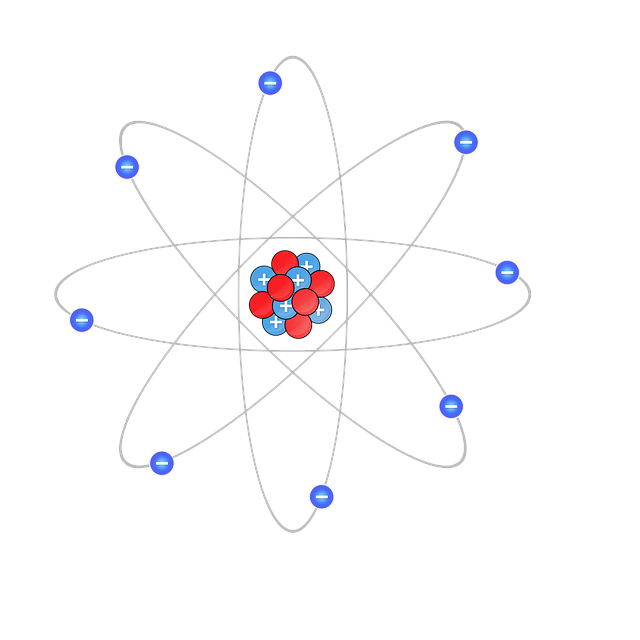

The Atomic Model allows us to describe and graphically represent the structure of atoms. But it is only a model – “the map is not the territory!”

Most of what we know about atoms has been discovered in the last 150 years. But how did we get to our present understanding? Who were the key people who made the key discoveries? And what did people believe before these models were accepted?

This post aims to answer all these questions. So without further ado, let’s travel back in time to…

The Philosophers of Ancient Greece

In Ancient Greece, philosophers began thinking about the nature of reality. They asked questions like ‘is water a continuous thing, or is it made of smaller parts?’; ‘if air is empty space, how is it I can feel the wind on my face?’; ‘if I crush stones I get dust. What will I get if I crush the dust? Will I get something that cannot be crushed further?’

The philosopher Democritus thought that everything was made of particles, which he called ‘atoms’, meaning indivisible. He came up with all sorts of theories about what they might be like, what shape they might be, what they might taste like. But advanced experimental methods didn’t exist yet.

Aristotle on the other hand was convinced that everything was made up of the 'elements' of water, earth, air, and fire, in different proportions. He assumed that you could keep on crushing stone forever into smaller and smaller pieces, but that those pieces would always be stone no matter how small they got.

Alchemy in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, alchemists did lots of experiments, motivated by a desire to turn base metals like lead into precious metals like gold, or to find an elixir of life.

They didn’t succeed in synthesising gold or finding an elixir, but they did perfect certain scientific techniques, like crystallisation and distillation, which are still important today.

Unfortunately, some alchemists were motivated by greed, and conned people out of cash by making promises of giving them gold. So the reputation of alchemists was tarnished.

Robert Boyle, Joseph Louis Proust, and John Dalton

In 1661, Robert Boyle was experimenting with compressing gases. He made a number of observations which led him to believe that gases were made of particles with lots of space in between. He also defined elements as substances which cannot be broken down into simpler substances. The idea of atoms was back on the table.

Joseph Louis Proust was experimenting in the late 1700s, and noticed that elements always reacted in fixed ratios, which suggested that elements were indeed made of discrete particles.

In the early 1800s, John Dalton, an English scientist, was performing experiments to look at how substances changed state from liquid to gas and back again, observing that liquids turned to gases at different temperatures when the pressure was higher or lower. In fact, even though different liquids would turn to gas at different temperatures, he noted that any known change in temperature or pressure would give predictable results for all of the liquids he experimented with. So, there must be fixed laws governing thermal expansion.

He published his results, and this time, the idea of atoms was accepted quickly by scientists all around the world.

Brownian Motion

The trouble was, atoms were too small to be seen. They are smaller than the wavelength of light, so they couldn’t be seen even with the best optical microscopes.

However, in 1827 the Scottish botanist Robert Brown was looking at pollen grains in water. He saw that they were constantly in motion. He thought pollen might be moving because it was alive. So he tried it with dust. And dust stayed in motion too! He came up with the idea that the particles moved because they were being bumped around by the water particles. This motion became known as Brownian Motion.

That everything was made of tiny particles was no longer a theory. Though these particles were not visible, their effects on other larger particles could be seen.

In 1955, Erwin Muller invented a field-ion microscope, which could create an image magnified millions of times. When scientists looked at the point of a needle through it, they could see that the needle was made up of tiny dots. Finally we could ‘see’ atoms.

Atomic model image

Aristotle image

Alchemy image

Brownian motion gif

Hello, I am the admin of the facebook group ''Steemit for Resteem'', please read our rules to post in the group : Steemit for Resteem Rules↕.