Just last month, Switzerland became the first country in the world to ban the practice of boiling lobsters alive. But do lobsters even feel pain? In my upcoming posts, I will talk about pain in animals, what we know and what we don't know.

But first, an introduction

I've cared deeply about animals for as long as I can remember. So great was my childhood fascination that I decided to become a biologist already in elementary school. As I'm currently in the process of writing my Master's thesis in biology, that dream has almost come true. For a self-proclaimed friend of animals, however, the topic of my thesis may come across as paradoxical: pain in crustaceans. I'm torturing crabs, basically.

"You monster!" Image by D. Hazerli

Allow me a few lines to justify my actions:

- The purpose of my experiments is to find out if crustaceans are capable of suffering. If not, I've done no harm. If they do, I take solace in the fact that...

- ... the stuff I'm subjecting my crabs to is quite mild (a spray of hot water on the claw) and causes no visible injuries.

But still, why study pain in crustaceans? For one thing, many are treated harshly by humans. Lobsters are boiled alive, crabs have their claws ripped off and prawns have their eyestalks cut off to increase fertility; if crustaceans do suffer, they suffer a lot!

Crustaceans are interesting experimental subjects, because their nervous system is simpler than the ones in animals we currently believe to feel pain, i.e. mostly vertebrates (here's a review). In other words, demonstrating behaviour in crustaceans consistent with pain would lower the threshold at which we start to assume pain in animals based on brain capacity. If an animal can feel pain, it also means that it has a form of consciousness. Which is what really fascinates me the most. You and I might care about animals, but to what extent do the animals themselves care about anything?

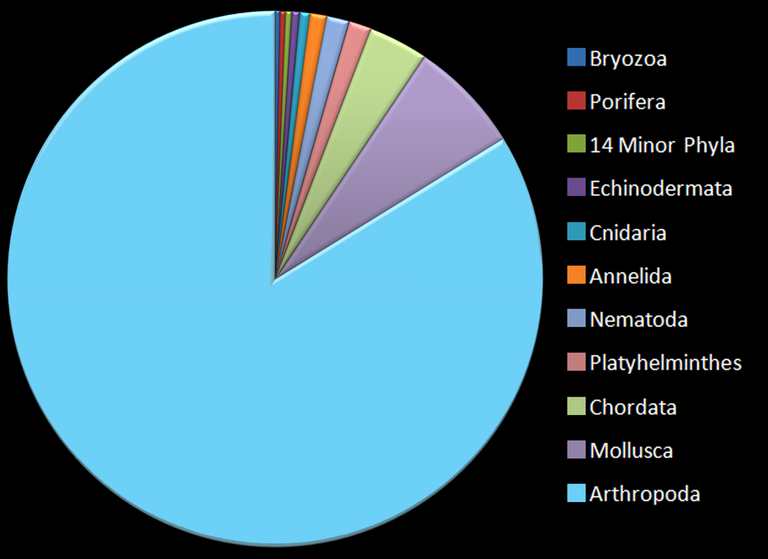

Crustaceans belong to the arthropods, the most numerous animal group on the planet, both in terms of species and number of individuals. The group also includes insects, chelicerates (e.g. spiders and scorpions) and myriapods (millipedes and centipedes). If just a fraction of these creatures feel pain, then the amount of suffering in the world is much greater than we might have anticipated.

Or maybe you've already anticipated it. A common reaction from people I tell about my research (oh, the awkward first encounters...) is this:

"But why shouldn't they feel pain?"

This is not just anthropomorphism. Several of my conversation partners note that pain is an evolutionary advantage that allows us to detect when something hurts us, so we can avoid it. This would seem to be the case for crabs and humans alike.

Nociception and pain

However, inability to feel pain does not entail failure to detect harm. In pain research, a distinction is made between nociception and pain. Nociception is the ability to record painful stimuli as sensory input. These input may be used to trigger reflex actions that require no conscious awareness. Alternatively, they may provoke pain. Pain is a subjective feeling of discomfort, something that makes it notoriously difficult to study in non-human animals (and sometimes in humans, too). To appreciate the fact that nociception is a distinct phenomenon, consider the classic case of putting your hand on a hot stove. It hurts, so you quickly withdraw your hand. Except, that's not the order of events. As you touch the stove, nervous signals travel to the spinal cord and then back to the muscles in your arm. Other signals continue up the spinal cord and into your brain where a series of brain centers collectively produce the unpleasant sensation of burning. This processing takes time, and by the time you become aware of your mistake, you've already moved your hand. What's the point in pain, then? Several options have been suggested. One of them is that pain allows us to remember harmful experiences, so we can avoid them in the future. Keep our hands off the stove, so to speak.

One way of distinguishing nociception from pain in animals could therefore be to demonstrate learning in response to a noxious stimulus. Another way is to demonstrate a motivational trade-off, i.e. showing that the animal responds differently to the same noxious stimulus, if the motivation to endure it is altered.

None of these methods are perfect. Motivational trade-offs and learning behaviour can both be encoded in a robot, a presumably painless system. Nevertheless, given that robots can even be made to mimic human pain to a great extent, there has to be a point where we accord to other animals the benefit of the doubt. A clear demonstration of learning from harm could be this point.

How do crustaceans fare in this regard? Have a look in the review I mentioned or stay tuned for my next post.

Congratulations @callimico! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Congratulations @callimico! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!