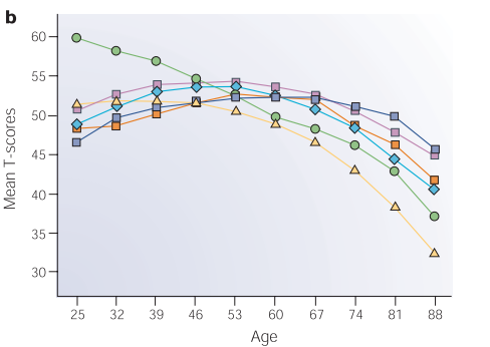

In my scientific field of cognitive aging, it is extremely common to see a figure similar to this one:

This figure represents the narrative of cognitive decline that you are most likely to hear, and in my view is an overly pessimistic one. The story goes something like this:

The trajectory of cognitive decline can be conveniently thought of in terms of Cattell’s ideas of “fluid intelligence” and “crystallized intelligence”. Fluid intelligence is composed of many cognitive domains that deal with flexibly manipulating information in novel situations without relying on previously acquired knowledge, whereas crystallized intelligence represents the ability to utilize experience and knowledge. On average, aging is accompanied by a decline in fluid intelligence starting as early as the mid-twenties. In contrast, crystallized intelligence, which relies much more on experience, actually improves with age. This is why leaders, who must rely on wisdom and experience, are typically older than their twenties.

That narrative, while effective at motivating a graduate student in their twenties like me to get busy solving this problem, may not be completely true.

This is because most of these graphs come from cross-sectional data, which means that the ages are represented by different people. Cognition is not followed across 60 years for each individual, but instead, different age-cohorts are used to find the averages of cognitive performance for each age group.

When we look at longitudinal data, a different picture appears. Longitudinal data represents data that is measured from a participant over time. The figure presented here does not have 60 years’ worth of longitudinal data, but does have much longer stretches than the cross-sectional data above

According to this figure, perceptual speed does seem to decline consistently from the early twenties. However, much of the other “fluid intelligence” cognitive domains, such as inductive reasoning and spatial orientation, continue increasing into the 50’s or 60’s. Also, verbal ability, a crystallized intelligence task, now also drops, instead of staying stable into old age like it did in the cross-sectional sample. I am partial to this longitudinal data because it gives me a bit more time to work on fixing the problem, but in truth, most likely both of these pictures are incorrect.

That is because both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs have weaknesses that bias the results of scientific studies.

Cross-sectional designs primarily suffer from cohort effects, which can be especially bothersome in aging studies. This is partially because there are large differences between age cohorts that may affect the performance on cognitive tests. Other factors may lead to non-representative cohorts. For instance, most academic institutions most easily recruit students that attend that institution. In addition, elderly subjects who choose to participate in a research study are necessarily mobile enough to make it to the experiment and likely to be engaged and interested in science, which may select for a non-representative portion of that population. Middle aged individuals who can participate in research experiments may be more likely to not have a day job that would otherwise prevent them from coming to the lab during normal work hours.

Longitudinal designs may look more convincing because cognitive performance is followed over the lifespan. However, these designs suffer from their own drawbacks. First, it is difficult to control for training effects, which will inevitably occur if the participant is frequently being tested on similar cognitive tasks. The researcher needs the tasks to be similar, so that they can compare the participant’s performance over time, but in many tasks, improvements due to practice are expected. Another issue is attrition, and particularly attrition that could be caused by some confounding factor. In aging studies, it may be more likely for an older participant who is suffering from cognitive decline to drop out of the study, thus artificially inflating the performance of the group as a whole.

Cognitive aging is not a set in stone. Whatever the true average trajectory is, recent research has demonstrated a telling and hopeful fact: that cognitive decline is highly variable between and plastic within individuals. Understanding that variability will help us strive forward towards improving cognitive outcomes in older age.

Figures from:

Hedden, T., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2004). Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(2), 87–96.

doesn't decline change person per person?

If so establishing a mean path may be not so significant

You are correct; there are large individual differences in decline. Part of the reason for the big differences between the cross-sectional and longitudinal designs are exactly because of that. The longitudinal design controls for some of that variance by looking at individual subjects over time. Probably some of the individual subjects are actually increasing in cognition or staying the same over time. Some of the individual subjects are probably doing much worse than what the figure shows. The mean paths are useful for summarizing the data as a whole and observing the overall pattern.

When scientists look at averages, they also take note of the variability in the measures that they sample. To make a significant statement about the mean, they are careful to look at the differences between means relative to the overall variability in a sample.

There are some cases where the average would not be a good way to represent the trend. For instance, it could be that there were mostly two types of people: some people continue steadily improving their intelligence throughout their life, and some people have huge and dramatic cognitive decline as they age. The average of the two may be a steady but unimpressive decline, which fails to represent what actually happens to any individual in the whole population. There are efforts to check for such bi-modal distributions, and it doesn't seem to be the case in normal cognitive aging.

nice to have some science, thanks

Thank you for the most interesting and high quality post I have read on Steemit. A good little snippet of data or research makes for a good post on platform such as this.

Attrition, which is sometimes called survivor bias, is perhaps one of toughest factors to consider when working with data such as this. Knowing this is also information and can lead to discoveries by examining why there is attrition. Statistics isn't enough when building a model but an understanding of the processes that drives the output and changes should pursued. Often referred to as the DGP, data generating process, should be known but most often isn't fully. Even some data from the FED is unusable if you don't know the origin of the data and policy changes overtime. Many data sets are poorly documented and the authors unwilling to engage in a discussion about it.

My favorite recent interesting anecdotes from research along these lines is that they had writings for nuns when they first entered the church and also know their mental outcomes in old age. Researchers say an analysis of writing of nuns who develop Alzheimers show less complexity in their than others at an early age. Suggesting the onset begins much earlier than any symptoms can be identified.

Great Post++++++

Navaman

Interesting! Did this come from one of your lit review? Lol

Just curious to know if cognitive aging is the cause of dementia and Alzheimer's and memory loss?

Haha, I'm writing the introduction to my thesis, and I thought that this part might be an interesting general topic. Your question is related to a topic that I've been thinking about doing a post about. Typically, cognitive aging is broken up into "normal" aging and "disease-related" aging. Normal cognitive aging can occur in the absence of disease, and the diseases have typical biomarkers and trajectories that differentiate them from normal cognitive aging. I'm talking only about normal cognitive aging above. So to answer your question, no, cognitive aging does not seem to be the cause of dementia and Alzheimer's.

However, some researchers have started calling "normal aging", "healthy aging", which seems like a misnomer to me. In my opinion, if someone is suffering from any cognitive decline that is related to some biological root, then that is unhealthy. I know that they're just words, so it might sound pedantic, but it's important. Aubrey de Grey has discussed the "pro-aging trance", which is the tendency to justify some normal aging processes as unavoidable, natural, and maybe even desirable. I think that if we started regarding normal age-related cognitive decline as a disease, too, (although not a terribly devastating one), we might make more progress towards its ultimate prevention.

Since dementia and Alzheimer's are usually age-related diseases, it makes logical sense to me that some of the root causes of normal cognitive aging and the diseases overlap: unhealthy vasculature, cellular damage, inefficient metabolism, weakening immune system, etc. So I do think that there is a connection between the two, even though they are separate things.

Thanks researching cracking my head on this! :-)

hey are you on steemit.chat?

How can i contact you?

Thanks for being interested in aging. You said: "I think that if we started regarding normal age-related cognitive decline as a disease, too, (although not a terribly devastating one), we might make more progress towards its ultimate prevention." Fast forward a few decades. You're in 'normal age-related cognitive decline,' or at least you hope it's that and not dementia. How devastating would it be to you?

Hi @ben.zimmerman - what a great article. As I was reading through the fluid and crystallized intelligence portion, it occurred to me that when I say "I live vicariously through others" I know that I don't have to share an experience to have an experience. For example: my sister loves to parachute. Her vivid descriptions are things that I can relate to in bite sized pieces

I know what falling feels like. I know what the wind feels like when it whips the skin on your face. I know the adrenaline rush when you think you're going to die. I can tie all those things together WITHOUT jumping out of a plane. LOL Thanks for the informative read. I really enjoyed it.

Cool, I'm glad you liked it. When did you experience an adrenaline rush when you thought you were going to die?!?!?!

There was one time when I was about 11 when lightning struck about 2 feet from me. My whole body vibrated and all the hair was sticking up. LOL Then there was one time when I was about 13 and nearly got run over by a car (I call that my divine intervention moment). A few times while being the passenger while my mother was driving (VERY close calls but no injuries). I'm sure there are more - but if I was a cat, I might nearly be out of lives. hahaha

Thanks, now I know for sure that i'm smarter now then I was in college and drank way too much beer ;).

Love this post, man!

Thanks :-)

I upvoted You