Certain bacterial species naturally reduce (or donate electrons to) metals in their immediate environment. If the bacteria are in the presence of dissolved uranium, such as in groundwater, this reduction changes the reactivity and reduces the solubility of the contaminant. This reduction can halt the further spread of contamination.

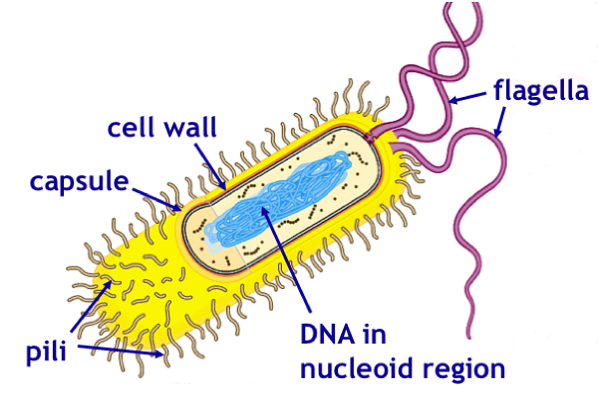

It was thought that filaments, called pili, facilitated this reductive microbial process, but these tiny hair-like structures only form under certain conditions. Researchers recently were able to induce Geobacter to form pili by subjecting them to stressful conditions, such as reduced temperatures, and were thereby able to study the structures in depth. They found that the pili allowed the bacteria to reduce a much larger amount of uranium, due to greater surface area available for electron transfer as well as protecting the bacteria from radioactive harm. Bacteria without pili must reduce uranium inside the cellular envelope, exposing the cell to damage and inhibiting its reductive activities. The pili however, keep the uranium at a safer distance from the cell.

An article published in Nature Nanotechnology makes the claim that these pili are a type of electrically-conducting nanowire. The pili transfer free electrons produced from bacterial metabolic processes to acceptor ions outside of the cell, such as iron or uranium. This step is essential to bacterial survival, but can also be utilized for a variety of bioremediation applications, including clean-up efforts at cold war-era uranium processing facilities. In theory, this process could be applied to radioactive isotopes of other elements such as cobalt and plutonium. Other pili-forming bacteria, including thermophilic methanogens and photosynthetic cyanobacteria may also function in this manner. Researchers are now looking at ways to mimic these same reduction processes with non-living nanowires based on the bacterial pili. Such devices may allow for more fine-tuned control and selectivity by adding different chemical functional groups to the nanowires. The scientists hope the devices would be able to function in nuclear reactors where bacteria couldn’t survive, providing a low cost, environmentally friendly solution to an ever-present danger.

Neat. Here's a link to the Nature article I found.

That's pretty interesting. I dont think that I'm smart enough to fully understand it but the technology is pretty incredible

Posted using Partiko Android

Wow, most of it was over my head, but it was a very interesting read. It is awesome how they are constantly applying things we already know about to new problems in unique and clever ways. Thanks for sharing!

Interesting. The fact that the bacteria reduce the solubility of uranium could definitely be useful in the sequestration of the radioactive element. It definitely could be applied to other radioactive elements, maybe even just by exposing the bacteria to them over time. There's a process called directed evolution, where an organism is exposed to a mutagen and the desired substrate. Over time the organism mutates at random, and eventually a colony is isolated that can act on the new substance. In this case it could polonium, plutonium etc.

Yep, ok. Very interesting and sounds like there may be a commercial use. But it is a little over my head @pinkspectre.