Both Thomas Hobbes and Jean-JacquesRousseau are considered contractualists, that is, they understand that society is a rational creation of man and that, therefore, there was a moment before society until the point that it was later created. This moment is called the state of nature. The state of nature is, as already stated, a moment before civil society, prior to the creation of the state (political entity), in which man lived in the fullness of his nature. The nature of man, however, is a point of divergence among contractual theorists. When we approach Hobbes and Rousseau, one of the elements that distances them the most is the notion of human nature. This disagreement is crucial to understand how the later reasoning of both led them to really different steps.

The investigation of the state of nature has in it’s character a mythological atmosphere in it’s form of explanation of the world. The conclusions and precepts depart from pure imaginative and deductive exercise, for there is, in fact, no capacity to have an empirical demarcation of the state of nature stricto sensu, but only a deductive belief of its existence. An interesting point to note is how the notion of the state of nature can be similar to the analysis of “the fall” of Adam and Eve in the book of Genesis. The notion that there was a certain nature and that a given event brought a state of being to that nature can be found in all contractualist theorists, just as it is part of the narrative of “the original sin” in the biblical plot. Contractualists, so to speak, idealize their own “Adam” and thereby base their theories on the creation of the State and civil society as a whole, investigating the motives, duties, and consequences that this individual-people-state relationship has in it’s structure.

The British political philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin points out in his essay “Two Concepts of Liberty” the existence of two types of freedom: “negative freedom” and “positive freedom”. The difference consists in the fact that, while negative freedom refers to the absence of coercion, in which there is no third party exercising power over the other, allowing the exercise of the will, positive freedom refers to the increase and adhesion of enabling power, in which the individual seeks more and more to become the master of his own path. These two conceptions of freedom were evaluated by Berlin in order to demonstrate how freedom as an abstract element may in the end represent even conflicting aspects. Freedom in Hobbes and Rousseau plays an important, role so much that, as far as the notion of human nature is concerned, and in the very functioning of civil society, understanding these two concepts is necessary in order to understand the whole process of their theories.

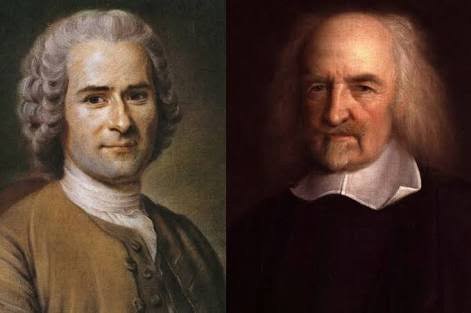

Thomas Hobbes, philosopher, mathematician and one of the leading theoreticians of modern politics, has in his career the first idealization of contractualist theory and his defense of absolutism in the work “The Leviathan”. In his reflections, Hobbes elaborates the notion of a human nature that is, above all, chaotic. Hobbes saw that all men were born the same and that in the State of Nature they were fully free. Returning to the notion of Berlin, Hobbes's natural man was endowed with “negative freedom”. There was, therefore, no legitimized entity to coerce and exert influence over the human action that had as it’s guide element, the will itself. At the same time that they were free, they were, as already quoted, equal. There was no hierarchy.

From this assumption, Hobbes understood that such a condition lay in the midst of an eternal conflict. Now if equal men are fully free and guided by their wills, at some point such wills will conflict. For Hobbes, it was not just a few moments, but it was constant. The state of war was the rule in the environment, because at all times a potential conflict could arise. Commenting on Hobbes's work in “10 Books that Spoiled the World”, ethicist Benjamin Wiker analyses the Hobbesian notion of freedom, demonstrating the sovereignty of man's instinct desire: "You are now entirely free from all internal contradiction to any and all your wishes. The walls of separation, which you used to associate with something called ‘consciousness’, simply no longer exist. As you soon realize it, once these barriers have disappeared, your thoughts and desires will roam freely through territories never known and cleared. Totally unconscious. No distinction between right and wrong, good and evil, light and darkness. The distinctions ceased to have any real meaning, or rather, they took on a new meaning. Good is all that you want and bad is what stands in your way and prevents you from achieving what you want. You are now the natural Hobbesian man, man as he truly is in his natural condition."

It is from the understanding that the negative freedom of the natural man exists to an absolute degree that Hobbes begins to theorize the emergence of the state. Starting with the fact that the state is born out of a contract in which freedom itself is partly rejected. Man, then, to leave his state of nature for having given up part of his freedom, submits himself to an absolute entity, legitimately hierarchical and capable of monopolizing for itself the use of violence. The goal? Peace. Hobbes defined the state in such a way:

"[...] a person from whose acts a great multitude, by reciprocal covenants with one another, was instituted by each one as author, so that he might use the strength and resources of all, in the manner he deems fit, to ensure peace and common defense ".

This liberty which the natural man possessed, therefore, did not bring the common good and resulted in constant chaos, the only solution being to give up such freedom, after all, as Thomas Jefferson would say: "The price of liberty is eternal vigilance." So does everyone

want to be alert and vigilant at all times? Political scientist João Pereira Coutinho disagrees, as he emphasizes in his article for the brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo "One of the great lies of modern politics is the naive belief that freedom is an universal passion. It is not. Freedom also means a burden of responsibility that not everyone is willing to bear”.

Hobbes has in his thinking two aspects: fear and hope. Categorizing the notion of freedom in Hobbes, one sees the two dimensions, for his thinking can basically be summed up as: Fear of freedom, hope in it's inhibition. May the Leviathan make good use of it!

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Enlightenment philosopher, political theorist and musician, was what can be called the last of the contractualists. He who is considered the father of the revolutionary mind, seeks to bring a new concept of “the contract”. In rejection of previous contractualists, he argues that there is a problem in the contract, which makes it illegitimate. In order to understand such a thing, it is necessary to return to the beginning, the natural man of Rousseau.

Being a contractualist, the idea of theorizing a state before civil society is a point in common with Hobbes, in such a way that it is part of his work to think a human nature and all the problematics that would lead to the artificial creation of the State, that before wouldn't exist, as all contractualists understand. Rousseau's man, however, is in fact the opposite of the Hobbesian man, for while in Hobbes man is the wolf of man, in Rousseau the natural man is in fact a sheep. Not in those words, of course, but the idea consists precisely in the understanding of a mild nature, benign and doomed to good coexistence. It's what is called the myth of the good savage: "Man is born good, society corrupts him" (Rousseau). But what does he mean by society corruption? Rousseau sees that the civilizational process was responsible for removing man from his benign natural state, where there was freedom and equality and where the good savage lived virtuously, far from the vices and problems that, for Rousseau, do not reside in human nature, but of the very structure created to escape from it.

The arts, science, and knowledge in general were, for Rousseau, the greatest representation of this process of human corruption. In his analysis of the State of Nature, the “good man” would no longer be as from the moment he came into contact with knowledge. As in the myth of “the fall”, when man eats from the Tree of Knowledge of good and evil, he knows death. The difference, however, is that for Rousseau the nature of man was only inhibited by the corruption of civilization, even in Western orthodox Christian theology, the nature of man

becomes corruption itself, and the ills of civilization are the results of nature itself, and not the other way around. And so, Rousseau saw that knowledge was corrupted, for it was monopolized by the few, thus creating the foundations of inequality.

"While government and laws promote the security and well-being of men collectively, the less despotic and perhaps more powerful sciences, arts, and arts extend flower garlands over the iron chains they carry, suffocate in them the feeling of that original freedom for which they seemed to have been born, make us love their slavery and thus form the so called tamed peoples." (Rousseau)

This monopoly made a rotten pact enforced by the lit up minority on top of the majority. The correction could come only in the distribution of knowledge and in the elevation of all to state sovereignty, creating the concept of the people as sovereign, present of modern democracy.

Rousseau here demonstrates a great appreciation for what in Isaiah Berlin's understanding is called positive freedom.

For Rousseau, there is no such thing as justice without those who do not possess knowledge, so that they may possess it in order to ascend to the realm of the exercise of their actions. His romantic vision of man was a major influence for the French Revolution and many authors still claim that Rousseau can be considered not only the father of the French Revolution but the father of the revolutionary mentality per se, who would later appear in socialist movements and the like of history.

The way both authors, even starting from the same train of thought, see the very context of their premises in a way that takes them to such distant places is of great significance. While in Hobbes there is the fear of nature itself and a negative (twofold) view of freedom, in Rousseau nature is the moral point of reference and freedom is what allows the expression of such a benign nature. While in Hobbes the sovereign is a separate being, to which men submit, in Rousseau, the sovereign is man himself. Whatever view it pleases most, it is a fact that there is a bit of Hobbes and a bit of Rousseau in each of us. Now, are we not afraid of the responsibility that liberty comes with? In time, we all desire and seek to be sovereign. It is the double freedom of Isaiah Berlin presenting his facets before minds so different and so close at the same time, bringing us the understanding of man, of freedom itself and of the State as we know it.

Victor Oliveira is a student of International Relations

Review and edit: Katarina Okorokova Façanha

Bibliography:

Bible, book of Genesis. NVI | PT, 2000.

Berlin, Isaiah - Four Essays on Liberty. Oxford University Press, 1969.

Wiker, Benjamin - 10 Books that Spoiled the World and Others Five that Helped Nothing. Translated by Thomaz Perroni. See Editorial, 2015.

Hobbes, Thomas - Leviathan or matter, form and power of an ecclesiastical and civil State.

Translation by João Paulo Monteiro and Maria Beatriz Nizza da Silva. São Paulo: Editora Nova Cultural, 1997.

Coutinho , João Pereira - O novo autoritarismo tem mais hipóteses de sucesso do que o antigo: Folha de São Paulo, 2017.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques - Of the Social Contract. Publisher Martin Claret, 2007.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques - Discourse on The Origin of Inequality. Translation by Maria Lacerda de Moura. Ridendo Edition Castigat Mores, 1754.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques - Discourse on the sciences and the arts. Ridendo Edition Castigat Mores, 1749.