua people and sell growers’ starter kits at a fair price so that any family can start supplementing their diet or even their income straight away.”

Following Taki through the farm, we explore different stages of the mushroom cultivation process.

[As of March 21, there are restrictions on travel and mandatory social distancing is in place. This article was written with the reader’s health and safety in mind, you’ll find some of the studies cited here interesting; fungi may play a helpful role in preventing viral infections and strengthening the gut biome.]

Mushroom Food

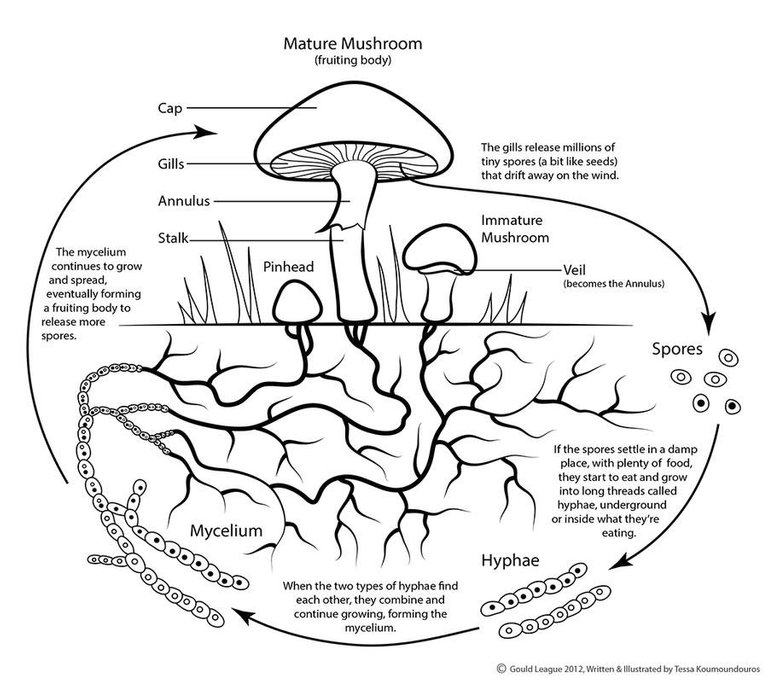

“Today we are mixing these bags of oyster mushroom mycelium with pasteurized straw,” Taki explains to us. Next to me are three volunteers who found Taki through Workaway. We learn that the straw serves as a substrate for the mycelium to feast upon until it reaches the fruiting stage (the point at which mushroom fruiting bodies begin to form). “First we disinfect all surfaces and tools,” Taki explains. “Including our hands all the way up to the elbows, and we wear sterilized gloves.”

“This is straightforward open-air spawning,” Taki’s brother says as we unload three steaming sacks of straw onto a table. We spread the heap until it’s cool enough to mix in the mycelium (cultivators call this ingredient “spawn”, or the living mass of fungi that will later produce mushrooms when conditions are met). It’s important for the temperature to be low enough that it doesn’t cook the fungi.

It takes a couple of hours to cool down the straw and then mix the spawn evenly throughout the substrate, and finally pack it all into black trash bags. The trick is to keep it just loose enough for the mycelium to spread easily, without leaving any pockets of air and moisture between the substrate and the bag.

Taki supplements his oyster substrate with 5–8% of wheat bran to get more mushrooms. “Adding the bran drastically increases the yield, but if you add too much then it’ll get a bacterial infection. Too much of a good thing can become toxic.”

Taki leads me over to a wide barrel that’s full of sacks stuffed with straw. He uses a compost thermometer to check the core, “But I usually just put a finger on it to test the temperature for two seconds,” Taki says. “If it burns me in under two seconds then it’s ready.” Checking the thermometer, he continues, “The main issue is that people aren’t sterilizing long enough. The middle of the pot won’t get to the optimal temperature for pasteurization. It needs to remain between 160 and 180 degrees Fahrenheit for more than an hour. Anything more than that may kill the beneficial bacteria that defends the fungi.”

He drains the barrel while speaking, “If you don’t drain the chamber early, then the substrate will grow mold or parasites. The spawn becomes anaerobic, or an oxygen-free environment where mold thrives. That’s why we check for a sour scent every morning. The substrate should instead have a pleasant smell.” Once our work outside is complete, I follow everyone into the mushroom incubator.

Inside a Mushroom Incubator

“It takes a long time to fully colonize from the top,” Taki says. “But doing it this way is straightforward. All you need to do is let it sit in a dark, damp place. We do all that in the incubation room. Once every day we go in here and spray a water hose onto the walls (never directly onto the mushrooms). You can see the spores floating in the air, it’s pretty neat.”

Taki practices a rural method of mushroom farming commonly used in Asia by small farmers. Colonization happens a bit slower, “One and a half months for oysters,” Taki says. “It’s about two months for reishi, and shiitake takes roughly five months on sawdust bags.”

After a few weeks, the substrate will be fully colonized and prepared to enter a fruiting stage. At that point, Taki cuts slits into the sides of the bags. The fungus does the rest, and in only a few days he carefully harvests the fruit (mushroom).

Taki shows me the bags of shiitake. The mycelium is dark brown as if it created its own bark. The reishi resembles an alien in every way. “For shiitake and reishi, we use a basic cotton plug method. Pasteurize the bags with the plug left inside, and then to inoculate you simply pull the cotton out, drop some spawn from a petri dish down the hole, then return the cotton plug.”

“How often do you get contamination?” I ask.

“We get a rotten egg or two with every batch, but nothing too concerning. When a bag is contaminated, it becomes visible all over the bag. If one of these gets sick,” He pats a trash bag with a tower of oysters flowing out of it, “we put it outside to fruit apart from all the other bags.”

Even after a bag has a hole in it and bugs spread inside, the fungi can still fruit in the outdoors. A lot of spent material from the farm becomes mulch for the gardens, where often you’ll spot a fat mushroom emerging right next to a head of lettuce.

Taki points to where we’ll place today’s freshly spawned-to-substrate oyster bags and says, “There’s a five-day difference in colonization time during the winter. The Andean winter is May through September, so it’s summer right now. In February, oysters and reishi are so aggressive that they often fruit through the bag’s filter patch!”

Pressure cooking in the wizard’s hut

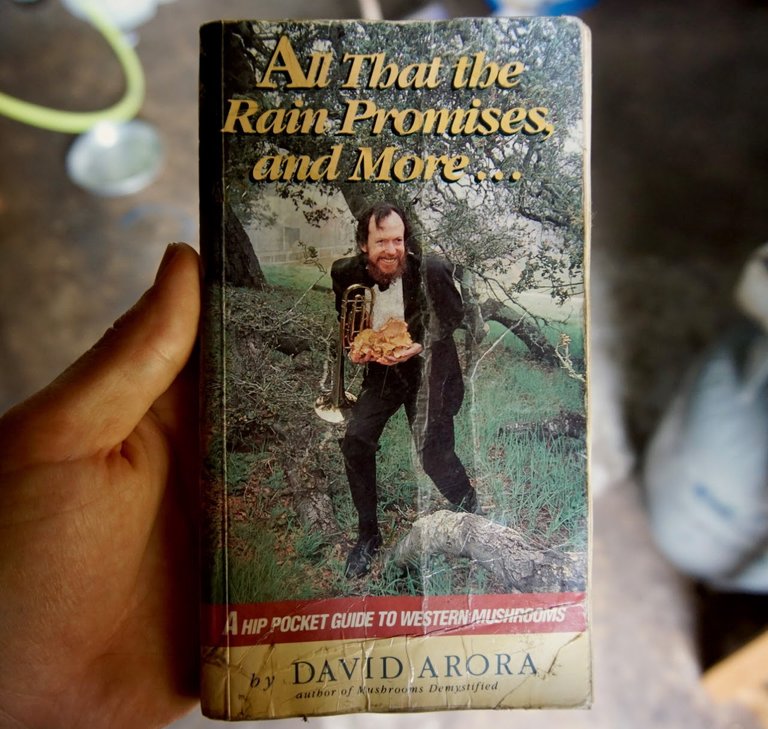

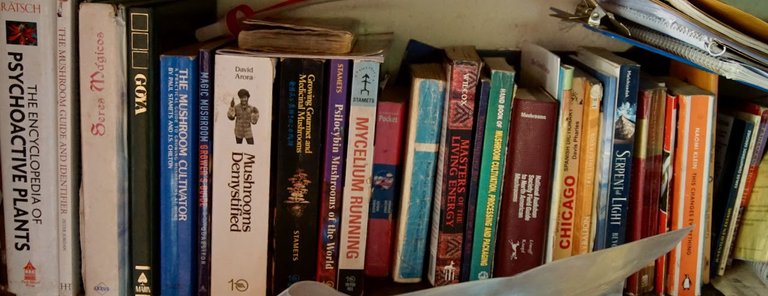

I walk into Taki’s kitchen-library, the shelves are straight out of Hogwarts with bottles and vials of magical concoctions, shells, bones, crystals, and books containing a century of knowledge about plants and fungi. This is where Taki handles most of the sterilization process at the farm. I’m surprised by how straightforward this stage actually is, but honestly quite distracted by a decaying textbook from the wizard’s shelf titled The Encyclopedia Of Psychoactive Plants.

The first step of sterilization is filling quart jars with wheat grain, screwing on the lids, and loading the jars into a pressure cooker. Autoclaves are great for bulk sterilization, but they’re also expensive. Taki was fortunate enough to buy several All-American pressure cookers at a town auction. “With jars, you only need an hour and a half at fifteen PSI for proper sterilization,” Taki explains. “But if the cookers are packed with filter-patch bags then you’ll need six hours due to the lack of air space.”

Wide-mouthed jars are easiest to work with when it comes time to remove the fully colonized spawn from the jars, but filter-patch bags are a perfect alternative. Sifting through the bookshelf, I ask Taki about some of the health benefits of his mushrooms.

Medicinal mushrooms and the immune system

Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) is one of Taki’s best sellers. Well known for their umami flavor, eating shiitake mushrooms regularly may help boost your immune system and strengthen the gut. At the time of this writing, Coronavirus has spooked nearly everyone in the world, so eating something that fights against viruses or a nasty bug that may land me in the hospital is easily worth it.

The polysaccharides found in shiitake and other edible mushrooms may have an anti-cancer effect. In fact, all of the mushrooms Taki grows have a high level of polysaccharides and thus offer protection from viral infections, while shiitake stands out for its tumor-inhibiting properties.

Beyond polysaccharides, β-glucans are some of the most impactful compounds in mushrooms, and shiitake is high in them. β-glucans have shown positive and preventative effects on cancer, hypertension, and high cholesterol levels. You can tell by now that I obsessively researched mushrooms for at least a week while writing this.

Because the highest concentration of β-glucans is in the fruiting bodies of the fungus, it’s important that supplements are made with real fruiting bodies and not just hunks of mycelium and grain that are nearly void of magic β-glucans. Unfortunately, many companies are selling supplements containing myceliated grain, but Taki makes his supplements with fruiting bodies. I think that adds a lot of value to the product.

Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceum) is another contender for fighting tumors and inflammation while boosting the immune system, and it’s as healthy as it is delicious. Cooked up with some salt and butter, this stuff tastes like literal crab meat. All of the farm’s supply was still growing in the lab, so I wasn’t able to see any of the fruiting bodies during this visit. Lion’s mane also regenerates nerve cells, meaning it may prevent or regulate neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s).

Cordyceps (Cordyceps militaris) contain Cordycepin, which has a very potent anti-cancer, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Not only that, but they also improve athletic performance and benefit the immune system. Taki regularly sends samples of his cordyceps to a friend in Hong Kong to test for cordycepin levels, ensuring that his product is high quality. I didn’t get to see any of these mushrooms, as they were currently growing in the lab. What I did get to see was a load of reishi and oysters mushrooms.

Eating oyster (Pleurotus ostreatus) mushrooms lowers cholesterol, plus it’s high in antioxidants, and like all edible mushrooms grown in optimal conditions, they’re a good source of vitamin D. They’re affordable, easy to grow, and probably offer protection against the flu. They also go well with butter and salt.

Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) may be the strangest-looking mushroom at Taki’s farm, but it’s also one of the most medicinally powerful. Renowned for thousands of years in Asia as the “mushroom of immortality”, I was surprised to not find many publications on their medicinal benefits, but this study shows reishi to be effective against cancer (culinary note: reishi is purely medicinal, it tastes bitter and in general quite bad, so I’d opt for making tea rather than a stir fry).

Business & how to make your own

“Most of the supply goes to Cusco,” Taki explains. He’s cooking up some sweet potato stew while we chat about business. “The rest we sell here in the Valley. Ten to twenty kilos per week, directly to restaurants and a few grocery stores. I’d say we max out at eighty kilos of mushrooms per month. That number used to be about 100 to 150. But like I said before, it’s hard work and honestly not worth it for me at the moment. Maybe in the future, when we build up the property. In the long run, I‘ll sell more medicinal supplements than fresh mushrooms.”

When Taki moved to the Sacred Valley eight years ago, gourmet and medicinal mushrooms were a new thing even in Cusco. There weren’t any other growers out there, but now there’s more competition and it’s not as lucrative to sell large quantities of fresh mushrooms anymore. However, most varieties of mushrooms are still unfamiliar to locals. “People are unsure of what they’re looking at when they see reishi and even oysters in the market. A lot of the farmers know what they are by now, and the demographic of foreigners who settle in the Valley are a bit more inclined to know about medicinal mushrooms. But all that said, there’s definitely still room in the market for more growers.”

Taki is more interested in teaching people how to become growers than producing mushrooms for the market. “I’m out of the competition game,” he tells me. “I think that if I make even a tiny mark on the industry and local economy in a positive way, then that’s a good thing. Many families here live on very little and people farther afield have it even tougher in the winter. But any family can grow mushrooms the way that I do, and it wouldn’t take much of an investment to buy some bags that are ready to fruit, just to see what it’s like to grow your own.”

Foraging in the Andes

“Have you tried foraging for mushrooms in the area?” I ask Taki. He says that he goes into the valleys nearby sometimes to hunt for slippery jacks (Suillus luteus) and during morel season he treks into a canyon not far away from Arin, but wild edible mushrooms aren’t common in the region.

“There’s a famous mushroom that only grows here in this part of the Andes,” Taki says. “They’re sold in the San Pedro Market in Cusco, dozens of ladies with baskets of little brown mushrooms. People have been trying to grow them but no one can figure out how to make the mycelium fruit.”

“They must be too sensitive to grow outside of their natural environment,” I say. Taki tells me there’s a similar issue with maitake (Grifola frondosa), another delicious and medicinally potent fungus. So far he hasn’t grown them successfully in eight years due to the climate in the Sacred Valley. It wouldn’t be cost-effective to maintain the temperature for maitake to thrive. However, he has a new strain that’s colonizing well, so perhaps we’ll begin to see fresh maitake for the first time in the Sacred Valley within a year.

Peeking inside the mushroom lab

“You’d have to take a shower before stepping in here, but you can watch from the window.” Having lost a lot of my own mushroom projects to contamination, I respected a distance from the lab. It doesn’t take much at the inoculation phase of fungi cultivation to ruin a project. “We let all the spawn bags run in here, after inoculating them in front of the flow hood. If we didn’t have this machine, our success rate would be pretty low even with oysters, hardy as they may be.”

Inside the lab are a workbench in front of a flow hood and several racks of filter-patch bags. Inside the bags, several species of fungi are growing at different stages. “Not everyone can afford a lab setup like this,” I say through the doorway, “Many can’t afford a high-quality flow hood. What can you recommend to people who are just getting started?”

“Home growers are using plastic containers to build still airboxes. The idea is to limit the movement of particles in the air, so the box is made with just enough room to put your hands inside. The typical setup is to stack an alcohol burner on one side, which creates a kind of sterile vacuum effect in the chamber, and on the other side, place sterilized objects like colonized Petri dishes and jars or new dishes you’re going to inoculate. The trick is to limit movement across objects. Be fast, methodical, and use a whole lot of 70% isopropyl alcohol.”

As an alternative to doing all the lab work yourself, Taki supplies pre-colonized bags of spawn as well as pre-mixed bags of spawn and substrate ready to grow mushrooms within a few weeks. In the long run, I think that what’s more affordable for the grower is according to their own situation. Most people have enough space, but finding sterile lab conditions to create your own spawn is the most difficult and arguably most important step.

If you can’t make it out to Taki’s farm or you’re not based out of the Sacred Valley, I highly recommend checking out this walkthrough on growing your own mushrooms from step zero to harvest, all from home.

Mushrooms are groovy, what else do I need to know?

They’re delicious, prevent disease and support our overall health, and can even supplement our diet and income. But not everyone knows the benefits of fungi or how to grow them at home. That’s the gap that Taki’s workshop fills.

Taki currently grows oysters, reishi, lion’s mane, and cordyceps at his farm in Arin. He continues to supply fresh mushrooms to local businesses and spends time at the nearby green market on Mondays. His passion is in teaching other people about fungi and how to grow their own. In the near future, Taki plans to focus more on medicinal mushroom production.

Click here to find out more about Taki’s Workaway project, where you’ll learn all you need to know about mushroom cultivation whether you’re a hobbyist or thinking about starting a farm of your own.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://medium.com/swlh/where-mushrooms-grow-in-peru-and-their-benefits-757c626bfeff