For a few hours in May 2016, for the first time in more than a century, Britain was burning zero coal to generate electricity. None at all. All the coal-fired power plants were turned off. And this here is one of the reasons why. The Griffin Wind Farm in Scotland. 68 turbines, more than 150 megawatts of capacity.

And the turbines rotate and trim the blades to track the wind in real time. At full output, this can power entire cities just from the wind. But as the world moves to renewable energy, we’ve got a little bit of a problem. Because coal, oil, gas, and nuclear stations are basically just giant boilers. They take water, they heat it up, that turns to steam, the steam gets forced through a massive turbine which rotates and generates power. When I say turbine, I don’t mean like the blades in Griffin Wind Farm , I mean hundreds of tonnes of steel rotating thousands of times a minute. And all those turbines, all around the grid, rotate in sync with each other. After gearing, they all move at 50 cycles a second. 60 in America. All perfectly in time: one slows down, they all slow down. One speeds up, they all speed up.

And that is what stops your lights from constantly flickering. Because electricity supply has to always match demand, pretty much exactly. There isn't a battery in the world big enough to store power on a national scale. So if a power station suddenly falls off the grid for some reason, then where’s that supply going to come from? And the answer is the kinetic energy that’s already in the turbines, in that spinning thousands of tonnes of steel around the country. Homes and factories will literally suck the kinetic energy out of that turbine to cover the gap, starting to slow it down. But that won’t cause a problem for 60 seconds or so, and in that time the National Grid Control Centre will, I don’t know, throw another nuclear rod on the barbie and up the power output from other stations. They'll cover the demand.

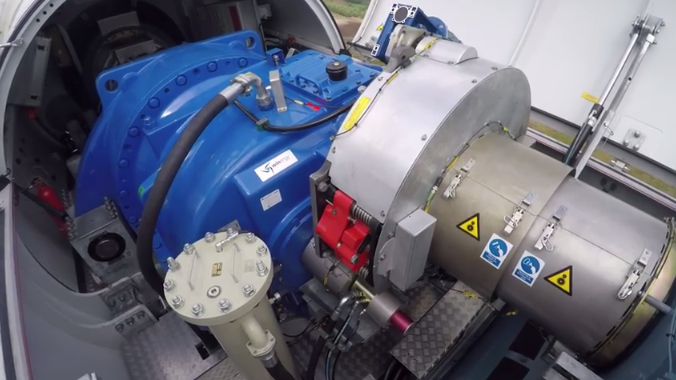

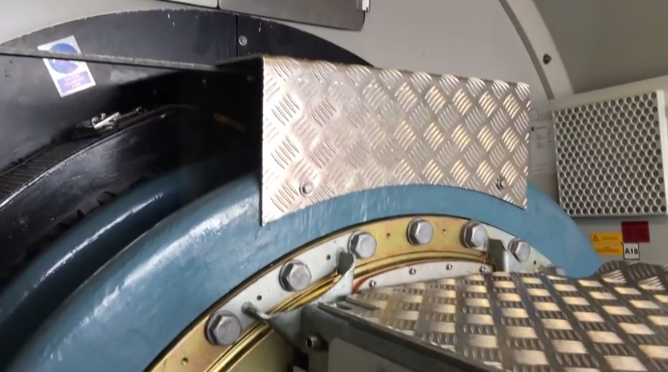

But, well, that relies on having enough rotational mass, enough system inertia, as it’s called. And here, in this turbine? Well, you can see.

There’s no hundreds of tonnes of spinning steel, just some blades, a bit of metal, and some circuitry that feeds the power into the grid at the right frequency.

If the whole grid were running on just wind and solar, there's no rotational mass. There's no grid stability. The minute that supply and demand mismatch, breakers would trip, and the whole thing would fall apart. Now there are some possible solutions to this. Pumped hydro storage has been around for a while, which is where you have two lakes at different heights. When you’ve got too much power, you pump water up, and when you’ve got not enough, you drop it back down again through generators. But that takes seconds or minutes to kick in.

There’s also some experiments going on with things like molten glass storage, compressed air storage, and flywheels, but they’re all experimental at the minute and not particularly efficient. The actual solution may come from somewhere a little unexpected. Because yes, wind is replacing coal and oil, but it’s also replacing petrol, the gasoline that you put in your car. And as more and more and electric cars get connected to the grid, well, you’ve got a load of quite large batteries with computers.

Your car could sell power back to the grid in real-time, second by second, as it’s needed. Combine that with smart appliances and meters that can watch the grid and work out when would be the best time to turn on your air-conditioning and fridge is, and you have a grid that does a lot of the balancing itself. Yes, we will probably always need a turbine somewhere, some big spinning mass of steel to cover the little glitches second to second, but the solution to balancing a power grid is not what we thought it was 20 years ago.

It’s not big, monolithic batteries. It’s millions of small ones up and down the country.