IN THE two centuries since his passing in 1827, William Blake’s reception and reputation have undergone an almost miraculous evolution. Blake’s legacy has expanded from that of a little-known artist during his lifetime to one that enjoys some of the greatest attention and influence in its field. Deeply misunderstood by most of his contemporaries, Blake was normally thought of as an eccentric introvert at best and, at worst, and absolute lunatic. The scathing criticisms of his work include this little gem—“the conceits of a drunken fellow or a madman. Represent a man sitting on the moon, and pissing the sun out: that would be a whim of as much merit” (Davis 75)—while a more sympathetic reading of his work, from Coleridge of all people, simply stated, “I am perplexed—and have no opinion” (Johnson 499-500). He managed to earn a meager living as a printer and engraver, but achieved neither the fame nor success for which he had hoped. Just days after his death, William Blake was interred in an unmarked mass grave, along with the three other nameless men who died just before him, and the four others who died just after (Singer 1-2).

Still, toward the end of his life, Blake began developing a following of young, idealistic artists and poets, who are sometimes (and appropriately) referred to as his “disciples.” (Singer 3). His intensive creativity, the very hallmark of his philosophy, inspired a subsequent generation that would eventually play a large role in establishing his legacy—nothing was ever completed, and the very nature of his work insisted that the proper state of humanity was to be in a constant state of creation. To fix anything as “finished” would be to resign it to death. Even as he lay on his own deathbed Blake said to his wife, “Stay, Kate! Keep just as you are—I will draw your portrait—for you have ever been an angel to me” (Wilson 2). It took death itself to prevent Blake from creating anymore, but it kindly allowed him enough time to finish this one last work, the “sweet Shadow of delight,” (M:45) while leaving the rest of his massive corpus (which only he, surely, could have envisioned) unfinished. And this, as I will show, is precisely the point—Blake never considered his work finished, and would not have thought that it ever should have been. To finish a work would be to leave it static and dead; to allow it to evolve with no interest in finitude is more closely in line with the values Blake tried to communicate to those who were to come after him.

Blake’s father, James, was never one to romanticize education. He made a decent living as a clothier in London and, as was typical of middle-class merchants, had few grandiose expectations for his children. William and his brother, Robert, were mildly educated—both learned to read and write, to interpret the scriptures, to perform basic arithmetic, etc.—but were not expected to lead lives of letters, let a lone acquire any university education. But James does not appear to have been a particularly stern nor overbearing father. He wanted his children to be well-educated enough to secure financial independence, and thus prepared to groom them to inherit the family business upon his passing. William, however, began to display a passion and talent for drawing by the age of eight, and by his early teens it had become clear to James that his younger son’s complete lack of interest in the clothing business would render him miserable and, more importantly, useless. Art school, being prohibitively expensive and a seemingly a poor investment, was out of the question. Thus in lieu of formal education, William began his apprenticeship as an engraver—a modest yet respectable profession that offered the prospect of a decent living during a time when less fortunate children could hope for little more than the coal mines, the textile looms, or, portentously, the chimneys.

Blake’s training as an engraver proved to be tedious for such a radical young freethinker. Still, it was absolutely seminal for what would become the unique style and technique that characterized his mature work. Early in his apprenticeship, he would merely copy, as identically as possible, images for reproduction in books. But, of course, Blake’s true calling was that of an artist. He famously stated, “My business is to create,” and it should be no surprise that Blake incorporated his experiences and training into a new, unconventional style of artistic production (Singer 28).

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell—one of Blake’s earlier illuminated books—lays out his thinking, inspiration, and method rather clearly, though in his typically obtuse and impenetrable style. The careful reader, though, will notice that the book itself comments upon its own production through the careful hand of its author:

“But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul, is to be expunged; this I shall do by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and me-dicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid” (MHH F:14).

Here the phrase “infernal method” holds a multiplicity of connotations. In the strictly material sense, Blake’s “infernal method” involved an unusually sophisticated understanding of chemistry, albeit a very dangerous one. First he would cut a sheet of copper in the appropriate size with a hammer and chisel. Next, he would use a camel-hair brush to “paint” his designs and text (in reverse image, of course) in a solution of candle wax and oil. Finally, he would submerge the plate in aqua fortis, which would “eat away” the copper not protected by wax and oil. The result was, essentially, a stamp—the designs and texts were raised less than a millimeter above the rest of the plate, but were quite perfect for printing in the “infernal method” (Wilson 33). After printing, each design could be painted and colored appropriately. Blake understood, however crudely, that the means of his own artistic production were more in line with conceptions of Hell than with Heaven—after all, there is no widely-accepted view of Heaven that involves the literal burning away of that which is not needed.

Thus the very materiality of Blake’s illuminated books was clearly on his mind as he labored over them. If authorial intention is to be regarded as necessary to textual study and criticism, then we cannot disregard Blake’s own understanding of the way his works should be read. Songs of Innocence and of Experience, for example, exists in at least 24 known copies, each unique and printed by Blake’s own hand. Its “copy-text” may be continually anthologized, but the intended aesthetic experience is all but lost in the absence of illuminations.

On the very first page of his seminal study Fearful Symmetry, Northrop Frye articulates the problem with properly reading Blake—that it is difficult to imagine any better way of phrasing it. He writes:

"Blake is more than most poets a victim of anthologies. Countless collections of verse included a dozen or so of his lyrics, but if we wish to go further we are immediately threated with a formidable bulk of complex symbolic poems known as “Prophecies,” which make up the main body of his work. Consequently the mere familiarity of some of the lyrics is no guarantee that they will not be wrongly associated with their author. If they indicated that we must take Blake seriously as a conscious and deliberate artist, we shall have to study these prophecies, which is more than many specialists in Blake’s period have done. The prophecies form what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the language, and most of the more accessible editions of Blake omit them altogether, or print only those fragments which seem to the editor to have a vaguely purplish cast (Frye 3-4)."

And truly, it is no surprise that Blake’s prophetic books took as long as they did to come under serious consideration for, as any Romanticist knows all too well, these books are incredibly obscure. Furthermore, they are deeply intertwined with their illuminations—much more so that Songs of Innocence and of Experience, which tend to be the more vulnerable “victim[s] of anthologies” amongst his work. Poems such as “The Lamb,” “The Tyger,” and both versions of “The Chimney Sweeper” tend to be heavily anthologized, but as text-only. Perhaps the standard editorial practice is to attempt to present Blake as a relatively simple poet—I do not pretend to know, but I do know that such poems are often presented as if they are something like children’s poems. “The Lamb,” for example, certainly exhibits a certain sing-song quality that makes it seem almost a nursery rhyme:

Little Lamb who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee

Gave thee life & bid thee feed.

By the stream & o'er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing wooly bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice!

Little Lamb who made thee

Dost thou know who made thee

Little Lamb I'll tell thee,

Little Lamb I'll tell thee!

He is called by thy name,

For he calls himself a Lamb:

He is meek & he is mild,

He became a little child:

I a child & thou a lamb,

We are called by his name.

Little Lamb God bless thee.

Little Lamb God bless thee.

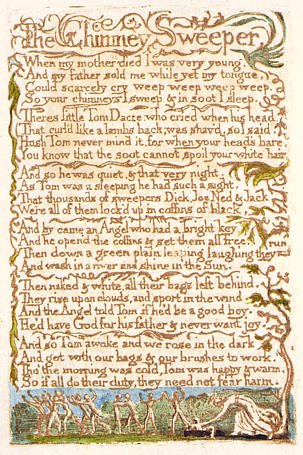

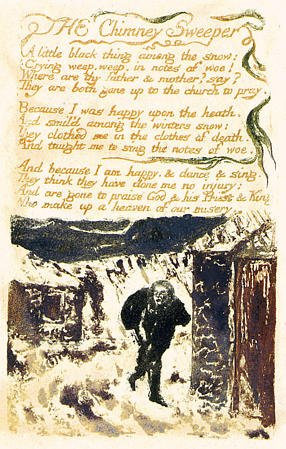

The apparent simplicity is, as always, deceptive. Even the Songs lose a profound aspect of meaning when divorced from their illuminations. Consider, for example, “The Chimney Sweeper”: Blake included separate poems bearing the same title in SIE, and together serve as one of his most notable examples of the necessary reading practices associated with his complimentary poems. The first version, in keeping with the theme of innocence, deals primarily with the dream of “little Tom Dacre,” in which he and the other chimney sweepers are visited by an angel who releases them from their “coffins of black” and promises them eternal bliss, but at a cost. The angel tells Tom that if “he’d be a good boy/ He’d have God for his father & never want joy.” The emphasis on their “duty” as chimney sweepers belies Tom’s naivety—he accepts an implicit social contract that dictates his servitude in exchange for the abstract promise of salvation. The Experience version of the “THE Chimney Sweeper,” however, is much shorter, and focuses on a child who has no illusions about the poor hand he has been dealt. This sweeper understands the hypocritical nature of this arrangement, and notes with bitter irony that while he toils at his labor, his parents have “both gone up to the church to pray,” and think they have “done [him] no injury:/And gone to praise God & his Priest & King/ Who make up a heaven of [his] misery.”

Figure 1: "The Chimney Sweeper" (C:20)

Figure 2: "THE Chimney Sweeper," (C:46)

As usual, however, readers of anthologies really only get about half of Blake’s vision for these poems. The illuminations constitute not only significant commentaries on each poem in itself but taken together illustrate the mutually constitutive nature of his works. The difference in coloration perhaps most immediately stands out—the SI version features brightly colored images of ten children being freed from their coffins by the angel and dancing joyously amongst green fields near at the foot of the image, while the SE version depicts a muted, lonely image of a single sweeper, hunching under the weight of his possessions and seeking refuge from the rain and snow. But the proportion of the imagery contributes to the poems’ meaning as well. In making the shift from multiple children playing together to a solitary child, Blake highlights the social reinforcement necessary for the sweepers’ complacency and the lonely state associated with the bitter realization of the injustice of the arrangement. More importantly, however, Blake illustrates the state of experience necessary to realize “minute particulars.” Blake distrusted the impulse to categorize everything into generalizations and stressed that careful attention to particular instances could reveal the more immediate truth. Indeed, his very typography also belies this point—his choice to style the SE version “THE Chimney Sweeper” suggests that he wanted to draw his reader’s attention to the intense specificity of his subject.