Copyright Daniel Waterman, 2018.

Introduction:

This paper explores the way unresolved conflict from pre- and perinatal phases shapes social and cultural values. My premise is that religious ideas about human nature are operative in Western culture. These ideas derive from a specific interpretation of the Biblical creation myth. I want to clarify this by examining the creation myth from the subjective perspective of the child. This approach reveals the allegory of the Garden of Eden and the expulsion of Adam and Eve as a metaphor of birth and separation. This allows us to consider how our earliest formative experiences predispose us toward specific beliefs about ourselves, and how these beliefs are reproduced at the societal level. At the same time, I posit the possibility of ‘therapeutic integration’ as something implicit in an awareness of the way birth and separation shape outlook and behaviour. This awareness may empower us to distinguish between social and cultural practices that are harmful and ineffective and practices that promote health and wellbeing in their fullest possible sense.

Prelude to Transformation

Beliefs and assumptions about who we are, where we come from, what happens when we die and so on shape our ideas about the purpose and meaning of our lives and hence, the choices we make. This is precisely why society and culture have an urgent interest in perpetuating certain beliefs, especially those directly relevant to the production of power. But the interests of love, support, respect, something meaningful and interesting to do, health and justice are sometimes diametrically opposed to the policies pursued by society. This begs the question whether and what specific beliefs about human nature justify these policies. To answer this question, let us examine how theological ideas from the past translated into concrete social and cultural practices.

Theology draws on the relationship between man and God to reach certain conclusions about human nature. But those conclusions cannot be accepted a priori; many of the religious assumptions that inspired theology have been disproved or discredited. They nonetheless played an important role as a foundation for moral ideas. A critical examination of how theologians derived these moral ideas from their claims about human nature will enable us to identify distinct elements of the interpretative process. This in turn empowers us to see how these interpretations translate into distinct social and cultural realities.

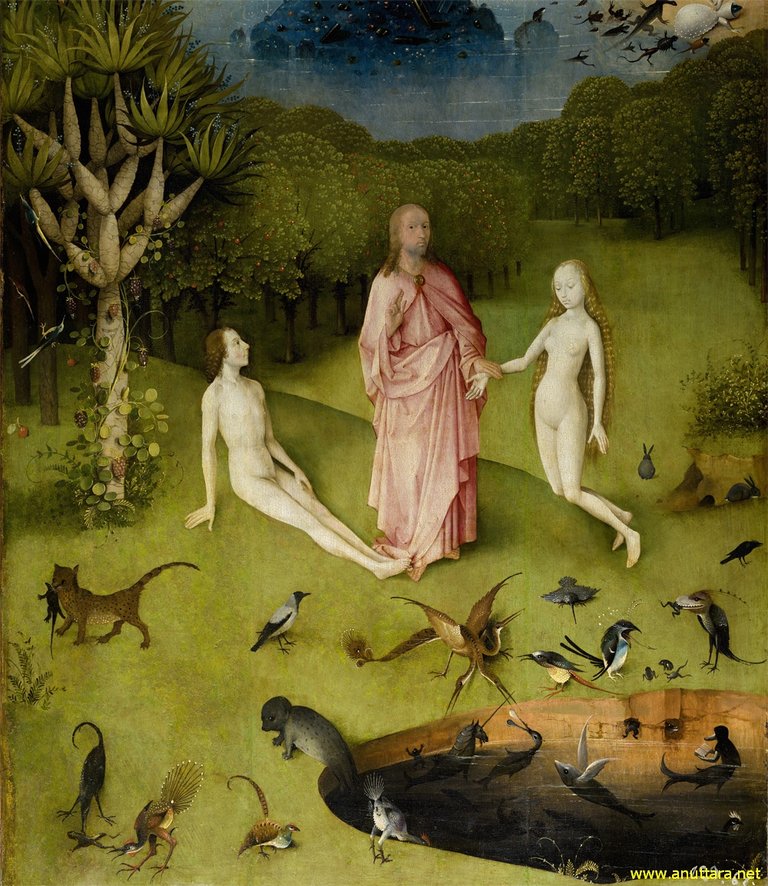

Let us adopt for a moment the perspective of a child. It is my opinion that this perspective is central to understanding the account of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden. This allegory, deals with the separation of man and God. As such, it became the basis for Augustine’s ‘Original Sin’ and thus a source of conceptions of human fallibility and corruption that profoundly shaped the Christian world.

The world as we encounter it today is, as it were, living proof of Augustine’s theological claim that man is fallible and corrupt from inception. But is the state of the world really proof that human beings are inherently flawed or evil? Augustine may have missed the point when he interpreted the eating of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge as a deliberate act of rebellion against God. If Adam and Eve were innocent prior to eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, then Augustine’s accusation makes no sense. But the eating of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge occasions a dramatic change of awareness —symbolised in a sense of guilt and shame, and ‘hiding from God’. This new consciousness signals a fundamental change in the relationship between man and God. Is this account historical, or should it be read as a metaphor?

The symbolic elements of the story of the Garden of Eden could just as easily, and with much more justification, be interpreted as referring to the womb and to birth. But this interpretation relies heavily on our ability and willingness to explore the entirely subjective perspective of the child.

This idea is difficult to grasp because most people have difficulty recalling birth, especially if it was particularly traumatic. That may be the case if something went wrong in the womb, or if a child is born to parents who don’t love and respect it, or if it experiences violence and deprivation in early life. In addition, birth symbolism and references to the subjective life of the child such as encountered in mythology, have largely been eliminated, or undergone reinterpretation in Christian theology. They have also been ignored by mainstream psychoanalytical movements. Without a positive context for this subject we are pretty on our own when it comes to identifying and exploring birth related material.

Where Augustine posited separation from God as the ‘eternal condition of Man’, I believe that the allegory of the Garden of Eden actually presents a key to the restoration of our ‘relationship to God’. This restoration can, in my view, be accomplished through the ‘healing’ or ‘integration’ of birth related trauma. This healing process significantly enhances the clarity with which we enter into dialogue with ourselves. The reason why is best summarised in the language of psychoanalysis as the elimination of unconsciously repressed material that prevents us from engaging with emotions and intuitions that we need in order to decide what is truly important to us.

It is in this sense that we must acknowledge the impact of Augustine’s legacy; the entire edifice of Western culture and thought is constructed, so to speak, on a religious account of our relationship to an external supernatural authority. This account fails to acknowledge the de facto unity of man and divine and posits in its place eternal separation. But the interpretation I have proposed suggests that this separation can be resolved by overcoming the pain, shame and existential uncertainty of birth and separation. Implicit, it this interpretation, is the notion of a restoration of the sacred union, a concept referred to in the Judaic tradition as “Tikkun Olam” or the healing of the world.

Implications:

To recapitulate, what I am actually saying is that the idea of God, or the divine, is something that points to our own deepest selves, that there is, as it were, a memory of the blissful union with our creator that draws us into a dialogue with ourselves. Pain, fear, guilt and shame act as obstacles to this dialogue. This is why concepts of good and evil, Sin and guilt are so dysfunctional. To enter into the divine dialogue within, we need to overcome these obstacles. This is easier when we actually understand what they are, where they come from and why they exist.

This idea is not new; many cultures developed some awareness of the dynamics of birth or unwittingly adopted ‘religious’ and ‘healing’ practices utilising some of those dynamics. Amongst the most powerful of these practices are undoubtedly those using psychoactive substances to produce a dramatic reenactment of birth and death. Such traditions are replete with references to the womb and to birth and this is not a coincidence. It is not a coincidence that the allegory of the Garden of Eden can so easily serve as a metaphor of birth and of the cognitive and existential transformation we experience when we are ‘expelled from the womb’ and ‘separated from our Creator’.

These cultures evolved a range of practices to promote integration. In similar fashion we could ask whether, to what extent awareness of the potential for integration might empower us in our efforts to create a more healthy and humane society.

Because our emotional needs are modelled on our earliest and most primary experiences of attachment, an inability to find a new repository for them in later life leaves us in a state of perpetual emotional dependency. Failure to identify the source of these emotional needs is thus accompanied by a failure to recognise how they can be transformed, or even that they can be transformed. Consequently, we have to accept the ‘alienated’ condition of mankind as the default. And this default mode then becomes the model for all social and cultural institutions. Awareness of the potential for integration challenges us to reimagine those social and cultural institutions as ‘midwives’ to a sort of spiritual liberation.

Copyright Daniel Waterman, 2018.

Congratulations @dolong! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!