(continued from Part 1)

But Blake’s illuminations, as singular entities, still conceal the development of his thought. While they should always be sought out, it is worth pointing out that although Blake made multiple copies of each print, and the differences between them could be fairly radical. For this I would like to consider The Book of Urizen as it relates to his more major prophecy, Milton. Urizen is one of Blake’s Four Zoas, which constitute the individual parts of all humans:

Four Might ones are in every Man; a Perfect Unity

Cannot Exist. But from the Universal Brotherhood of Eden

The Universal Man. To Whom be Glory Evermore Amen

Blake’s “Perfect Unity” is Christ, the redeemer—not God, insofar as He had been understood in the Bible, and certainly not as He had been understood in Paradise Lost (more on this later). For Blake, the Zoas (sing. ζῷον) are, literally, “the living creatures” that, together, make up each and every one of us. All of them are aspects of the fallen Albion, the Universal Man, who has been divided into homo sapiens, whose psychological tendencies fight against one another on a constant basis. Each represents a basic aspect of the human—reunify the zoas would be to be redeemed, but the conflict that emerges as each of the zoas vie for dominance constitutes turmoil:

Urizen (f. Ahania)—Reason, Law, Order

Tharmas—(f. Enion)—Sensation, Tactility

Luvah (f. Vala) —Love, Passion, Energy

Urthona/Los (f. Enitharmon)—Imagination, Creativity

Urizen, the Zoa of Reason, Order, and Law, proclaims himself to be God—He writes upon his iron tablets and refuses to persuaded otherwise. In most respects, he is as close to an antagonist as Blake offers in his prophecies, and can most clearly be said to represent the institutions that Blake despised most: the monarchy, the aristocracy, and the church. In his quest to establish order, Urizen writes his laws into his “iron tablets,” and in so doing curtails the freedom of any who would oppose him.

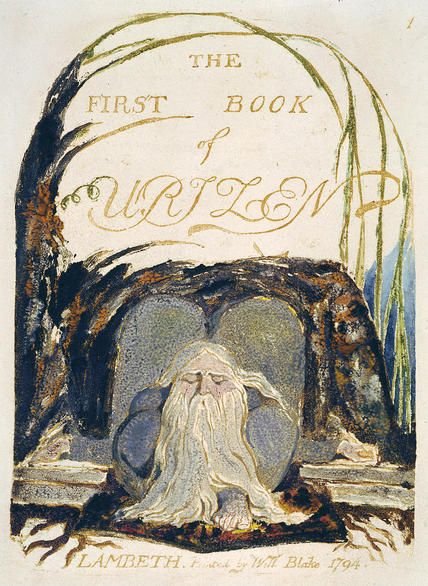

Figure 3: Frontispiece to the [First] Book of Urizen (Copy D, 1794, British Museum).

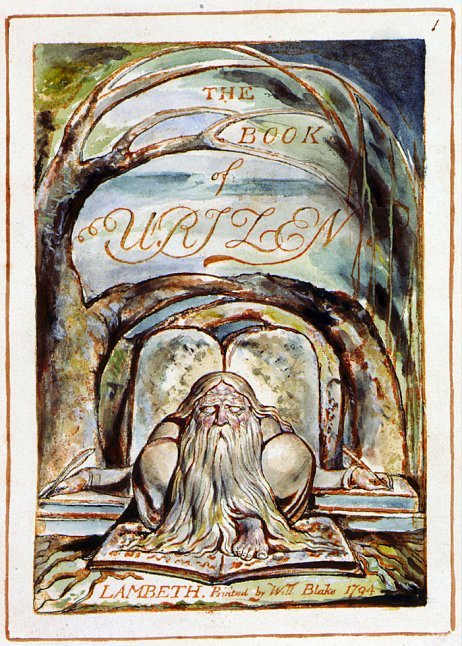

Figure 4: Frontispiece to The Book of Urizen (Copy G, 1818 Library of Congress).

Notice that when Blake began the poem in 1794, Urizen was not so clearly defined as he became in 1818—neither in character nor in artistic representation. Blake’s colors are muddled, his liniments vague, and even Urizen himself appears sleepy. Contrast that to the 1818 Urizen—In both, Urizen sits before two stone tablets that clearly evoke the Ten Commandments. But whereas Moses, a prophet of God, came down from the mountain, Urizen seems rooted to it. The very movement of Moses from Sinai to Judaea suggests, at the very least, a willingness of God to move. Urizen will not allow any such thing and buries himself deep into his own obstruction. From 1784 to 1818, however, Urizen does not move. In fact, he becomes more rooted to his own book of laws. By 1818, Urizen is firmly established and shows no sign of flexibility. The tree growing from Urizen’s tablet ultimately obscure the word “First” as it originally appeared, thus suggesting that while at one point his story might have evolved, but solidified itself into an unchanging form that was the very danger Blake suspected.

Urizen is Michelangelo’s God, brooding and imposing, with His cascading white beard and stern gaze. Looming overhead in the Vatican, he is the God who says, “Thou shalt not.” As the embodiment of doctrine and imposed law, Urizen is the shadow that obscures humanity’s view of eternity. This should not be taken to mean that he is a representation of Church doctrine or traditional, imposed religious dogma, although that certainly is part of the problem. But Blake is invoking the Urizen that is within us or the mental obstacles that prevent greater freedom of thought. These obstacles are those maxims that tell us, this is the way things are or these are the ways things should be, and with which we become complacent: these could be the results of strict religious bringing, lack of mental concepts beyond one’s current knowledge, or simply a general lack of interest. But whatever these hindrances may be, Blake was insistent that all people were capable of overcoming them, and that the value of art was its ability to rouse the spirit—which is, in Coleridge’s words, usually sleeping. This results in the subject's rousing from slumber when they openly receive the work and recognize a view of the Eternal through the lens of the Imagination. For Blake, art is, literally, a window to the infinite, and not one reserved for those of lofty minds: he intended to bring his truth to everyone, and he was sure they would find themselves open to it. As Frye writes, Blake intended to show that:

"…There is no mystery about art, and that those who insist on one are humbugs. The sense of mystery comes from a timid lack of confidence in the imagination. The best that has been thought and said, or painted, or composed, in the world, is within the reach of everyone, and those who do not possess the highest pleasures and the richest wisdom are being swindled, whether by themselves or by others (Frye 408).

But this very notion—that all people are capable of such vision—is itself obscured and difficult to comprehend, a point Blake implies visually in Jerusalem: Urizen sits brooding with his scrolls of law, but rather than the obscure markings that we see on his tablets in The Book of Urizen, we see Blake’s mirrored text, difficult to read without inversion, nonetheless states it plainly: “Each Man is in his Spectre’s power / Untill the arrival of that hour / When his Humanity awake / And cast his Spectre into the Lake” (J 41). And indeed, the message appeared to be lost on the public: while Blake felt sure that his work would be “worthy of public attention,” readers found his work far too difficult to merit its strangeness (Davis 73). His work was barely read at all, and his point entirely missed. Such is the will of Urizen:

…a Web dark & cold, throughout all

The tormented element stretch’d

From the sorrows of Urizen’s soul

And the Web is a Female in embrio

None could break the Web, no wings of fire

So twisted the cords, & so knotted

The meshes: twisted like the human brain (U VIII: 6-7)

What are we to make of the fact that Blake continually references the idea that humanity cannot understand its very ability to see the eternal, and yet continues to produce the very works he intends to send his message? Why does he bother if he knows he is incredibly unlikely to be properly understood? Given the sheer number of letters he wrote to close friends attempting to explicate his work, how could he possibly have expected the public to consider it worthy of their attention?

The answer to this, I believe, is twofold. The first lies in Blake’s tendency to proselytize, feeling it his sacred calling as a prophet to deliver his message. Given his faith that his work was of ultimate importance, he would have felt absolutely compelled to produce his illuminated books regardless of his expectations for readership. The second and more interesting reason, however, is that Blake was attempting to communicate his vision by modeling its discovery. Milton, in particular, traces Blake’s own journey through the Imagination into Eternity: Milton’s journey to the vegetated world to correct his errors (which are Urizenic in nature) represents the artist’s unique ability to open it up to glimpses of the Eternal. By using Milton to illustrate the processes of thought and vision that went into its own creation, Blake provides a symbolic roadmap for the psyche—we are invited to follow the poem and its author through the processes that went into its creation, allowing us a view of the Imagination’s vast, generative powers.

Thanks for sharing... Love it.

Thanks! still more to come and I'm glad I finally found a place where it might be appreciated.