Le Deuxième Sexe (or The Second Sex) (1949) has come to be accepted as a pioneering and uniquely ambitious attempt to explore, within a philosophical framework, all aspects of woman's situation (McCall; 1979).

The following article does not talk about women's condition in today's society. Instead, it seeks to summarise some of the most important points present in Simone de Beauvoir's work and expose the French woman's condition in the pre- and post-war years.

In over seven hundred pages of analysis, de Beauvoir scrutinises facts and myths concerning women's lives

by using the disparate methodologies of literature, history, biology and philosophy to examine

(I) problems women encounter in society; and (II) what type of possibilities are open to them (Bair; 1989).

One of de Beauvoir's concerns is that 'many men will affirm that women are the equals of

man and that they have nothing to clamour for. [However], at the same time, they will say that

women can never be equals to man and that their demands are in vain. It is a difficult

matter for man to realise the extreme importance of social discrimination' (de Beauvoir; 1949).

According to the French author, since the beginning of time, man appears to have had a dominant position not only in public life, but also in private, perhaps, undermining the strengths and abilities of women.

For instance, during Marshal Petain's Vichy regime, women's role had been diminished even more: women were encouraged to do their 'duty' as mothers by repopulating France. In October 1940, during its campaigns to return women to the home, the regime introduced legislation forbidding certain categories of married women from working in the public sector (Gorrara and Langford; 2003 : 84 – 85).

'This world has always belonged to males' states de Beauvoir (1949) in the first chapter of her History section of Book II of The Second Sex. If women truly had equality with men, society would be completely overturned (Jardine and de Beauvoir; 1979 : 227).

In fact, Beauvoir's statement 'l'humanité est mâle', is not normative, but historically descriptive. That is to say, she does not mean mankind is or should be masculine, but rather, that man (half of humanity with a public voice) has traditionally defined mankind in his own image. Therefore, she adds: 'l'homme definit la femme non en soi mais relativement à lui' (Fabijanic; 2001 : 465). For this reason, according to de Beauvoir, even 'the most sympathetic of men [can] never [be able to] fully comprehend woman's concrete situation' (1949).

Thus, the relation between woman and man is not symmetrical (Beauvoir, 1993; Heinäma, 1999): throughout history,

woman has always been man's dependant, if not his slave. Therefore, the two sexes have never shared the world in equality (Beauvoir; 1949). In the Introduction to The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir asserts that woman's legal

status is nowhere the same as man's; even her rights are 'legally recognized in the abstract'.

Men also appear to have the right to a better job, to higher wages, and generally have more opportunity for success than their new competitors in fields such as politics, economics, industry, and other relevant spheres of society (de Beauvoir; 1949).

In practice, the man-woman dichotomy can be associated with that of reason-feeling.

In exploring the history of symbolic conceptions of masculinity in ancient Greece, the Renaissance, and the present, one

finds that oppression of women is integrally linked to the traditional tie between masculinity and reason (James, 1997; Lloyds, 1984).

Bearing in mind the previous points, these social discriminations seem insignificant, yet produce in women such profound moral and intellectual effects that 'appear to spring from their original nature' (Beauvoir. 1949).

Before explaining the meaning of 'original nature', it is necessary to understand that throughout history women have occupied an underprivileged, disadvantageous position relative to men, somewhat like a minority.

In existentialist terms, the French thinker, believes that in society, men are treated as subjects, existents, as transcendents, whereas women are treated as objects, as immanents. Man is the Self: progressive, creative, able to live his own life with no restrictions.

Instead of acceding to 'subjectivity' - which de Beauvoir considers to be the source of all freedom and value - women find themselves cast into the role of subservient object, cut off from an empowering autonomy and pressed into the role of supporting male subjectivity and becomes the *Other8 (Mangus; 1953) (Plain and Sellers; 2007).

For these reasons, the realisation of her being 'other' provokes in women a sensation of discomfort and discrimination that derives from her 'original transcendent state: girls growing up, are passively taught by society how to be women consigning to oblivion the fact that woman is a free human being mystified into believing she is confined to particular roles, thus limiting freedom. Throughout the concepts of virginity, fecundity, femme-fatale, Holy Mother; the

cult of 'feminine' or 'feminine mystery' is used to mantain the oppression of women whilst the

idea is passed down from generation to generation (Scholz; 2008) (Plain and Sellers; 2007).

In an interview with Alice Jardine, de Beauvoir states:

'as soon as a women refuses to be perfectly happy doing the housework eight hours a day, society has a tendency to want to do a lobotomy on her. Therefore, considering that most women follow a routine, it is possible to take away their spirit of revolt, of debate, of criticism, and still have them perfectly capable of making stews or washing the dishes'** (Jardine and Beauvoir; 1979 : 229).

In addition, they live dispersed among the males to whom they are attached through residence, housework, economic

and social conditions. In essence, they have no past, no history, no religion of their own (de Beauvoir; 1949): Western society conditioned women to become wives and mothers and made those who rejected those roles feel somehow inadequate and incomplete (Patterson; 1986). When women are beginning to take part in the affairs of the world, it is still a world that belongs to men (de Beauvoir; 1949).

De Beauvoir writes:

'people have tirelessly sought to prove that woman is superior, inferior, or equal to man. Some say that, having being created after Adam, she is evidently a secondary being; others say on the contrary that Adam was only a rough draft and that God succeeded in producing the human being in perfection when He created Eve. [...] If we are to gain

understanding, we must get out of these roots; we must discard the vague notions of superiority, inferiority, equality which have hitherto corrupted every discussion of the subject and start afresh' (Beauvoir; 1949).

Women want to be just like men, that is, men as they are today. They should not desire the same powers of men, but they should reject the ideas of power and hierarchy in order to achieve equality, affirms de Beauvoir. In practice, it implies

changing the society itself, changing the basic concepts of masculine and feminine models.

It is similar to the marxist proletarian revolution though led by women.

However, women fail to bring the change: Proletarians say 'We', Negroes say 'We', Women do not say 'We' in a authentic way. The proletarians have accomplished the revolution in Russia, the Negroes in Haiti; but woman's effort has never been anything more than a symbolic agitation. The reason for this is that women lack the concrete means for organising

themselves into a unit. (Beauvoir; 1949) (Jardine and Beauvoir; 1979).

Simone de Beauvoir's discourses led to public furore on the book's publication in France; the Pope also forbade Roman Catholics to read the book; François Muriac – a leading French novelist and right-wing commentator - led a public campaign to have it banned (Sellers and Plain; 2007).

On the other side, the public's reaction was immediate and de Beauvoir was caught amidst a succès de scandale (Dietz; 1992 : 77). Notwithstanding the evident criticism, de Beauvoir's phenomenological approach to understanding gender, combined with a recognition of her original syntheses of existentialism, Hegelianism, Marxism and anthropology in The Second Sex, has led to a major re-evaluation of her contribution to feminist thought (Tidd; 2008). Alternatively, de Beauvoir describes her book as something that 'will seem old, dated, after a while. But nonetheless...a book which will have made its contribution...'. (1949).

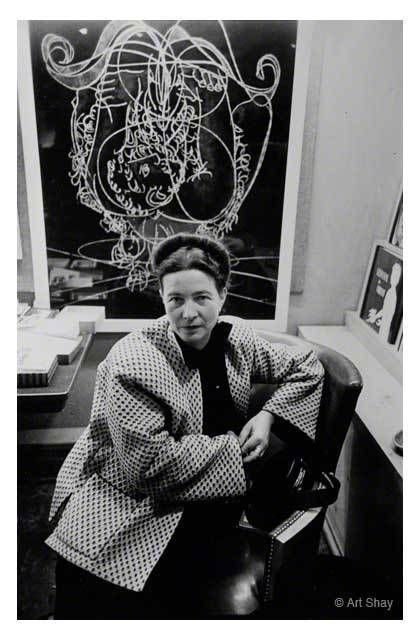

Image: ArtShay (no date). Simone de Beauvoir. Available from: http://zeigarnik.tumblr.com/post/33636441625/simone-de-beauvoir-art-shay

Bair, D. (1989). Introduction to the Vintage Edition. In: Beauvoir, S. de (1949). The Second Sex. H.M.

Parshley. New York: Knopf

Beauvoir, S. de (1949). The Second Sex. Great Britain: Penguin Books, 1972.

Dietz, M.G. (1992). Introduction: Debating Simone de Beauvoir. Chicago Journals. Autumn, 1992. Vol. 18, n. 1. Pp. 74 – 88. [online] Available from: University of Westminster.

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.westminster.ac.uk/stable/3174727 [Accessed 3 November 2015].

Fabijancic, U. (2001). Simone de Beauvoir's Le Deuxieme Sexe 1949-99: A reconsideration of

transcendence and immanence. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. Vol. 30, No. 4. Pp. 443-475. [online]

Available from: University of Westminster

http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxy.westminster.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1080/00497878.2001.9979390 [Accessed

4 November 2015].

Fallaize, E. (2007). Simone de Beauvoir and the demystification of woman. In: Plain, G.; Sellers, S. (2007). A

history of femminist literary criticism. Credo Reference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [online]

Available from: University of Westminster

he_demystification_of_woman/0> [Accessed 7 November 2015]

Gorrara, C.; Langford, R. (2003). France since the Revolution, texts and contexts. 1969-. London: Arnold.

James, C. A. (1997). Feminism and masculinity: reconceptualizing the dichonomy of reason and emotion. The

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. Vol. 17, No. 1⁄2. Pp. 129 - 152. [online] Available from:

University of Westminster

http://search.proquest.com/docview/203674973?OpenUrlRefId=info:xri/sid:primo&accountid=14987

[Accessed 4 November 2015]

Heinäma, S. (1999). Simone de Beauvoir's Phenomenology of Sexual Difference. Hypatia. Project Muse.

Vol.14, No. 4. Pp. 114 – 132. [online] Available from: University of Westminster

http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/hypatia/v014/14.4heinamaa.html [Accessed

4 November 2015].

Jardine, A.; Beauvoir, S. de (1979). Interview with Simone de Beauvoir. Chicago Journals. Vol. 5, No. 2.

Winter 1979. Pp.224- 236. [online] Available from: University of Westminster

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.westminster.ac.uk/stable/3173558?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 3

November 2015].

Mangus, A. R. (1953). The Second Sex by H.M. Parshley. Jstor. National Council on Family Relations. Vol.15,

pathway> [Accessed on 7 November 2015].

McCall, D. K. (1979). Simone de Beauvoir, ' The Second Sex ', and Jean-Paul Sartre. Chicago Journals. Winter,

<http://search.credoreference.com.ezproxy.westminster.ac.uk/content/entry/cuphflc/simone_de_beauvoir_and_t

No. 3. Pp 276 – 277. [online] Available from: University of Westminster <http://about.jstor.org/content/invalid-

- Vol. 5, No. 2. Pp. 209 – 223. [online] Available from: University of Westminster

http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.westminster.ac.uk/stable/3173557?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 1

November 2015].

Patterson, A.Y. (1986). Simone de Beauvoir and the Demystification of Motherhood. In: Wenzel, H. V. (1986).

Simone de Beauvoir: Witness to a Century. No. 72. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Scholz, S. J. (2008). The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir. Issue: 69; September/ October 2008. Philosophy

Now.[online] Available from: University of Westminster

https://philosophynow.org/issues/69/The_Second_Sex [Accessed 2 November 2015].

Tidd, U. (2008). Simone de Beauvoir Studies. Oxford Journals. Vol. 62, No. 2. Pp. 200 – 208. [online].

Available from: University of Westminster

http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/hypatia/v014/14.4heinamaa.html [Accessed

7 November 2015].