The premiere of the Netflix series Mindhunter took place two years ago. But probably not everyone knows that this production is inspired by the life of an authentic character - John Douglas, an FBI agent and later profiler who took part in the creation of the Behavioral Sciences Unit and the Investigation Support Unit at Quantico, Virginia, and who in 1995 published a book entitled Mindhunter: Inside The FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit.

I will tell you what you can expect from it - it's important, especially if you watched the show and you have certain expectations for its book prototype. I did not have - I read the whole thing and the show is just ahead of me (with some productions I'm terribly late). But first things first.

Paradoxically, Mindhunter is very light to read - although the stories described are sometimes really gruesome, and the detainers escape the assessment within the limits of common sense, this specific narrative based on digressions and even anecdotes does not allow to stay too long in one place and unnecessarily exaggerate the macabre. If in addition you know what is not about the murderers described in the book, the descriptions of their crime will only remind you of what you have already heard. What is new is the psychological profiles and conclusions of Douglas himself - and this is the most valuable part of this position.

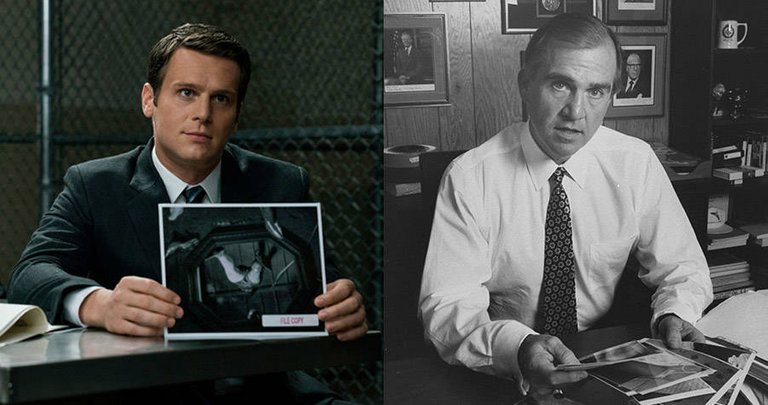

The real John Douglas is nothing like the Holden Ford from the series. The other is basically a kid, perhaps gifted with intuition and zeal, but anything naive in his innocence, an adult scout full of good intentions. His prototype, however ... well, let's just say it straight: John Douglas was not a nice guy. He starts his memories with stories from his youth, student time, an original "career" in the army and, calling things by their own names, a parade of cunning. As a man of the genre "born by political correctness," he often writes in a way that today may raise some objections. Although he does not get the same sympathy from the reader, he gives a valuable testimony of the times when it was unthinkable to hire women in the FBI, and racial segregation was an inseparable part of American culture. For this reason, it is worth remembering that this book has not been written here and now, but more than 2 decades ago, at a time when the homophobic jokes in the Friends have not yet raised public outrage.

It is not difficult to guess that if Mindhunter was made today, it would probably be more polished and avoid unnecessary controversy. Would that be better? Hard to say. John Douglas is not a doctor, scientist or professional researcher: his experiments in prisons had a strictly pragmatic purpose, so they did not have to comply with rigid scientific requirements to become useful. Douglas himself remains, above all, a man driven by the need to pursue a crime, not a cold analyst - he often lacks a professional language or scientific reference points, and the mentioned political correctness is not a priority for him. Efficiency can not be denied. And I want to say that in this context, the price for this effectiveness is not at all high.

In the world of John Douglas, the aim was to light the means whenever it was to catch a dangerous criminal and dedicate the principle of decorum to this end. Mindhunter, in addition to being a source of information about the most dangerous serial killers of America, is also a fascinating case study of the author himself and his psyche. The way in which Douglas writes about his interlocutors - psychopaths, rapists, assassins, predators hunting their victims to satisfy their drive - can sometimes arouse the reader's resistance. This feeling of discomfort forces us to reflect on how one feels and receives stimuli, someone who everyday experiences the macabre, death, perversion and cruelty that goes beyond the limits of rational understanding. Can you allow yourself to empathicly experience tragedy every time you want to be effective? Can effectiveness, therefore, absolve the traces of cynicism, black sense of humor or lack of sensitivity?

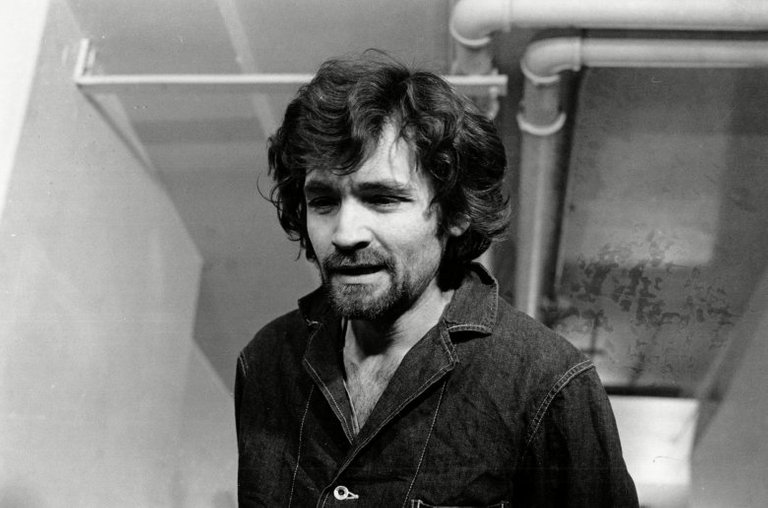

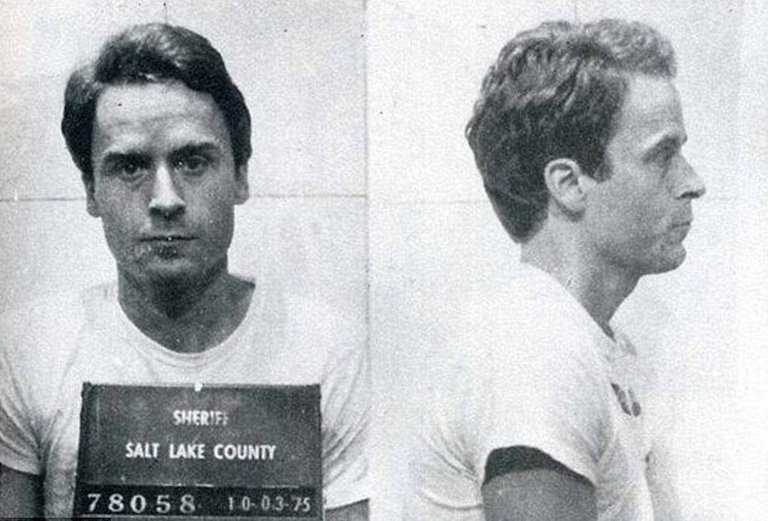

Although it requires a bit of good will, in fact it is not difficult to understand Douglas's fascination with embedded criminals. The conversations held in prisons gave the agents an insight into the psyche of people with an extremely different hierarchy of values, a sense of justice, a need for social order and intriguing needs. It is easy to bring serial killers to the level of monsters, but the essence of the difference between them and "ordinary" criminals is material for powerful professional development. For this reason, no one who is interested in the issues of psycho- and sociopathy will be disappointed after reading Mindhunter. Ed Gein (especially important for the fans of The Silence of the Lambs), Ed Kemper, William Heirens, Charles Manson, Charles Davis, Richard Speck, Jerry Brudos, Monte Ralph Rissel, Ted Bundy, Thomas Vanda - they are all here, appear in dialogues, digressions, memories, analyzes, conclusions. For many readers it will be the first encounter with these characters, which goes beyond the description of their criminal activity. Douglas goes deeper: he asks his interlocutors for childhood, home, the environment in which they were brought up, situations that left their mark on them. In some cases, these stories are just as shocking and frightening as later murders.

This does not mean, that the author did not care about the victims of the crimes perpetrated by the perpetrators. On the contrary: Douglas was often forced to distance himself from the case and focus only on the murderer, in order to make amends to the families of the murdered. With the help of psychiatrists and psychologists, he consistently perfected the workshop, learning to create a psychological profile of the criminal based on the traces left and the type of crime. This allowed him to draw far-reaching conclusions, based on many years of experience.

Mindhunter will certainly also interest those who want to learn more about the history of the FBI and the realities of the work of agents under Hoover. For me, I admit honestly, there was a great surprise about the contempt with which Hoover treated psychology and "soft science" and John Douglas's approach to clairvoyant, whose usefulness during the investigation is not undermined.

Although in the formal of Mindhunter betrays the not-so-positive influence of a bygone era in the sphere of social and world-outlook, Douglas surprises with many conclusions which, more than 20 years after publication, sound more today than it seems at the time of the book's premiere... . The most problematic issue is the determination of insanity and thus the release of the offender from the appropriate punishment and replacement of it with a stay in a psychiatric hospital. It is noticeable how much time the author devoted to contemplating this problem and trying to determine a solution that would protect society against a dangerous murderer and would justly assess the real cognitive abilities of the guilty party affected by a serious disorder.

In the end, the value of this publication is primarily determined by first-hand information and the conclusions that force us to reflect on subjects that are extremely difficult from a moral point of view. Unfortunately, this is where the lack of statistics and scientific studies begins, at least in the form of footnotes. For this reason, book is above all an interesting starting point to explore the topic and the basis for polemics to defend the pragmatic position. When an FBI profiler with many years of experience says that the most cruel serial killers are usually white, you can give him a loan of trust, but when he expresses his opinion on the effectiveness of castration rapists, you would like to ask what research and evidence is supporting this thesis outside of your own observations and intuition.

These simplifications, however, can be counted among the advantages of Mindhunter, which makes them an accessible position even for a laic and does not require reading before or professional terminology, or even breaking through the academic level considerations. Although the dilemmas that Douglas teaches are not everyday and trivial, he approaches them in a very human way, not avoiding emotions and not hiding behind any need for objectivity. It opens the way to the polemics in which it is worth entering, reaching for more items with similar themes.

Douglas also does something in Mindhunter that deliberately omits the creators of popular series of the murder: it demythologizes its heroes, deprives them of mystery and awe. This is important, especially in the context of worship, which many of them enjoy behind the prison bars. Manson, the family's inspired prophet, loses much of his charisma when he admits that he wanted to avoid another prison penalty at any price, and that was the reason he was careful not to take part in any crime personally. By provoking personal emergements and summoning the wrongs suffered in childhood, Douglas will disenchant criminals, transforming them into their own kind of pop culture idol (and I use this term with all confidence, remembering that you can buy t-shirts with Manson's face on the network) in distorted, unhappy people who in fact they are and who have nothing to offer the world, definitely not deserving of admiration, which they enjoy in some circles.

However, the question of the very formation of criminals remains complex: from a pragmatic point of view, the best method of combating crime is to prevent crimes. At what stage are we able to prevent it? Although it does not change the fact of an act of violence, can we really say that someone was born bad? How many people are co-responsible in the process of "creating" a serial killer? How many tragedies could the society have avoided if it constantly eliminated from the environment traces of pathology, violence against children, if it were more likely to empathize in situations requiring reaction, real help?

And finally, the most important: how many of us would be capable of committing a crime, even a brutal crime, if we had been subjected to psychiatric torture since childhood?

I leave you with these questions.....

From your description, Mindhunters sounds like a true compilation of horror stories, sure to change a person's view of the world. But which would you say is better, the book or the series?

I start watching the series yesterday so you have to wait for a little for my opinion about it.

Ps. I wrote that I didn't see it yet.

Posted using Partiko iOS

Hi anaerwu,

Visit curiesteem.com or join the Curie Discord community to learn more.

Congratulations @anaerwu!

Your post was mentioned in the Steem Hit Parade in the following category:

Seems the book did a better job but maybe it wouldn't receive much viewership if they had done it same as the book

Posted using Partiko Android

Maybe I just start watching the series so I will write my opinion about the show in a week or so.

But know the book is better than Netflix series.

Posted using Partiko iOS

Alright, time will tell

Posted using Partiko Android