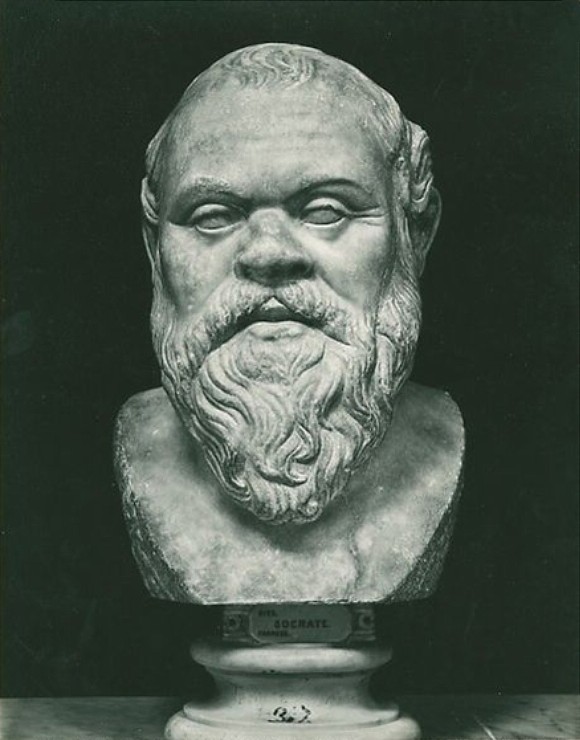

_-_n._23185_-_Socrate_(Collezione_Farnese)_-_Museo_Nazionale_di_Napoli.jpg)

If I were to compare Socrates with Plato, and I apologize in advance for the simile I am about to use, I would think to see, apparently, an ass face to face with a white horse. Why do I say this? I'll tell you.

If we bring Socrates to mind and analyze him, first of all, we see how he gives the image of being "not much", being poor, of a semblance not very pleasing to the eye and of a neglected appearance, who says he knows nothing, who covers his discourse with the most grotesque examples, always speaking - as Plato tells us in his Symposium - of "pack-asses and smiths and cobblers and curriers" so that anyone who hears him for the first time, any ignorant, any clueless person, cannot help laughing at how utterly ridiculous his speeches sound.

This is quite a different image from the one that comes to mind when we think of his disciple Plato, who was born into a family of ancestry, said to be descended on his father's side from the last king of Athens and on his mother's side from the famous lawmaker Solon, and who spoke, not like his master, of donkeys and saddles, but of the most beautiful things, such as love, justice, goodness, etc. A man who always enjoyed a high prestige, and with an influence difficult to exaggerate, so much so that it is difficult to find a comparison between ancient and modern philosophers.

Still, as luck, or perhaps fate, would have it, these two men were together.

Now we should not be fooled by appearances either, because although I said that Socrates is comparable to an ass, this is only for superficialities. Indeed, if we were to study this donkey in depth, we would see that it surpasses the best horses of the best breeds in strength, speed and dexterity.

There is something really special about Socrates, something deeply magnetic about him that arouses my interest, and not only mine, apparently, because, Socrates, with all his extravagances, generated an enormous attraction on his contemporaries. The Greek comedian Aristophanes alluded in his play The Birds to how people had become lacomaniacs (lovers of Sparta), held long hair and fasting in high esteem, and were dirty and used sticks, imitating Socrates. In fact, he invented a word to describe this type of people who lived in the same style as him.

There was a fever for Socrates, as we can see from the literary genre that arose because of him, the Socratic dialogues. These were fictitious dialogues in which Socrates appeared as the protagonist in a series of philosophical discussions. This was quite popular at the time, and of course, the most famous dialogues of this type were those of Plato. Although it is worth noting some dialogues written by a fellow named Simon the Shoemaker, who was supposedly the first to do so, and who focused on recording the real - not fictitious - dialogues involving Socrates. Unfortunately, the writings of Simon the Shoemaker were lost.

Socrates undoubtedly caused a profound change in the people with whom he interacted, and awakened a love for philosophy all over Athens and, indeed, throughout Western civilization. This can be seen wonderfully if we refer, again, to his disciple Plato, who, according to tradition, before meeting Socrates was devoted to the arts such as painting, poetry and drama (which is hard to believe if we read works of his such as the Republic, but not so much if we read beautifully written dialogues such as the Phaedrus). It is said that Socrates one day dreamed of a swan chick that, soaring through the air gave sweet songs, and the next day, upon meeting Plato said (and I'm paraphrasing) "behold the swan". Plato would change his life drastically after meeting Socrates, he would leave the arts behind and dedicate himself fully to the philosophy.

In Plato's dialogues Alcibiades compared Socrates to the satyrs, and this for several reasons. Firstly, the most basic of all was that they resembled each other physically, a resemblance we can find even in the statues made of their person. Secondly, because he said that Socrates' speeches had the same rapturous effect on people's souls as the compositions of the satyrs, which were divine.

His famous maxim expressed in the phrase "I neither know nor think that I know" was well reflected in his relationship with his disciples, whom he referred to, following ancient sources, not as "disciples" but as friends. He did not pour knowledge into them as if they were cups waiting to be filled. Rather, he asked them questions about the things they believed, awakening their own innate science, and making them challenge what they knew. He was "sterile" in terms of knowledge, but those who spoke with him experienced tremendous personal growth. These are the beautiful effects of his philosophy, which more than a doctrine or a determined set of ideas, was a lived philosophy, in words and deeds.

No doubt Socrates was an impressive man, and with a spark of divinity in him. For me, Socrates represents a rather inspiring role model who served as an example of virtue for centuries in ancient Greece and Rome, and who, despite differences, remained as such after the advent of Christianity.

He was a person who had to face the most adverse circumstances in his life until the day of his death, and yet he lived up to it, demonstrating the character of an entirely spiritually developed man. Lover of wisdom, devoted to truth, always philosophizing, conversing, seeking knowledge, assisting others to find their own path to truth. He is venerable.

This is my eulogy to Socrates, which does not do him justice, being that I leave many things out and unmentioned, and which, nevertheless, aims to awaken the same interest and the same admiration that I have for his figure in anyone who passes his sight through these words.

I think that, too. Your text inspired me to search for sources who dealt with the fact that Socrates were found guilty of breaking the universal belief of that time and why he did not acknowledge the courts decision and drank the poison from which he died. While he could have chosen to accept either being banned or pay a fine. I found Hegel as a quite impressive source who investigated Sokrates case:

https://hegel-system.de/de/v33311223tod.pdf

I am now to translate some of it into English and will provide you with it, if you like.

Thank you for the source of inspiration!

Yes, as far as I know, he would not accept any other penalty, because he did not plead guilty. If he was not guilty, he did not have to be punished, even if it was a lesser penalty. Accepting guilt, for him, would be like lying, and that is something he did not do. It also would be like contradicting the whole philosophical life he led.

That would be great, if it's not too much trouble.

Thanks to you for stopping by!