MAN AND THE MEASURE OF ALL THINGS; THE SOPHISTS

BY

Introduction

From antiquity till date, man has continued on an endless quest to discover and provide answers to fundamental questions that bothers around the nature of the world, the nature of his existence as an individual and the nature of his existence as a living being in the world (Wogu, 2010:67) captures this point when he noted that “one thing that is sure is that people who lived in the past must have been driven by a desire to explain the world and the things or phenomenon around them”. In antiquity, the most puzzling issues amongst thinkers then include: “What are things really like? How do changes in things take place? These basic questions were some of the questions that they had to grapple with. It is interesting to know that the explanations they offered to these questions became what was dubbed Philosophy - the love of wisdom. The origin of all these speculations came from the realization that things are not really the way they appear or what they seem to represent to the one viewing them. The realization that appearance after all, differed from reality- the phenomenon of growth, birth, death and decay- fully manifested in the coming into being and the passing a way of life into death, was one puzzling issues that thinkers could not help but attempt to find answers to. For (Stumpf, 2003:5-6), “these facts raised sweeping questions of how things and people came into existence at different times, and pass out of existence only to be followed by other things and persons”. We wish to note that the many answers given by these ancient thinkers in response to the bugging question of their time were not really considered as important as when compared to the fact that they attempted to offer scientific answers to these bugging questions in the first place. Examples of these attempts were contained in the mythological answers giving by Homer and Hesiod.

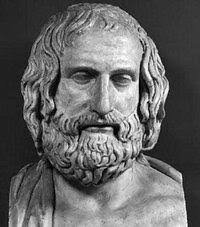

Protagoras and The Sophist’s Philosophy

Protagoras Doctrines or philosophy can be identifies in three distinctive specific areas: The Orthoepeia, The Man-measure statement and Agnosticism. Rather than become one of the educators of his time, who offered specific and practical training in rhetoric or public speaking for money of some other kind of reward, Protagoras attempted to formulate a reasoned understanding of a wide range of human phenomena, including language and education. He is also known to have had an interest in “orthoepeia” - the correct use of words, although this topic was more strongly associated with his fellow sophist Prodicus. In his eponymous Platonic dialogue, Protagoras interprets a poem by Simonides, focusing on his use of words, their literal meaning and the author's original intent. This type of education would have been useful for the interpretation of laws and other written documents in the Athenian courts” (TIEP, 1995:15-23) He was also known to have said that “on any matter, there were often two arguments (logoi) opposed to one another. According to Aristotle, he was criticized for having claimed to "make the weaker logos stronger (ton hēttō logon kreittō poiein)". (TSEP, 2012). Of all his teachings and sayings, he was most famous for this saying: "Man is the measure of all things: of things which are, that they are, and of things which are not, that they are not".

The Socratic Philosophy

The Delphi Oracle is said to have confirmed “pronounced” Socrates as the wisest man on earth. The proclamation of the oracle at Delphi, studies reveal, had immeasurable influence on the life of Socrates. Confirmed to be the wisest man that was living on the face of the earth, Socrates spent the rest of his life with one mission in focus; which was to confirm or refute the proclamation by the gods. Consequently, Socrates went out, armed with the dialectic method as one of the major tools for achieving his assignment. Socrates did not merely engage in sophistry, he was not interested in arguing for the sake of arguing; rather he was poised to discover the essential nature of Knowledge, Justice, Beauty, Goodness, and especially, the traits of a good character such as Courage. Burrell describes “The Socratic Methods” as a methodology which have been classified as a dialogue of search, “it is a straightforward but unsuccessful discussion as to how knowledge should be defined, for though it shows what knowledge is not, it fails to discover what knowledge is. But though in the characteristic Socratic fashion, it reaches only a negative result,” (Burrell1932:27-41) the argument is conducted with such skill that, as Professor Taylor puts it: "It is not too much to say that after more than two thousand years, the ultimate issues in "Epistemology" are still those which are expounded with unequalled simplicity in the Theaetetus, the best general introduction to the problem of knowledge ever composed." (Taylo, 1974:56) This is high praise, but it would be underrating its value to regard it merely as an epistemological essay in the conventional sense: for it is something much more important than the review and refutation of certain inadequate theories of knowledge or than the positive suggestions which are thrown out in the discussion.

The Measure Of All Things; A Critical Reflection

Man’s quest to interpret man in the best possible way continues to reveal that most thinkers who undertake this task do so in terms of already accepted views of the nature of man. Others base their interpretation of man on certain theories of nature already adopted by men as a result of certain inclinations or orientation which is often tied to a particular school of thought. It is therefore not necessary to argue that there is a relation, for to those who, like the Sophists of Greece, holds that “Of all things, The Measure is Man” (Jean,2004:56-65) either in ethics or epistemology; and to those like the Marxists who make economic struggle the key to human history; or even to those who like Plato conceive of a world of Ideas to which the theory of man must conform; the pragmatist Dewey, speaking in terms of biological adjustment, defines history and knowledge in terms that make central his concept of man.

Criticism of the Theory

Burrell (1932) identified three simple criticisms that we find quite interesting in a study he made on the Greek sophists. We shall be adopting these theses criticism for the discussion we wish to make in this part of the study.

(1). The Fist argument we wish to consider here is of the nature of argumentum ad hominem. It is surprising that so clever a man as Protagoras did not see that he proved more than he intended, for according to his theory, not only are all men - the wise and the foolish - reduced to the same level, but on the plane of sentient experience, it is just as true therefore to say that a pig or a tadpole is the measure of all things.

(2). Another careful look at the maxim seem to completely stultifies Socrates' arts of midwifery and the whole practice of dialectics, for in Socrates opinion, it is utter nonsense to investigate and try to refute another's opinion, when every man's opinion is correct. The question that we can’t help asking therefore is, “Is the "Truth" of Protagoras truth, or is it only a sort of solemn jest”? The Protagorian perspectives about the gods and their existence; to a large extent, have not helped his cause in the ‘man measure’ maxim… which is considered a major proponent of agnosticism, he was known to have beenof the opinion that: “Concerning the gods, I have no means of knowing whether they exist or not or of what sort they may be, because of the obscurity of the subject, and the brevity of human life” (TIEP, 2008). This position about the god and the limitations of man punctures his claims about the place of man in the ‘man measure’ maxim. This further gives us reasons to equate the entire maxim by Protagoras alongside the famous theorem in philosophy which holds that: “Knowledge is Perception”.

CONLUSION

In a similar instance, we may ask: “Is my knowledge of a thing just the same whenever I see it a yard or a mile away, does it matter whether I see it dimly or clearly, and so on. Obviously, these above instances seem to knock the base out of the theory and to prove that the theorem which invariably declared error to be impossible is itself erroneous. closing, we in identifying the degree of success achieved by Socrates in the attack on Protagoras’ ‘man measure’ theory, we can note that his argument against Protagoras could be described in modern terms as a triumphant exposure of subjectivism, relativism, pragmatism, or whatever be the fashionable name for plausible and shallow skepticism. In the Platonic language, it might be described as a duel between dialectic and rhetoric, appearance and reality, being and becoming or between sophistry and philosophy. In Socrates' own language, it is a demonstration that the "truth" of Protagoras is untrue. Perhaps it might be appropriately described as the most brilliant exhibition in the Platonic dialogues of the Socratic Method in the act of vindicating its own validity. Aristotle, with his customary penetration, has analyzed it into its elements as contained in his wellknown passage (Plato’s Metaphysics, 1978:24) he says that "two things may fairly be ascribed to Socratesinductive arguments and universal definition, both of which are concerned with the starting-point of knowledge."

References

Burrell, P. S. (1932), Man the Measure of All Things: Socrates versus Protagoras (I) Philosophy, Vol. 7, No. 25 (Jan., 1932), pp. 27-41Published Cambridge University Press on behalf of Royal Institute of Philosophy : http://www.jstor.org/stable/3747050 . Accessed: 08/11/2012 09:26.

Jean, D. M. (2004), Rhetoric, The Measure of All Things. MLN, Vol. 119, No. 1, Italian Issue Supplement: Studia Humanitatis: Essays in Honor of Salvatore Camporeale (Jan., 2004), pp. S56-S65Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3251824 .Accessed: 08/11/2012 09:16Your

Kattsoff, L. O. (1953), Man is the Measure of all Things, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 13, No. 4 (Jun., 1953), pp. 452-466. Published by: International Phenomenological Society.

Laszlo Versenyi (1962). Protagoras' Man-Measure Fragment. The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 83, No. 2 (Apr., 1962), pp. 178-184. The Johns Hopkins University Press.: http://www.jstor.org/stable/292215 .Accessed: 08/11/2012 09:21.

Osimiri, P. (2011), “The Sophists, The golden era of wisdom and The mediaeval period of the church fathers of faith and reason in philosophy”. In Wogu, I. A. (ed). A Preface to Philosophy, Logic and Human Existence. Ota: Lulu Enterprise Inc.

Plato, (1974), Theaetetus “Perception is always of that which exists, and since it is knowledge, cannot be false." And i6oC: "Then to me my perception is true, for in each case it is always perception of what is for me.".p 512.

Plato, (1978). Plato’s Metaphysics, I978b, 24.