There are some phrases that burrow into our brains and lay claim to our visions so rapidly, and surreptitiously we fail to recognize they have come to us “from with out” and not “from within.”

Some of these phrases have more historical depth than others.

Of these, the phrase “it is what it is” strikes me as being fully saturated by our "present."

Today social life is governed by a form of liberalism that is utterly exhausted but by virtue of its success as an ideology continues to shape our thinking towards social, political and economic life, despite the fact that it is incapable of coherently framing life in the 21st-century.

It is what it is, is a phrase that is made possible by an exhausted worldview. That probably sounds weird.

I’ll try to explain.

When Francis Fukuyama penned his “End of History” thesis he remarked, “the end of history would be a very sad time.”

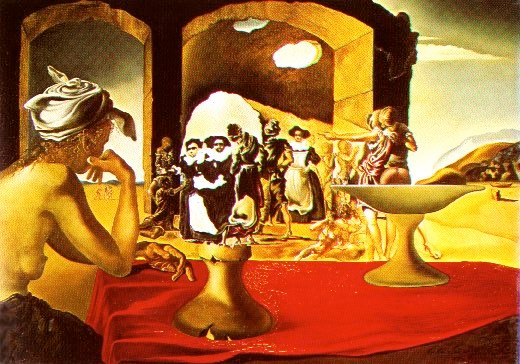

Without the dynamic tensions of different ideological world-views, liberalism against aristocratic rule, against communism, against fascism, there would be nothing left. No noble fights. No serious ideological cleavages. Just the drab continuum of a well-ordered market society. Without the contradictions of world historic-ideas confronting one another, the historic process of thesis, antithesis and negation, art, philosophy and the radical imagination would cease. (If you are interested in learning more about Fukuyama's reading of the end of history and the end of contradictions see @drrobertmuller post, https://steemit.com/society/@drrobertmuller/is-it-the-end-of-history-or-was-karl-marx-correct)

There are a number of reasons to be highly suspicious of Fukuyama’s audacious claim. The view that slavery and racism are processes separate from liberalism seems largely untenable. The claim of equalitarian conditions in the United States also chafes against those who would still advance class as a fundamental political tension animating world politics. In effect, declaring an end of history rubbed the struggles of a vast number of people out of existence.

Despite his thesis being crippled by these false assumptions, Fukuyama’s is the most honest appraisal of the real limits of possibility in liberal society and, whether we like it or not, these limits have now been reached many times over. Fukuyama was, thankfully wrong, about the end of history. Though not quite as wrong as would be comforting. The errors in his thinking have manifested in Brexit, the rise of Donald Trump, China’s decision to advance authoritarianism over democracy. These uprisings represent a highly destructive cultural malaise that is in fact the product of Liberalism’s two decades of the supremacy.

The end of liberalism came much faster than Fukuyama thought possible. In his analysis, we’d get to this moment, this moment of populism, of anti-elitism, this season of bored outrage only after several centuries. Liberalism became challenged far more rapidly than he anticipated. Why?

I think that at root, liberalism was not capable of shoring up the world delivered by capitalism’s technological progress. A smaller, hyper-connected world filled with echo chambers, filters, individualization, were too much for an ideology grounded in the 18th-century. Freedom of choice, of movement, rational debate, agency, faltered against the complex world of hyper-connected and highly differentiated relationships.

As such, I take Fukuyama’s claim seriously that by the end of World War II, atomic weapons and bombing campaigns had wiped out the material world of fascism and the recognition of the holocaust had disabled it intellectually as viable ideological force. However, the market society liberalism served to support and nurture quickly matured to the point where it outgrew liberalism. But, nonetheless, liberalism remains the dominant ideology, the "go to" when we try to make sense of what is right, fair, and moral. Liberalism’s state of exhaustion has created three features that arguably define our present.

There is a general belief that the social and political models of self-calculation that have emerged in the last three decades are the only means of attenuating intractable social problems that extend far beyond the remit of governments and politics.

A growing belief in the inevitability of failure. The ontology of the world has changed dramatically in the last two decades or so. We have moved away from a firm belief in the rational technological mastery of nature to an obsession with planning for disorder and disruption. We perpetually simulate failure not to stop it but to manage its outcomes.

Related to the second point, a general ethos that because the world tends towards failure, and adverse events, any given state of existence is shot through with ambiguity. Under these conditions, knowledge production increasingly retreats from the stable orders of classification that dominated nineteenth and early twentieth-century thought to the position that one’s social reality has no permanent state and, therefore, is beyond any system of knowledge.

If we were to analyze these conditions in technical practices and projects we would have an ever extensive and at once moving field to study named resilience. Resilience surfaces and moves across many different departments and congealing in different sites of actions, from emergence planning, financial risk analysis, military organization, to the strengthening of children in adverse social and economic conditions. Yet, the movement can be so easily conflated as dissolution and retreat that it can be difficult to find technical practices stable enough for study. After all, given the conditions outlined above a stable object and practice would be a counterpoint to the thesis rather than evidence of it.

It Is What It Is

Language is the vast repertoire of historical progress and the human condition. Old modes of life fall into disuse and disappear: the rotary telephone, for instance, now exists as a placeless thing, and the conditions of life it structured have now been unrecognizably altered. Yet we still understand what it means to “dial” phones that have no dials. Language holds dead worlds in place and can conceal new relations and conditions that have grown up from the corpses of history; after-all, when is the last time any of us really “burnt the midnight oil?”

There are also times when language does not hold the past but rather serves as the prescient form of the present. If there was a phrase that affords us some insight into the three impasses that a ruling but exhausted form of liberalism has engendered, that phrase is “It is what It is.”

For a phrase that is supposedly only a decade old, it has covered a lot of ground. I want to outline here some of the ways it has been interpreted. It becomes clear that the phrase, though perhaps not wittingly, contains within itself the ambiguity and general stasis presented by undead liberalism.

The first example comes from the experience of a military officer in his tour of duty in Iraq. It appears, this phrase was the phrase of his unit. It was spoken constantly and referred to when the military unit faced circumstances that were unfavorable.

“The problem with “it is what it is” is that it abdicates responsibility, shuts down creative problem solving, and concedes defeat. A leader show says it is what it is” is a leader who faced a challenge and couldn’t overcome it and explained away the episode as an inevitable unavoidable force of nature (we are at the mercy of the gods” (Military Leader, “Why it is a Stupid Phrase” date unknown).

Who knows if the phrase was born on the battlefield or in USA challenged by a sudden attack on home territory. Being told shortly after 9/11 by society's foremost experts and curators of the liberal order that more terrorist attacks were inevitable would no doubt create the space for such a phrase to emerge.

In any case, the phrase is an admission that the predictive, manageable world that had grown up in the alliance between liberalism and mass capitalism has been thrown asunder. “It is what it is” reveals a world that cannot be accurately predicted, a world that requires a subjectivity that must be prepared to encounter conditions that are entirely outside their personal realm of action. Agency, under these conditions is resignation. Most fascinating is that while the author of this article laments that the phrase is used as a shield against engaging in more robust problem-solving, he goes to great lengths to suggest that the phrase should not be entirely banished from our conduct and outlook on socio-political life.

“There is value in maintaining a portion of your attitude that is stoic in nature. Know what you can control and what you can’t control. And the first thing to accept that you can’t control is the past. It’s the same with life and leadership. Don’t dwell on what’s happened. Take responsibility, learn the appropriate lessons and get moving to the next objective. Doing otherwise is a distraction. Allocate your effort appropriately, not in crusades that leave your people worse off.” (Military Leader, ibid)

Hence, why it seems now that our age has seen a revitalization of the stoics. Yet, what better mentality is there for a period of time characterized by liberalism’s delegation of agency and responsibility to the atomized, abstract, rational subject? Capitalism cannot be reformed or changed; to do so would be to threaten, according to Fukuyama and his followers, the material basis of liberal ideology. Yet, without challenge there can be no fundamental engagement in the politics of recognition and struggle that continues to be defined, and in many ways accentuated, by the expropriation of labour in capitalist society. More to the point, failure, regret, and sad accidents that continually befall us in industrial mass society are to be economized by the individual.

“We’re bound to experience more failures, so stoicism teaches us to let go of that feeling of disappointment when things don’t go the way we planned. We face failure in internship and job rejections, breakups, grades, sports, family relationships and the list goes on…While our attempts to influence the world around us are susceptible to luck, failure and letdowns, the only thing at which we can fully succeed is having control over ourselves and choosing how we will react to situations.”

And, more succinctly, “Allocate your effort appropriately,” be sure to manage duress and crisis in a mode of conduct that is economically productive.

There are no other support systems, no other potential worldviews to draw upon to resolve one’s issues and if it is the case that all other ideologies have been exorcised by the triumph of the Western Idea, what remains is the rationalization of redress to ills and woes caused by the singular political terrain of the post-liberal order. The "Military Leader’s" critique of the phrase reveals the inverted nihilism contained within it; it is inverted for it consecrates the real existence of the established order but places the subject in a condition to have no power in altering these relations. It is the subject’s nihilism and disavowal of the world as a mediation of structure and agency and replaces this mediation with a top-down condition of structure on life; a relationship of power that is perhaps the most honest articulation of liberalism’s conception of the range of political action.

Yet, if this is an appraisal of the negative connotation of the phrase as a form of society that suffers from the malaise of its own triumph, we can also locate a celebratory stance to our impression of our inability to articulate worldviews capable of resolving the inevitable challenges to society. If it is the case that liberalism has worn itself out by eliminating it foes and failing to capture the cultural life presented by this current period of capitalist production, one cannot help but recognize the present state of social, economic, and political order is one of ambiguity. “It cannot last” we say. This mode of production is unsustainable and we all nod knowingly.

However, despite this phrase it is equally accepted that “it is what it is.” Meaning we recognize only the present is posed for change and disruption but will exert no efforts in making the classifications that would be necessary to guide economic and social life in new directions. The present situation is pregnant with potentiality but unlike in the 19th-century Hegelian dialects we have jettisoned any connection of this potentiality to any forward leaning social theory of development.

This abandonment of rational classification of the present in favour of a neutral appreciation of its ambiguity is given a rather glowing review in an article in "Psychology Today."

“It seems that increasingly often you hear the phrase “it is what it is” I was taking the phrase to mean, Its not this and its not that; its something more subtle that I don’t’ have a name for, and I’m ok with that. In other words, I took it to be indication that the speaking is letting the thing just exist in all its rich uniqueness without having to categorize it or analyze it. The increased use of “ it is what it is” seemed to be a sign that people are increasingly comfortable with “state of potentiality”, which are states that could collapse to different actual states depending on the context.” (Psychology Today, May 23rd, 2014, retrieved September 2016, 23).

The obvious point is that in many respects the phrase shores up the virtues often-touted as the hallmarks of the neoliberal subjectivity. No doubt, it becomes incredibly important to become tolerant for ambiguous social and economic positions in a labour market increasingly structured by the logics of flexible capitalist accumulation. One must be willing to resign themselves, if not celebrate, the passage from worker, to unemployment, from caregiver, to breadwinner potentially all within a few seasons of economic life. Equally, one must be ready to rebrand themselves to locate the potentiality in what are otherwise undesirable situations, this is indeed part of the entrepreneurial conduct that has been extended across a number of domains, to the point that these domains have increasingly become indeterminate and beyond “classification.”

However, one can also see in this autopsy of the phrase the state of liberalism today as a mode of coming to terms with the present order of relations. The author continues,

“So I was thinking of the increased use of “it is what it is” as an indication that people are increasingly resisting the temptation to force things into categories, to be comfortable with the unknown.” (IBID)

It is important not to shy away from the fact that the positive element of this attitude is the entrenchment of fluidity and spectrums of being: sexuality and gender are now considered beyond classification and also so are neurological disorders, such as Asperger’s, one is identified as being in an alternate state a different order of potentiality of experience and the push is to ensure that these states remain open without firm boundaries of classification that would limit this potentiality.

Yet, for our purposes there is also the general disavowal of knowledge production. The present order of relations is beyond classification and it is what it is, is a remark on this “fact.” If it is indeed the case that liberalism is now exhausted, unable to explain the economic or political order of our world, what we are left with is precisely a potential state of relations that are beyond our current social powers of classification. We have accepted “the complexity and ambiguity” of advanced capitalist relations and have also outlined our resignation to the “limits” of our present intellectual conditions. Under these conditions we both affirm the established order of relations and acknowledge that these conditions are unsustainable and gradually moving into yet another state. Hence, the state of ambiguity that sits at the foundation of the phrase.

It is also quite clear though that the unspoken position of the phrase is that of failure. It is not merely that we are tolerant of a continued state of potentiality that defies classification it is that our present knowledge, the categories and modes of thought we have at our disposal fail to even approximate our day-to-day social experiences.

The phrase implies our only hope at present is to resign ourselves to inevitable change that because of the limits to knowledge production, cannot be elaborated into a political or social form that we can act upon successfully. You will be disrupted, blindsided and harmed at any possible moment, successful agency is resignation to that fact.

This odd prescription is made clear in the phrase’s aloof position to questions of change. It implies ambiguity and potentiality yet also resignation to the limits of possible action. Nowhere can it imply change because to know change and articulate it, one must recognize the order that is changing. A mode of thought founded on the impossibility of classification, the possibility of knowing, renders historical development and transition unknowable. Instead, it is what it is belongs to a world that can only be understood as various states of uncertainty that are repeated over and over again. Hence it is phrase that abnegates place and time, it is a phrase that comes of age, ironically, at the so-called end of history.

"It is what it is" means the same as "A is A" or A=A. These happen to be fundamental philosophical postulates from Aristotle.

At its base those statements are objective, i.e. a thing IS itself.

Reality is what it is, NOT what you would falsely think or are deceived into thinking or believing what it is.

Thanks for commenting! I agree with Aristotle’s empiricism. If something exists than it has certain characteristics that define it and these characteristics make up its reality, whether we have the wisdom to recognize them or not. I’ve always found the challenge with this is that A=A assumes I am able to recognize A as A, which for a variety of reasons I might not be able to. Because I feel compelled to throw my lot behind a material viewpoint of the world (I.e world exists and is not a product of thought realizing itself) I fully agree. But because we also move through the world as cumbersome luminious beings and the world moves through us in both perceptible and imperceptible ways, I’ve always ended up in the critical realist camp= An objective reality exists independent of our knowledge but when it comes to social life we won’t be able to grasp its true relation and must rely on theories that are useful rather than readily true.

But anyways as the post argues, people aren’t using the phrase in the Aristotelian way but to imply ambiguity and a social order that is beyond any form of knowledge.

Awesome post! I invite you to visit our blog and enjoy our content :)

Thanks so much! I will be sure to check out your blog!