Overview:

Albeit a taboo of social convention, it is irrefutable to deny the role drugs play in modern society. The war on drugs is analysed based on the approach taken by the American government, largely broken down into supply reduction measures and increased police enforcement. The ideas explored when investigating supply reduction measures are addict utility and the balloon effect hypothesis. Scrutiny of police enforcement brings us to the dealings of the potency effect. Followed by analysis of whether these prohibition methods, in fact, help or hinder the drug trade. Portugal represents the case study for being the global pioneers in drug policy. Innovative practices in tackling a drug epidemic are evaluated against policy design and outcomes. Concluding by taking a look at the crack boom with my own conjecture as to why the war on drugs is not being discarded.

Hypothesis:

This essay aims to investigate the hypothesis of whether the behaviour of agents involved in the drug trade render prohibition counterproductive.

Introduction:

In June 1971 Richard Nixon declared “we must wage what I have called the total war against Public Enemy No.1 in the United States: the problem of dangerous drugs”. Nixon followed by his successors have used instruments of repression to minimise the supply of illicit substances at the source, and increased police enforcement against users and dealers alike. The United Nations convention on drugs led to a global ban on producing, possessing, transporting and, or selling of any drug classified as illegal. Yet, despite the massive and sustained efforts of governments and law enforcement, the demand and supply for illegal drugs continues to rise. The failures of drug policy can be attributed to the lack economic intuition to think of users as utility maximising and suppliers as profit maximising. Once the effects of drug policy are considered through these channels it is evident that users will continue to get their fix and suppliers in a constant search for profit, will displace, adapting to the changing environment imposed by the government. Increasing enforcement has only ever had a negative effect on drug potency. It reduces the relative price difference between strong and weak drugs for users, and increases costs to suppliers, giving dealers an incentive to push harder drugs. Parallels can be drawn between the approach adopted by the U.S and much of the modern world in comparison to Portugal. In 1997, the number one concern on Portugal’s political agenda was that of illicit drug use. On July 1st 2001, “a nationwide law in Portugal took effect that decriminalized all drugs.” Since the law took effect the results have been staggering: a more efficient legal system, a decrease in lifetime illicit drug use among children and teenagers, substantial increases in rehabilitation treatment, as well reductions in new infections. So all this begs to ask: should we end the war on drugs?

Addicts:

Firstly analysed is the behaviour of addicts based on their utility from consumption. The strategy of reducing drug supply at the source is implemented with the intention of increasing market price to consumers, thereby reducing consumption from a simple demand and supply analysis. But once the micro-foundations of users are accounted for, success with such a policy is infeasible. Users can be broken down into three broad categories:

• Casual users, largest in number but only account for a small portion of drug consumption;

• Regular users, who use drugs for recreation or relaxation purposes, following a similar pattern of consumption, and;

• Then there are problem users.

Characteristically seen to feel worthless, and “in accordance with usual patterns of distribution, it is reasonable to assume that the top 20 percent of consumers account for some 80 percent of consumption of each drug”. A rational consumer maximises “utility from stable preferences as they try to anticipate the future consequences of their choices”. Thus, it may seem clear to any rational consumer that consumption of an addictive good has detrimental effects on future earnings and utility, implying that addiction is an antipode to rational behaviour. The beginning and resumption of harmful addictions “are often traceable to the anxiety, tension and insecurity produced by adolescence, job loss and other events” (Peele, 1985). There is an element of time inconsistency involved as experimenters will spot a serious lack of credibility in drug education. To illustrate, experimenters realise there is a probability they will not become addicts even if they consume an addictive good once more, and this continual thought pattern leads to a rational person becoming “hooked”. Once addicted, an addict, just like any other agents looks to maximise utility. Thoughts regarding the future become highly disorientated as the search for short-term pleasure makes an addict align their focus on maximising present moment consumption. In addition, the current consumption of an addictive good “depends on past consumption; incorporating the notions of tolerance, reinforcement and withdrawal” (Donegan et al. 1983) in essence leading to a discounted utility. Therefore, future consumption rises with tolerance to maintain a steady state, incorporating fear of falling below a threshold level of consumption.

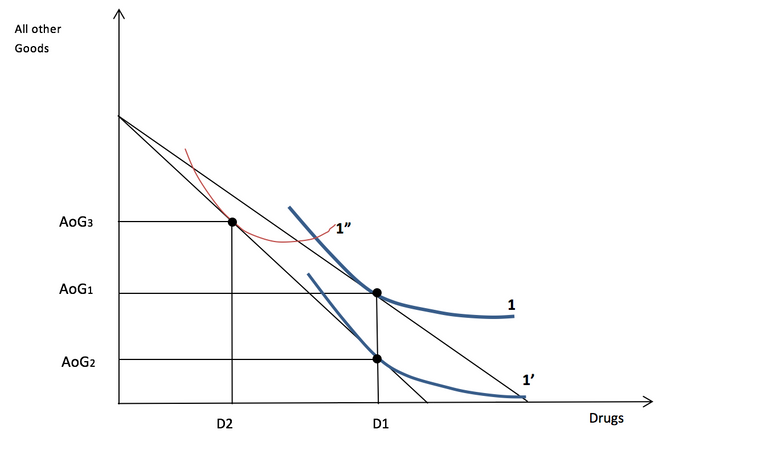

Initially, an individual is on indifference curve 1 consuming AoG1 of all other goods and D1 of drugs. The government minimises the source of supply which in turn increases the market price of drugs, pivoting the budget constraint inwards. An increase in drug price would cause a casual or regular user to decrease consumption of drugs, and increase consumption of all other goods, shifting their indifference curve upwards to 1” consuming D2 of drugs and AoG3 of all other goods. On the other hand, an addict (problem user) experiences discounted utility from consumption implying that they need increased quantities to remained satisfied. An increase in the market price of drugs will only reduce their utility maximising level of consumption. An addict’s indifference curve will shift downwards from indifference curve 1 to indifference curve 1’. At this point, an addict will significantly decrease consumption of all other goods from AoG1 to AoG2 in a trade-off to not experience disutility from withdrawal. This explains why the quantity of total drugs consumed remains constant at D1, rendering supply reduction measures ineffective. Such behaviour can be traced back to the Manchu Dynasty where opium addiction in China grew to the extent that it caused “stagnation in demand for other commodities”. It could be argued that these outcomes impose larger social costs than benefits, as the high cost of drugs induces users to commit “economic compulsive” crime to support continued drug use (Goldstein, 1985). Prima facie, a few casual and regular users will be deterred from a price increase, but, by and large the top 20 percent’s consumption will remain relatively constant. The only result being an increase in crime for a government already at war with drugs. This explains why Nobel laureate Milton Friedman famously claimed : drugs are a tragedy for addicts, but criminalizing their use converts that tragedy into a disaster for society, for users and non-users alike”.

Balloon Effect Hypothesis:

Suppliers of drugs, like suppliers of any other good, are purely motivated by profit. Realising that the highly addictive goods they supply generally have a bimodal distribution of consumption. The mode skewed towards the right forbearing addiction will not respond in mass to adverse supply shocks. In fact, it is evident that a decrease in drug supply causes black market prices to rise, only creating larger profits for suppliers. The entrepreneurial zeal of suppliers can be depicted in the notion of the Balloon Effect Hypothesis. This hypothesis states that smugglers like any profit maximising enterprise will respond to changes in cost. “If authorities get tougher on producing, trafficking or dealing in one location, the targeted activity will be displaced to another location with no more than a temporary inconvenience to the participants”.

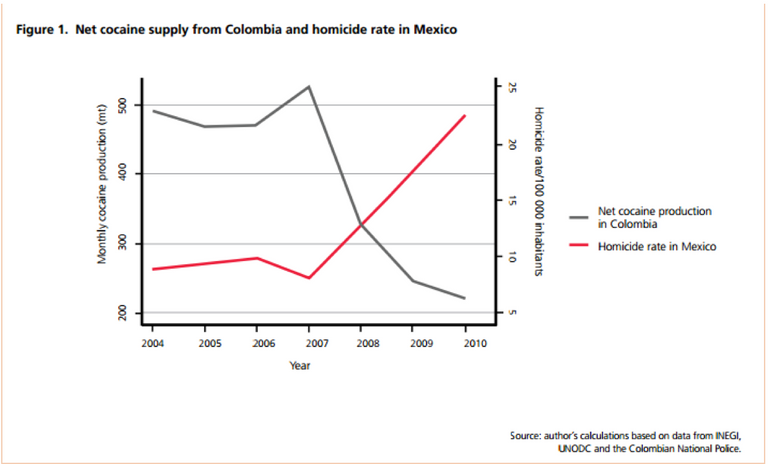

The U.S have used several measures which have only led to the development of specialists in drug production. Forced eradication of opium poppies intended to eliminate supply of the crop in most instances leads to crop displacement and, or increased cultivation. This is distinctively evident in Afghanistan; the cardinal producer of global heroin, as farmers displaced into the hands of the insurgents. Supported even further as aerial spraying of coca crops and poppy crops in Colombia pushed residents into the hands of the cartels. A fallacy of eradication measures is the belief that those at the bottom of the supply chain who inadvertently produce the majority of illicit supplies will give up their livelihoods that easily. “Failing to provide sustainable, alternative sources of income and government assistance simply motivates farmers to replant their crops elsewhere.” A war against drugs thus becomes a war against people. The use of military means to tackle drugs in Plan Colombia experienced some successes. However, as drug supplies depleted violence surged, and eventually producers uprooted elsewhere. Interdiction of drug traffickers has proven to be more successful than aerial spraying and military deployment, but once again victories in supply reduction efforts have proven to be a short-lived phenomenon. Interdiction success in Colombia in 2007 unleashed a wave of violence in Mexico that pales in comparison as drug traffickers battled for control of lucrative routes into America. The adverse effects resulting from the actions taken in reducing drug supplies can be classified as a socio-economic contagion. Displayed as Plan Columbia was discard for Plan Mexico which has seen $1bn spent by the American government since 2008; involved more than 50,000 soldiers and federal police officers, and worst of all, 47,000 drug related murders since 2006. Research finds that high-frequency shocks in the supply of cocaine from Columbian seizures caused the levels of violence in Mexico to rise. According to LSE’s report, “scarcity created by more efficient cocaine interdiction policies in Colombia may account for 21.2 percent and 46 percent of the increase in homicides and drug related homicides, respectively, experienced in the north of Mexico.” An issue for correlation vs causality as it appears the war has created the situation rather than the other way round.

Historically speaking, the balloon effect hypothesis is indisputable. The success of the “French Connection” case caused a “significant reduction in the flow of heroin into the United States from Turkey, but within three years this was substituted by heroin from Mexico and Southeast Asia” (Moore, 1990). The collapse of Pablo Escobar’s Medellin Cartel saw huge displacement. After its collapse, at least 9, perhaps 13 Latin American countries had labs processing cocaine, with 11 to 25 being involved in transhipment. The past and recent Latin American experience shows that when a country succeeds against drug production and trafficking – which is an exception rather than a rule – organizations displace to other countries where they find more favourable environments to run their operations. There is a common misunderstanding of the economic incentive of agents involved in drug production. The entrepreneurial diligence of suppliers offsets any benefits of prohibition, and can in fact lead to some very catastrophic outcomes. Highlighted more recently, as global efforts to control narcotics saw a huge triumph in 2010 with a 50 tonne seizure of safrole (a widely used precursor for MDMA). Suppliers, acting as profit maximising enterprises, simply replaced a high priced input with a cheaper alternative. This lead to the creation of PMMA, a very deadly substitute. PMMA is known to be more potent, and to take effect at a slower rate, causing individuals to consume larger quantities. The socio-economic contagion inflicted was felt in the United Kingdom as four lives were lost in the wake of 2015 from batches of contaminated ecstasy. Indeed “the Superman pill deaths are the result of our illogical drugs policy”. There is some relative success as refined agricultural products obtain a ridiculously high market price, but collateral damage to transhipment countries and the countless innocent lives impacted by far outweighs any victories seen in this war.

Potency Effect:

The tactic working in unison to these eradication measures can hardly shine in comparison. Police enforcement has played a major role in the drug target market. Legislation employed by the U.S government to criminalize users and dealers vis-à-vis the drug market it aims to disband has created quite the paradox.

Pc = C(E) + T

This shows that the price to consumers (Pc) is equal to the funds spent by the government(C(E)) to catch dealers, plus the cost levied on users (T) through reduced amenity and the threat of criminal conviction. The function of this equation, in conjunction with America’s inelastic appetite for cocaine, proved key in making criminals like Pablo Escobar the richest and most powerful of all time. Absurdly; border enforcement, interdiction, harsh penalties and possible conviction prove to be quite the barriers to entry. Only an entity with access to an extensive supply of labour and capital can dictate the drug market - at Medellin Cartel’s peak, Pablo Escobar was named the 7th richest man in the world. The function above shows it is the government that are in fact making the market profitable. If the war were to end, prices of drugs would fall dramatically to a constant unit cost matching the outcome of a perfectly competitive market. This explains why drug “traffickers demand $10,000 or more per kilogram to transport cocaine from South America to the US whereas FedEx will ship a kilogram of anything else for $60”. The central outcome from the enforcement measures has been the potency effect. On the demand side, laws prohibiting drug use reduce the relative price difference between strong and weak drugs. Alternatively, larger penalties to drug traffickers consequently increase costs, giving dealers the incentive to push harder drugs as they are higher in value and easier to transport.

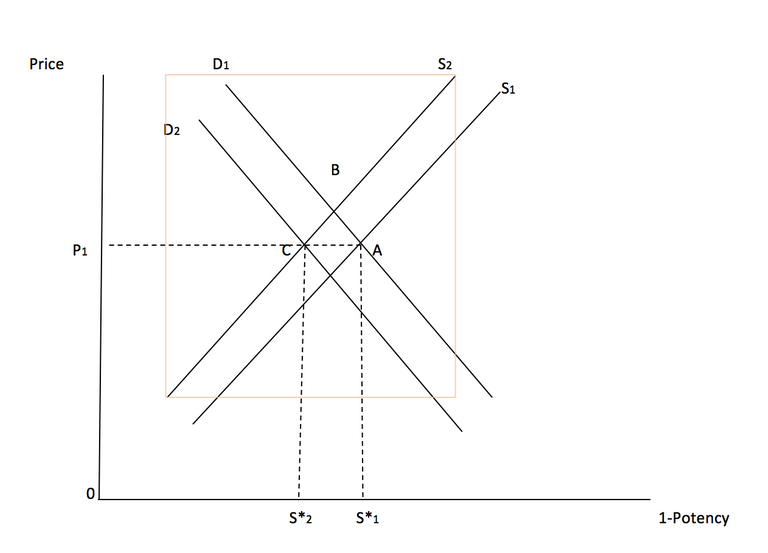

As cost to drug traffickers is a function of risk, an increase in enforcement will cause supply to shift leftward, from S1 to S2. At point B, market price and potency has increased. This coupled with increased criminal punishment that deters several casual and regular users hence shifts demand leftwards, from D1 to D2 . Inadvertently, the funds that are invested in this war, amounting to a minimum of $10 billion in 1987, led to a market equilibrium in which the price of drugs remains the same but the potency of drugs has increased S1 to S2 - in line with the claims of counter-productivity stated in the hypothesis.

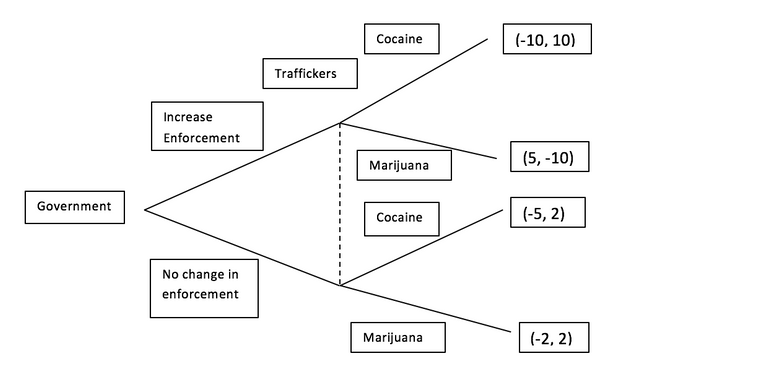

The rationale behind the potency effect can be modelled in a two stage sequential move game. With two stages and two players: The Government and Drug traffickers (1,2…,n)

At the first stage of the game the government decides whether to increase enforcement or not. If the government do not make any changes in enforcement, at the node the nth drug trafficker moves he is indifferent between trafficking cocaine and marijuana. However, if the government increase enforcement, factoring increased risk into their cost function, drug traffickers will opt to transport cocaine.

In reality, the government saw some success with marijuana interdiction against the 1st and 2nd drug traffickers, but under the notions of the balloon effect hypothesis the nth displaces. It appears that the government has lost an element of its own rationality. They should know that a sequentially rational drug trafficker will respond to any changes imposed in the environment, effectively compensating for the increased risk on marijuana by trafficking cocaine. Asymmetric information is present in this model as the media documents the government’s effort on the war on drugs, whereas traffickers will not let their output substitution become knowledgeable. Ex post the government will see the burden to society . In 1984, a drug task force fiercely increased its efforts in the Miami area, virtually eliminating the supply of marijuana. Consequently, there was a fall in cocaine prices as marijuana smugglers quickly converted to cocaine smuggling.

Portugal:

When John Stuart Mills spoke on liberty he stated “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.” Yet the Land of the Free plays hosts a quarter of the world’s prison population but only 5 percent of the total population. Reagan’s national control of the 1980s led to rapid growth in incarceration for drug offences (Blumstein and Beck 1999). The effects of criminalizing users seem hardly a deterrent, as those addicted will manage to secure drugs even in jail. Such a policy will only lead to the destruction of civil rights because the “majority of drug offenders criminal activities appear to be restricted to participation in the drug market”. The harsh consequences imposed against users under then American approach can be seen laterally in comparison to Portugal. By decriminalizing all drugs in 2001, Portugal, a country once plagued by drug addiction hardly registers the issue on the political agenda anymore. The innovative methods used to tackle drugs have put emphasis on addiction being a health problem, rather than a criminal problem. The social stigma and fear of jail under prohibition will drive addicts underground, which does not resolve the drug problem. The Portuguese process is structured to de-emphasize or even eliminate any notion of guilt. Prior to decriminalization, 60 percent of those arrested was merely for personal possession. Under the new regime, those arrested for possession of small quantities of drugs are now entitled to a panel consisting of a psychologist, a social worker and a legal advisor. Since decriminalization, Portugal has seen monumental successes. The legal system has become much more efficient - whereas America’s system is experiencing diminishing returns - concentrating on catching traffickers and giving attention to more serious crimes. The resulting arrests for drug use have fallen by 65 percent since decriminalization. Money saved in government expenditures on enforcement are now recycled into treatment programmes for addicts, which has seen an astonishing increase of 147 percent. Furthermore, lifetime drug use of any illegal drug among 7th-9th graders as well as 10th-12th graders fell significantly. In fact, “in almost every category of drug, and for drug usage overall, the lifetime prevalence rates in the pre-decriminalization era of the 1990s were higher than the post-decriminalization rates”. The victories amassed have also seen new infections including HIV and hepatitis fall by 17 percent between 1991 and 2003.

By and large, the effects of decriminalization in Portugal shift consumption to less-potent drugs, increase the use of marijuana in proportion to hard drugs and alcohol, and shifts hard-drug users towards safer practices. The conflicting outcomes of increasing law enforcement against users and dealers indicates that Portugal’s decriminalized approach should be adopted worldwide.

Are The Conspiracies True?

As the number of those incarcerated for drug offences surges, prisons become overcrowded. This consequently increases the probability of being arrested but decreasing the severity of the punishment. Moreover, as risk is induced into a suppliers costs, entrepreneurial suppliers substitute their labour to that of a juvenile, largely because juveniles are known to be risk adverse. Just as any other capitalist enterprise, those at the bottom receive the lowest wages. Foot soldiers working during the crack boom were expected to be on just $3.30 an hour which is less than the minimum wage. With a wage below the minimum, and punishment based on weight, employers in the crack industry increased employment above equilibrium, leading to several low volume pushers. America’s substantial youth incarceration rates show that even if enforcement increases the market price of drugs whilst also lowering output, the numbers in the supply side could actually increase. A priori increasing enforcement will benefit society is almost delusional, it heavily impacts labour productivity, offering a life far from prosperity. Once deemed a criminal for minor possession, an individual will be excluded from support for education, housing and chances of a career are relatively slim; posing quite the conundrum for a reformed character. With limited options, an individual is left with no alternative but to return to the drug market, “well, shit, it’s what niggers do around here to feed their family.”

The essential argument behind prohibition is that it is bad for human health and for society, but the sins associated with drugs such as crime, violence, poor living standards and spread of disease do not appear to be the outcome of drugs, but of prohibition. Strangely, no drug is as strongly associated with violence as is alcohol, and to add, nicotine has been classified as one of the addictive drugs in existence, yet both remain perfectly legal. This is “why drugs cost far more than alcohol and tobacco, not because they cost much more to produce, but because they are illegal”. Per se the high price of drugs results in crime to sustain habits and, or gang violence to reap higher profits. With their capitalist interest at jeopardy, it is no wonder why the tobacco and alcohol industry play such influential roles politically for a drug free world.

A clear cost of prohibition is corruption. “As far as crime policy and legislation, public opinion and attitudes are generally irrelevant.” However, in the case of drugs, politicians see lobbying for decriminalization as political suicide. Some politicians even have a lot to gain from the increased pool of supply. Prisons play a huge role in America economically and politically. People such as former Vice President Dick Cheney have invested millions into private prisons, highlighting how some politicians have a vested interest in the growth of the prison population. One of the most profitable prisons in America - the Corrections Corporation of America, stated in its 2005 annual report, “any changes with respects to drugs, and controlled substances could affect the number of persons arrested, convicted and sentenced, thereby potentially reducing demand for correctional facilities to house them”. Obvious discrepancies between prohibition goals and outcomes, matched with such evidence indicates that politicians advocate for a continued fight against drugs to deepen their own pockets at the expense of civil liberty. Moving on, it goes to show that the proceeds from drugs appear to fuel the world we live in. There is even evidence that suggests some financial institutes got through the recent financial crisis because of laundered drug money. Even recently, Mexican drug cartels used “HSBC, one of the world’s largest banks as their private vault”, and faced no serious government action. With corruption so widespread, the elites singlehandedly become the most vulnerable if the push for decriminalization were to be materialised. “Steps must be taken to improve the fight against anti-drug money laundering only then will the underlying problem – the staggering world drug problem – be addressed”. It is not impossible to believe some of the conspiracy theories circulating. Some go as far as insinuating that the CIA was directly responsible, or behind the emergence, and availability of crack cocaine in the United States. Theoretically, due to the success of interdiction against marijuana, cocaine flooded the market and the nominal price dropped significantly. The creation of crack cocaine was attributed to the high price of cocaine at the time, which according to evidence in Miami is false. Arguing that there is a disequilibrium of private gains and social costs, with the lust for power enacting a deadweight loss onto society.

Conclusion:

The war on drugs is a failed policy, behaviour of addicts maximising utility is an indication as to why consumption is not decreasing. It is costing the taxpayer billions to battle narcotics, and many are losing their civil liberties to the penitentiary system. No matter how tough measures get in tackling illegal drugs, it appears the police and government will simply be overmatched by the resilience of drug commerce. One would think that America would have learnt their lesson from alcohol prohibition which similarly saw increases in consumption, violence, corruption and organised crime. The only way to bring about a drug free world would be through mass bloodshed, similar to that seen under Mao Zedong’s dictatorship in the eradication of opium in China. Such methods are evidently not plausible in our utilitarian society. Portugal’s example is the direction the modern world should take. “Emerging academic consensus shows that moving towards the decriminalization of personal consumption, along with the effective provision of health and social services is a far more effective way to deal with drugs and prevent the highly negative consequences associated”. Albeit common knowledge of the atrocities prohibition brings, those in power are fixed in their stance on this counter-productive war. Concurrent media coverage has played a role in warping the public image of drug dealers and drug users to be in line with political vested interests, proving to be a major hindrance in the push for reform. It may seem more plausible that political corruption plays the biggest role in the war on drugs still being alive, because any other policy with this many failures would cease to exist. Therefore, it is beyond doubt that we should end the war on drugs.