About 70% of the Earth's microbes live in its depths, in rocks that were considered sterile but where bacteria and unicellular organisms abound, according to several scientists who, for the first time, have estimated the magnitude of this "intraterrestrial" life.

Hundreds of international researchers from the Deep Carbon Observatory program published Monday at the US Geophysics Summit in Washington, the sum of their work, according to which the deep life represents a mass of 15,000 to 23,000 million tons of carbon, 245 to 385 more than the 7,000 million humans.

That had never been quantified, since before the scientific community did not have specific observations.

Hundreds of international researchers from the Deep Carbon Observatory program published Monday at the US Geophysics Summit in Washington, the sum of their work, according to which the deep life represents a mass of 15,000 to 23,000 million tons of carbon, 245 to 385 more than the 7,000 million humans.

That had never been quantified, since before the scientific community did not have specific observations.

Participants in this international collaboration, which took place over ten years, carried out hundreds of drilling under continents and oceans.

A Japanese ship drilled 2.5 km under the oceanic plate, capturing microbes that had never been observed and that lived in a layer of sediments of 20 million years.

"Microbes live everywhere in the sediments," Fumio Inagaki, of the Japanese Agency for Marine and Earth Sciences, told AFP. "They are there and they wait ... we still do not understand their mechanisms to survive in the long term," he said.

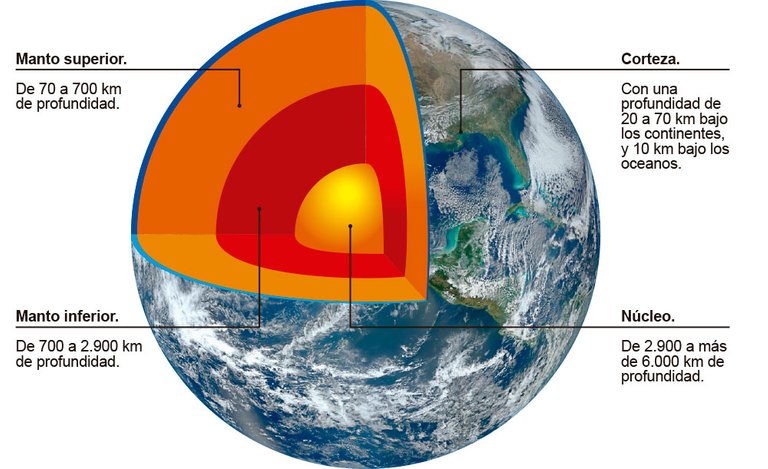

These organisms live several kilometers below the surface, in the earth's crust, and apparently have evolved independently of surface life.

"These are new branches of the tree of life that have existed on Earth for billions of years, but we have never taken them into account," Karen Lloyd of the University of Tennessee told AFP.

These microbes are mainly bacteria and unicellular microorganisms, and some of them are zombies: they use all their energy to survive, without any activity, in isolated areas of the surface since time immemorial, for tens of millions of years or more.

Subjected to extraordinary pressure and deprived of nutrients, some do not reproduce and do not have any metabolic activity to recover.

Other bacteria, on the other hand, have a certain activity and fascinate biologists because they work in a system that has nothing to do with the earth's surface, where the entire food chain depends on photosynthesis, which makes plants grow and It allows to nourish a set of organisms.

"Its source of energy is not the sun and photosynthesis," Bénédicte Menez, head of the geomicrobiology team at the Institute of Physics of the Globe in Paris, told AFP. "Here what makes communities work is chemosynthesis, they get their energy from the rocks when they are disturbed."

- What are they for? -

The record of the observations is held by a single-celled organism named Geogemma barossii that has been found in hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the oceans: it lives, grows and reproduces at 121 ° C.

Deep life remains a formidable scientific mystery. How do microbes spread underground? Do they descend from the surface or are they generated inside the Earth? To what depth is there life? What are your main sources of energy? Methane, hydrogen, natural radiation ...?

"Scientists still do not know how underground life affects surface life and vice versa," says Rick Colwell of Oregon State University.

Humans accumulate deep underground exploitation projects to store, for example, CO2 or to bury nuclear projects, but until now these projects considered the depths to be "globally sterile," Bénédicte Menez said. No doubt the interactions have been underestimated.

Now "there is a real awareness of this impact of life in the depths of the Earth," he adds.

The discovery also changes our perception of other planets such as, for example, Mars, where we have known for many years that there is liquid water but we are still looking for signs of life.

Knowing that at extreme levels of pressure and temperature can live some microbes "can help us look better on other planets," explains Rick Colwell, who teaches astrobiology in Oregon.

FOLLOW ME IN: @desocrates