In the afternoon of May 21, 1946, less than a year after the bombing of Hiroshima, in the heart of the secret laboratory built for the purpose of building nuclear weapons, Lou Slotin unleashed hell.

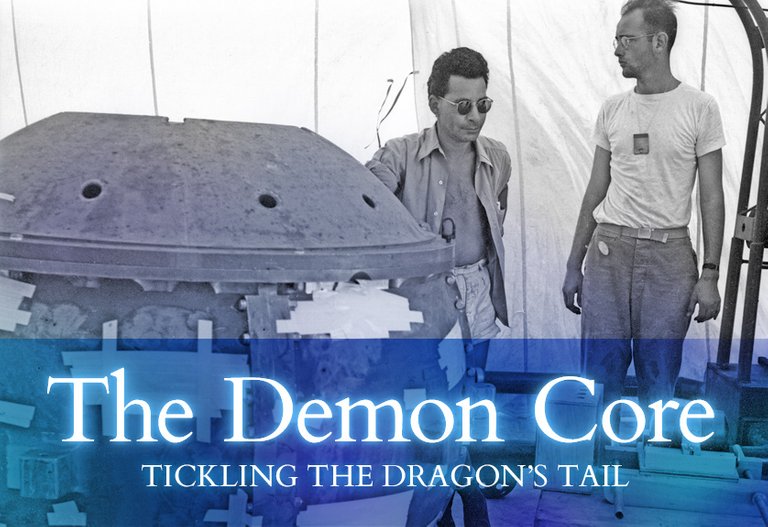

The nuclear scientist, was working in one of the many makeshift laboratories at Los Alamos, a wooden structure with no radiation protection. Surrounded by observers, he was playing with what would later be known as the Demon Core: a sphere of Plutonium, the core of a nuclear weapon, made in anticipation of future bombings against the Empire of Japan. But the Empire surrendered just four days before the bomb was to be dropped. It was taken apart, and the Plutonium core stored at Los Alamos for research.

Slotin's job was described by Richard Feynman as “tickling the dragon's tail”: testing how far the core could be prodded with radiation before it underwent a chain reaction.

The experiment was simple: a sphere of Plutonium not four inches wide sat in a hemisphere of Beryllium, a polished mirror of neutrons. The other hemisphere was to be lowered onto the Plutonium, covering more and more of its surface area as more neutrons became trapped inside and the radiation ticked upwards. Nowadays an experiment like this would be performed by robot, with the experimenters working far from the laboratory. But Slotin was doing it by hand – holding the Beryllium hemisphere by the tip of a screwdriver – shielded only by a wall of radiation-shielding bricks.

In a moment of carelessness, the screwdriver slipped just a fraction of an inch, and the upper hemisphere fell, encasing the Plutonium entirely. The room was flooded in the electric blue of Cherenkov radiation: the color of air burning with electrons moving faster than the local speed of light. The chain reaction was over ever before Slotin reached in and, with his bare hands, flipped off the Beryllium mirror from the red-hot Plutonium assembly.

Enrico Fermi, the physicist who would become one of the chief architects of the Hydrogen bomb, saw it coming. He warned Slotin and his entourage that if they kept doing the experiment in those cavalier conditions, they would be “dead within a year”.

In the end Fermi's prediction came to pass; Slotin took nine days to die, his immune system decimated, his skin burnt by radiation, his body overflowing with rapid-growth cancers. Alvin Graves, who was standing a few feet from him, died thirty years later from a heart attack aggravated by radiation. Two more died decades later of diseases that are only now known to be linked to radiation.

The experiment was dramatized in Fat Man and Little Boy, a movie of the making of the bomb:

After the accident, Slotin – played by John Cusack – tosses pieces of chalk to others in the room, for each to mark their place for the calculations on how much radiation each had received. Left on the floor of the room was every metal object they carried, as metal becomes radioactive when irradiated.

Bizarrely, this was not the first time that same core – that same sphere of five-cent Plutonium – had killed someone. In the first incident, nuclear physicist Harry Daghlian was setting up the experiment, building the small wall of tungsten carbide bricks – shown in the clip above – to shield himself from the dangerous radiation. His hand slipped, a brick hit the core, and the reflected neutrons were enough to trigger a brief chain reaction – just long enough to sentence him to death, and to poison a security guard sitting a few metres away. Daghlian died just 25 days after the incident, the guard, more than thirty years later of a rare form of radiation-linked leukemia.

The deadly core was scheduled to be reused for Operation Crossroads, the famous tests of underwater nuclear explosions. But this experiment, like this original mission of the core, was canceled: the first two tests of Crossroads revealed unexpectedly high levels of radioactivity, and the next were canceled.

In the summer of 1946, the core was melted down and recycled into a new bomb.

Blue here, hope you liked this post, and stay tuned for future posts on the intersection of science and history.

Great article on a very interesting subject.

You've got a lot of writing skill.

Very interesting!

I really enjoyed reading this post and learned a lot. Thank you.

No, thank you!

~ Blue

The safety measures were not very demanding :P

Congratulations @tombritton! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honnor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPBy upvoting this notification, you can help all Steemit users. Learn how here!

Neat.