In February 1918, the U.S. Army commissioned eight artists to travel with the American Expeditionary Forces and capture the soldiers’ experience of the Great War. Among the eight artists was local Philadelphian George Matthews Harding (1882-1959) who once studied under famed artist Howard Pyle at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Army personnel believed the artists’ creations could garner public support and encourage the sale of war bonds. That idea was quickly contradicted as the artists captured the grim realities of war instead of the earlier traditions of patriotic, heroic scenes.

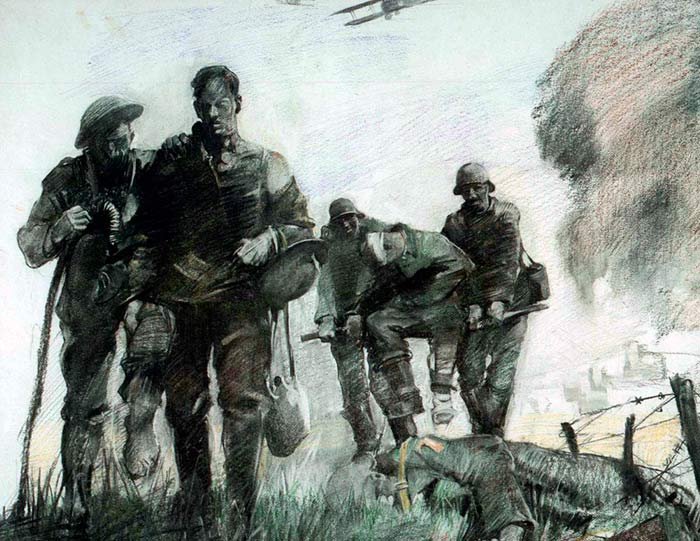

From his position in the trenches of France, Harding illustrated the new technologies of twentieth-century warfare including tanks, airplanes, and machine guns. His scenes captured the new realities of war, not the romanticized abstractions.

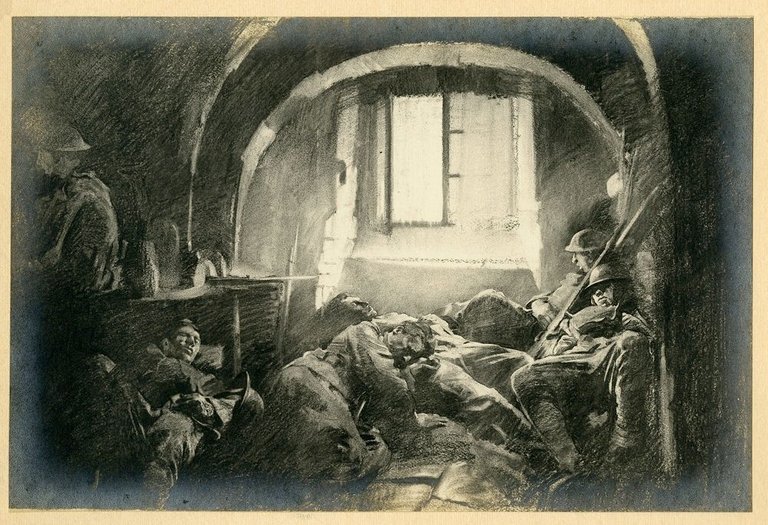

The majority of Harding’s drawings captured the everyday experience of war, and the national Committee on Public Information asserted they lacked “sufficient drama.” General John Pershing, however, approved of these accurate depictions and argued only the men serving in France could determine what qualified as “sufficient drama.” (1)

Like all the soldier artists, Harding turned the active battlefield into his personal studio. He made sketches and took notes while he experienced live enemy fire, the unpredictable weather, and the emotionally distressing elements of trench life. He referred to his “studio” as, “the loneliest place in the world.” (2)

After the war, Harding returned to Philadelphia where he published his personal portfolio including thirty-eight drawings and notes. More than 500 copies of The American Expeditionary Forces in Action were sold and exposed a larger public to the World War One experience. (3)

During the WW1 centennial, Harding’s work has recently received greater attention. Last year, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts opened their exhibit, World War One and American Art, which was "the first major exhibition devoted to exploring the ways in which American artists reacted to the First World War." The National Air and Space Museum currently has their Artist Soldiers exhibit which compares Harding's and other artist soldiers' work with the extemporaneous carvings by soldiers found throughout the European trenches.

Despite the new popularity of photography during the war, Harding's work is still relevant to the study of WW1. Why do you think the Army commissioned artists despite their subjective nature? What can this art provide that photography cannot? Are drawings more or less subjective than photography? Let me know what you think!

Resources:

- Vincent Fraley, “Artists in Uniform,”WWI Online,published June 27, 2014, accessed February 13, 2018.

- Alfred Cornebise, Art From the Trenches : America's Uniformed Artists in World War I, (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2014), 32-35.

- Ibid.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

What a lovely post. I know, that may sound like a strange comment, but the mix of word and images, ideas and information strike good notes again and again.

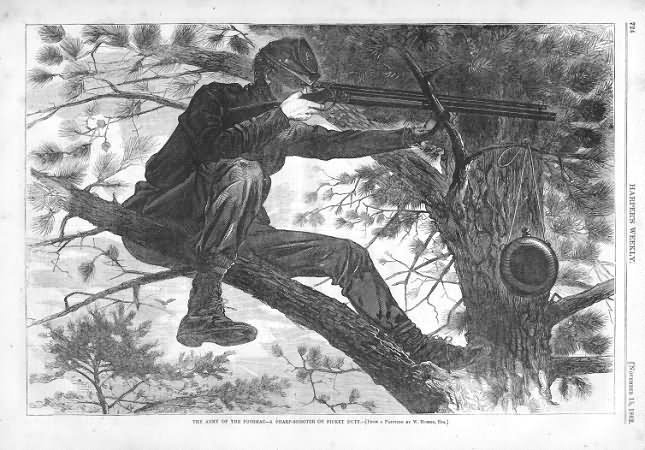

I wonder if there are aspects in common between Harding and others who created battlefield art in other wars. Like that of Winslow Homer's work for Harpers Weekly during the Civil War, where this appeared:

Thanks for the feedback!

I think the art captures feeling much better than photos could. From a technical standpoint, Harding could use colors however he wanted to, and is not limited to black and white like combat cameras would be. However he still chose to stick mostly to grayscale. Also, while photos would be somewhat distorted because of the technology, they show only what the camera captures. Harding includes tiny details in his pictures, but he still makes them fuzzy and a bit blurred--how I would expect a sleep-deprived soldier to see the world.

Agreed! Like you said, the drawings depict not only the scene but also the broader feeling. I think we tend to take photographs at face value. They are usually used to complement a larger assertion or observation. The drawings encourage questioning and more extensive interpretation.