It is believed that Pope Gregory I made his mission to Canterbury upon observing Anglo-Saxon slave children from Great Britain on the Roman slave market, which inspired him to convert them to Christianity. It is even further speculated that their blonde hair and blue eyes goaded him toward his voyage, probably for their exotic, cherubic features—as the oft attributed quote, “non Angli, sed angeli” (“They are not Angles, but angels”), would suggest—but the assertion that they were slaves and thus not fluent in the languages spoken in the area, is about as likely as Gregory I found the slaves to be.

At the close of the 6th century a.d., Pope Gregory I, while in Canterbury, expanded upon a classification of vices excerpted from Proverbs 6:16-19, named in the text as the “seven things the LORD hates”, and known familiarly as the “seven deadly sins”, as they have been complied by the Pope into the commonly known list: gula (gluttony), luxuria (lust), avaritia (greed), superbia (pride), ira (wrath), vanagloria (vanity), and acedia (sloth), later adding envy to the list, having ruled out vanity as a form of pride. The Pope’s abridgement of biblical context in such a way was almost singsong in simplicity, especially for a pre-Renaissance populace that had limited exposure to God’s Word, and has ever since been accepted as one of the cardinal principles of Catholicism, which raises concern.

In the days before the invention of the printing press and the Christianization of Europe, the capital vices may have been necessary, but now, while appointed by a Pope, has outstayed its welcome, having evolved into an extra-biblical maxim, and needn’t any adherence. Of the seven listed by Gregory I, only two sins are named in the Epistle to the Galatians as deterrents from inheritance of the Kingdom of God: wrath and, to an extent, gluttony.

(All but one of these vices, pride/vanity, is explicitly mentioned to be a sin in both the biblical and extra-biblical sense.)

The Greater Sins

Wrath

Contrary to popular belief, “wrath”, when defined biblically, is not an act of anger, in general, but sinful anger fueled by reprisal. A cause of confusion may arise from the use of “anger” and “wrath” interchangeably, especially amongst different translations of the Bible—e.g., the NIV of Ephesians 4:26 (“‘In your anger, do not sin’: Do not let the sun go down while you are angry,”) and the KJV (“Be ye angry, and sin not: let not the sun go down upon your wrath”). One could conclude that the evolution of language is the cause of the confusion, but the context of the word is consistent, regardless.

Genesis 49:5-7 reads,

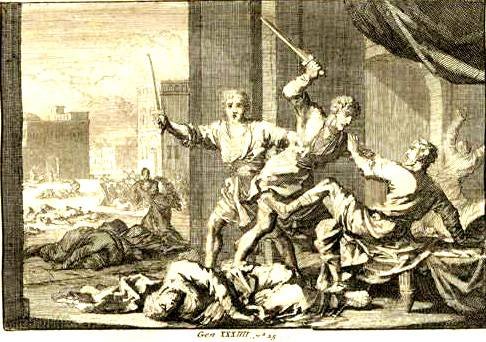

“Simeon and Levi are brothers; Their swords are implements of violence.

“Let my soul not enter into their council; Let not my glory be united with their assembly; Because in their anger they slew men, And in their self-will they lamed oxen.

“Cursed be their anger, for it is fierce; And their wrath, for it is cruel. I will disperse them in Jacob, And scatter them in Israel.

(NASB)

“Wrath” here translates to sinful anger, a reaction to the rape of their sister, Dinah, that gave Simeon and Levi the incentive to embark on a violent rampage, something that, while an act of retribution, was extreme even in the given context. However, in Ephesians 4:26, where wrath is described as a physical act, it is still encouraged that one does not acquiesce to it, lest it overtake them and drive them to commit acts of violence, as displayed by Levi and Simeon.

And yet, the same God who distinguished anger from anathema has shown Himself to be retributive through scripture. The wrath of God is unequivocal in its vengeful nature, as shown in Revelation 19:15:

Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations. "He will rule them with an iron scepter." He treads the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty.

(NIV)

The wrath, in this case, is carried out against the Beast, but while vengeful, it is an appropriate punishment for a force that is just as depraved as it is immovable. God has a flair for detecting evil and appropriately targeting it without causing collateral damage, which is why we are dependent upon Him to fight our battles.

Gluttony

Two sins listed in Galatians 5:20 are offshoots of gluttony: drunkenness and debauchery. There are many warnings, throughout the Old Testament, against excess and indulgence, but a specific passage to consider is Ephesians 5:18, which states that drunkenness leads to debauchery. These two sins are distinct in their degrees of perniciousness. It is not a sin to drink wine, but it is a sin to become intoxicated, and drunkenness will not always lead to other sinful behavior, but debauchery—in this case, orgies—is, in itself, sinful behavior. While both acts differ in their degree of injury, they both show a lack of judgment and moderation.

The Lesser Sins

Lust

It would not take much scripture to discredit lust as a sin, or at least, a deadly sin, but a nucleus to the perception of lust as a sin is Matthew 9:27-28, which reads,

“You heard it was said, ‘Do not commit adultery,’ but I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman in order to lust after her has already committed adultery with her in his heart.

Whether quoted by priests to guilt teenage boys into refraining from masturbation, or sophistically to brand human imperfections as sin by pseudo-theologians, like Ray Comfort, this passage is mistaken to be a legitimization of lust as a sin. Firstly, it is imperative that we understand that Christ came to fulfill the law, and not condemn it, while observing His citation of the seventh commandment. It seems as if he wishes to make some sort of negation, not to annul the commandment, but to annul the act as a breaching of that specific commandment; lust after a woman is not an act of adultery, but an act of covetousness.

In order for there to be covetousness, there needs to be some sort of possession of the object upon which the premium is placed. There is no claimant to a woman who is unwed. (Of course, the same principle applies for men, but men were, and still are far more explicit about their erotic fantasies than women so Christ, in his discretion, no longer made that discreet.) The sin is not lust, but lust for another’s spouse.

Why would the same God who sees barrenness as a curse and emphasizes the importance of marriage penalize us for lusting after our wives?

Envy

If anything, lust after one’s spouse is an act of envy. There is not a difference, but a distinction between envy and covetousness. Envy is directed toward a person, while covetousness, i.e., avarice the husband for having a beautiful wife, is directed toward an object. In this case, the person is the husband and the object is the wife. In a covetous mind, the woman is no longer seen as human, but an object to be desired, a prize to be won, and the husband is viewed as fortunate for having her. (I phrase this heteronormatively to annul the assertion that this idea of objectification is borne from a feminist tone.)

The distinction is expounded through the two instances of the Decalogue’s final commandment, in Exodus 20:17, (“...thy neighbour’s house...”) and Deuteronomy 5:21 (“...thy neighbour’s wife...”). “Covet” is, however, used in both passages and in nearly every interpretation. Of course, the latter is tangent to the original intention of the author, but the caution against covetousness is emphasized far more than it is against envy. Arguably, covetous thoughts are far more deleterious than those of envy.

In fact, one can even argue that envy is more healthy than covetousness. Envying what one has leads to ambition and competing, but coveting what they have leads to theft and murder, and it would not be hyperbolic to assert that it is often the impetus of war.

Greed

Greed, when juxtaposed with envy, raises many questions, especially due to it being frequently featured in arguments for Christ being a socialist.

The argument has been had and I see no point in further engaging. Just know that there is nothing sinful about keeping money that one earns. The Bible defines greed as the gaining of wealth illicitly, or at the expense of others, as defined in Proverbs 15:27 (KJV), not the refusal to share said wealth with people who on the basis that they have less. The Svengali who promises healing through witchcraft, the con artist, the crack dealer, the business magnate who lobbies for grassroots movements to cause dissension, all bring trouble to their own houses and will not inherit the Kingdom of God; they will be just as miserable on Earth as they will be in the after life. It is honorable to do good in order to become rich, but when one does bad in order to become rich, he is the one in the wrong.

If accumulating wealth serves as a detriment, why would the poor wish for it? There are more advantages to affluence than there are to destitution.

Sloth

Sloth is a stimulus of poverty, without a doubt, but in order for something to fit the candidacy as a perpetually deadly sin, it must always be a sin. In some instances a disinclination toward labor is necessary or justified, as on the Sabbath, when it is encouraged.

Just as murder is distinct from homicide, sloth is distinct from apathy, which is more spiritual, rather than physical, in nature. Spiritual apathy is a lackadaisical relationship with God. Not adhering to the liturgy is on par with not having a relationship with God at all.