Other posts of the series here:

1 - Evidence for a Limit to Human Lifespan

2 - The Importance of Stupidity in Scientific Research

Hey there

Today I bring you a new paper that is The Dieter's Paradox.

Despite the vast efforts to promote the consumption of healthy foods and the public's growing concern with weight management, the proportion of overweight individuals continues to increase. Healthier meals are perceived to be less likely to promote weight gain, so people erroneously assume that adding a healthy item to a meal decreases its potential to promote weight gain.

This argument can be illustrated by the finding that people tend to believe that adding a healthy option to an unhealthy one decreases, rather than increases, the calorie content of the combined meal. This means that people tend to believe that an healthy option (like a side salad) have negative calories. The autor refers to this misperception as the negative calorie illusion.

The increased awareness of one's weight has been identified as a key aspect of behavioral modification aimed at reducing overconsumption. So we can expect that people concerned with managing their weight will be able to more accurately determine a meal's calorie content? And also less likely to be susceptible to estimation biases, such as the negative calorie illusion?

Actually no.

As this research will demonstrate, this is not the case. The belief that adding a healthy item reduces a meal's potential to promote weight gain is not attenuated among individuals concerned with managing their weight. In fact, just the opposite occurs: It is much stronger for those individuals. Thus, weight-conscious individuals, including those on a diet, are more likely to believe in a paradox: that a meal's tendency to lead to weight gain can be decreased by simply adding a healthy item. The autor refers to this phenomenon as the “dieter's paradox.”

Building on prior findings, this research argues that the negative calorie illusion stems from people's tendency to categorize foods as healthy (“virtues”) and unhealthy (“vices”) according to a good/bad dichotomy.

When presented with a meal that combines both a virtue and a vice, people form an overall impression of this meal's healthiness in a way that the vice/virtue combination is perceived to be healthier than the vice alone. Because people rely on their evaluations of a meal's healthiness to determine its calorie content, they consequently conclude that a meal combining a healthy and an unhealthy item has fewer calories than the unhealthy item alone.

This line of reasoning suggests that the negative calorie illusion is more likely to occur among individuals who have a stronger tendency to categorize foods into virtues and vices.

In the experiment, respondents were shown four meals and asked to estimate each meal's calorie content. The data show that respondents believed the unhealthy meal alone to average 691 calories. Logically, one would expect that adding another item to this meal would increase its calorie content.

The data show, however, that adding a healthy item resulted in a significant decrease, rather than an increase, in the meal's perceived calorie content to 648 calories. This bias was observed in all four meals tested, indicating the prevalence of the belief that one can consume fewer calories by simply adding a healthy item to a meal.

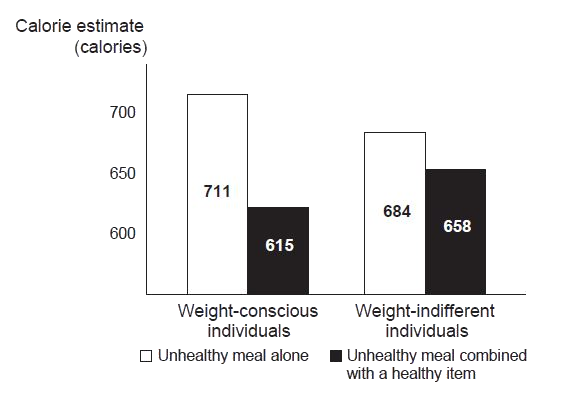

The data also shows that respondents most concerned with managing their weight perceived unhealthy meals containing a healthy option to have significantly fewer calories than those who indicated lower levels of concern with their weight.

Figure bars indicate the average estimates of a meal's calorie content:

The difference between the evaluations of the unhealthy meal alone (white bars) and the unhealthy meal combined with a healthy item (black bars) is the negative calorie illusion.

Adding a healthy option decreased the perceived calorie content of the combined meal by an average of 96 calories for weight-conscious individuals but only 26 calories for those less concerned with their weight. The dieter's paradox was observed in all four meals tested, lending support to the proposition that weight-conscious individuals are more likely to believe that by simply adding a healthy option one can lower a meal's calorie content.

One might argue that the negative calorie illusion stemmed from participants' belief that the unhealthy item was perceived to be somewhat healthier (and hence more likely to have fewer calories) just because it was next to a very healthy item. The data show, however, that merely placing a healthy item next to an unhealthy one did not decrease its calorie content. This suggests that the dieter's paradox cannot simply be attributed to a change in people's perception of the healthiness of the individual components of a meal (e.g., due to a “spillover” effect) and is rather a function of people's holistic evaluation of combinations of healthy and unhealthy items.

The finding that individuals' motivation can lead to decision biases raises the question of identifying the psychological underpinnings of this process. In this context, one could argue that the dieter's paradox can be attributed to the fact that individuals are rationalizing their decisions in such a way that those most concerned with managing their weight are also most motivated to think that the combination of a vice and a virtue has fewer calories.

An important aspect of public policy, therefore, should involve educating consumers about the differences between a meal's healthiness and its calorie count—in particular that although adding a healthy item can make a meal healthier, it cannot lower its calories.

This research shows that focusing only on virtues can implicitly promote the erroneous belief that the healthy aspects of the meal can compensate for its unhealthy aspects, and that an unhealthy meal can be made healthier and less likely to promote weight gain by simply adding a healthy item or ingredient.

Focusing the public's attention on the quantity of the consumed meal can help eliminate the negative calorie illusion and, in turn, eliminate the dieter's paradox.

Higher levels of motivation lacking the corresponding knowledge can lead to counterproductive outcomes. In this context, public policy should focus not only on encouraging consumers to manage their weight but also on educating them about important aspects of healthy eating, such as the difference between a meal's healthiness and its propensity to promote weight gain, as well as the importance of monitoring the overall quantity consumed.

References:

Chernev, A., The Dieter's Paradox, Journal of Consumer Psychology (2010), doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2010.08.002

Keep in touch

Legman

Not indicating that the content you copy/paste is not your original work could be seen as plagiarism.

Some tips to share content and add value:

Repeated plagiarized posts are considered spam. Spam is discouraged by the community, and may result in action from the cheetah bot.

Creative Commons: If you are posting content under a Creative Commons license, please attribute and link according to the specific license. If you are posting content under CC0 or Public Domain please consider noting that at the end of your post.

If you are actually the original author, please do reply to let us know!

Thank You!

More Info: Abuse Guide - 2017.

Don't just copy paste directly from source material.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057740810000987