Study suggests some ethnicities could die out in as little as 700 years

There is no more fundamental a decision one could ever face than the question of whether or not to have a child. Children can bring couples and families closer together, bring joy and meaning into one’s life, and allow parents to leave an earthly legacy long after they are gone. Bringing a child into the world is one way parents secure a type of immortality.

At least, this was how people thought about the question of children decades before we came along.

Nowadays, the discussion a couple has with respect to having children is largely centred around economic issues rather than the traditional notions of family unity and legacy. The reality of our generation is that it’s becoming more costly to live, and children are not very cost-effective.

It used to be that parents wanted to bring their children into a world that would surpass their own lifestyle. As children brought the family closer together, parents poured every financial resource they could into ensuring their children were properly educated—in turn, and although an unspoken social contract, children with means would care for aging parents when the time came for them to do so. Children used to be an investment that paid in dividends for parents, and parents had a stake in making sure that their children were as successful as they could be.

The economic realities of our generation, however, make such attitudes to having children appear old-fashioned. Gone are the higher ideals and the benefits of having children, superseded by the economic burdens of raising them and giving them a reasonable opportunity to be successful in a world that has become more demanding of us mentally. To add to these issues, government welfare and retirement programs, such as pension plans and retirement facilities, have allowed traditional attitudes of caring for the elderly to disappear.

The economic realities of our times are such that there is no real incentive to have children. Statistics gathered by governments all over the world show that this trend is real: people are getting married much later than they used to, and having children later and in reduced numbers. This leads us to the new, more significant problem of population management.

Many countries in the world, including Canada, are at a point where the population is unable to replace itself naturally through the birth of new children. This is what’s known as a nation’s fertility rate—the average number of children born throughout a woman’s lifetime. Canada’s fertility rate has been steady at around 1.6 children per woman, and although that rate is still below the replacement rate (usually about 2.1 for developed countries), Canada’s population continues to grow steadily, thanks largely to our nation’s long-held tradition of open immigration. Immigration accounted for two-thirds of Canada’s population growth from July 2012 to July 2013.

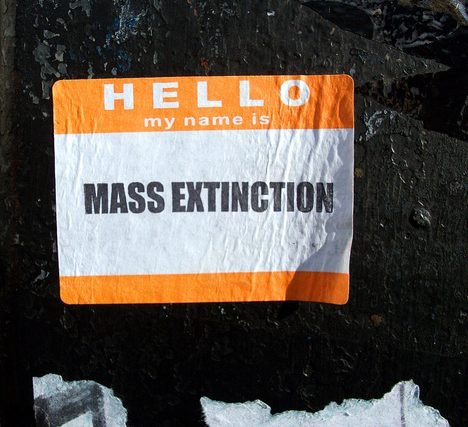

Other countries, however, are facing a real crisis which could have catastrophic economic ramifications in the future. In some cases throughout East Asia, there is even talk of a “doomsday scenario” where entire ethnicities may even go extinct if something is not done to encourage an increase in fertility.

A study recently released by the Korean National Assembly Research Service suggests that some Asian ethnicities could become extinct in as little as 700 years. The study takes a look at the fertility rates of countries across East Asia and singles out South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand as countries that need to take action to prevent a “doomsday scenario.”

Taiwan, for example, with a fertility rate that has dipped below one child per woman in recent years, will see its population begin to decline in 2022—years earlier than expected.

Calculations made in the report reveal that South Korea, with a fertility rate of 1.19, could see its population decline from 50-million to 40-million in the next half-century. Assuming the status quo remains in the next century, Korea could see its population drop to as low as 10-million by 2136—an 80 per cent drop—while ethnic South Koreans could be extinct by 2750.

In Japan, the situation is critical as there have been a number of years since 2005 when the total deaths have exceeded the total number of births. Out of a population of over 127-million, the total number of births in Japan in 2013 was slightly over one-million, while deaths in Japan in 2013 reached a post-war high, at over 1.2-million. The Korean study calculates that, assuming Japan does not take remedial action, the last Japanese person will die around the year 3011.

Hiroshi Yoshida, a professor at Japan’s Tohoku University who specializes in demographics and the economic realities of ageing populations, suggests that women’s equality movements have pushed more women into the workforce in countries that still have traditional beliefs about women and motherhood.

“These societies have reached the same level as Europe and North America in many aspects, but when it comes to balancing careers and raising children, then East Asia is very immature,” said Yoshida in an interview last week with the South China Morning Post.

The answer to reversing the path to extinction is two-fold: make it more financially bearable to bear children, and open the doors to these countries to an influx of immigrants who wish to call these countries home.

In France, for example, there is a certain honour placed on the notion of motherhood. One reluctant French mother, Corinne Maier, wrote a book discouraging people from having children and characterized France as going through a phase of “baby mania.” One Globe and Mail journalist described France as being “a place where people follow the fertility rate in the same way Americans follow the Dow Jones Industrial Average.”

France is among the leading European countries with a fertility rate hovering around the two children per woman range. It does this by offering generous benefits to women: paid maternity leaves, generous tax benefits and subsidies of $1,000 (Euros) per month for every child they have after their second. Though raising children is a terribly costly enterprise, France reduces the burden on families, allowing them to reproduce at rates which will not negatively affect the demographics or population levels of the country.

Immigration, on the other hand, which has been the model in Canada since Confederation, is not viewed in as high regard in other countries. Celebrations behind France’s high fertility rate came with a knowledge that immigration could be restricted there, where there have been racist tensions in recent years. Germany, like Canada, relies on immigration to keep its population growing, and that population growth has powered the German and European economies for decades.

While many will no doubt be skeptical that a country could ever reach that “doomsday scenario” of extinction, sudden and dramatic reductions in population levels in a country would wreak havoc on a country’s ability to provide services to its people. A growing population means more tax revenues for governments and an ability to keep those taxes low to attract immigrants and business—whereas declining populations mean higher tax burdens placed on fewer and fewer people, often by governments who are forced into cutting services to balance their budgets.

Surely, there can be no greater human interest story than that of backtracking humanity’s path to extinction. Barring a catastrophic cosmic event and assuming global warming doesn’t kill us first, governments will be compelled into looking into the issue of declining populations.

Fertility rate refers to the number of children, on average, that women in a geographical/geopolitical area will have throughout their lifetime.

Replacement rate refers to the number of children, on average, that women in a geographical/geopolitical area would need for the population-level to remain stable (i.e. zero growth).

The replacement rate varies from country to country based on the mortality rate of a country’s population. For example, the replacement rate in Canada is stable at 2.1 children per woman, and that rate is standard throughout much of the developed world. Think of it as a woman having two children, to replace herself and her husband/partner for the next generation.

However, in less-developed countries with high mortality rates (Africa, for example) replacement rates are higher. This is because infant mortality rates among girls tend to be high, so adult women need to produce more children to replace those who could not be born due to mortality rates amongst women of non-child-bearing age. Replacement rates in Africa are higher, ranging from 2.5 to 3.3, according to a 2003 study entitled The Surprising Global Variation in Replacement Fertility.