For anyone who has lived in Northern Arizona the effects of the wind on the environment can be very evident. Despite the title, I am not talking about digestive distress (although certain fermented foods that encourage gut flora can be Healthy and good for personal resilience!). The kind of wind that I want to talk about today is the wind that can dry out the soil, stunt growth of plants, and sap energy from animals/structures. Like sunlight, wind is a natural force that permaculture design takes into account in order to harness, direct, or deflect.

- It is not hard to guess what direction the prevailing wind comes from!

- bare soil unprotected from the wind is a recipe for making soil-jerky.

We have several basic things that are important to keep in mind when designing windbreaks or shelterbelts out of rows of trees and shrubs:

Wind direction, seasonality, and classification. Which direction does the wind come from in different seasons? It may be important to block a house from cold-dry wind in the winter but we may want to harness a light summer breeze. Do these winds come from different directions? It can be helpful to consult various articles about the types of wind and thermal gradients (Wikipedia)

Orientation and length. We should build our windbreaks perpendicular to the direction of the wind we are trying to block and ensure that the length of the shelterbelt is 20% longer than the area we are trying to protect. This is because strong winds will sometimes divert around the edges of a shelterbelt much like an airfoil on an aircraft, increasing the speed on the far side:

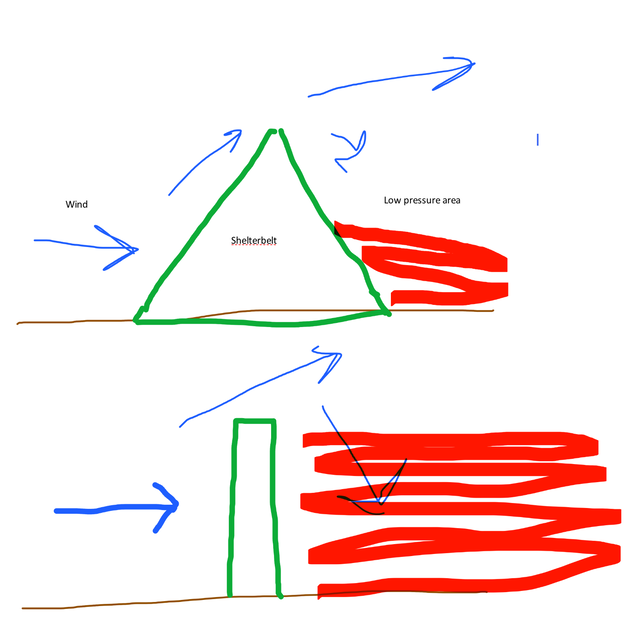

Height, density, and distance. The height of the windbreak will increase the size of the protected area downwind, but this also has an interaction with the density of the windbreak. Density is the thickness of the vegetation of the windbreak and this may be variable depending on if trees are evergreen or deciduous. Too little density will not slow the wind very much while too much density will cause such a strong low pressure area downwind of the shelterbelt that air is violently "sucked" back to the ground (causing destructive turbulent gusts).

Shape. The best shape for a windbreak causes a gradual lifting of the air. Imagine that you are viewing a windbreak from the side:

A shape of a triangle will decrease the size and intensity of the low pressure area downwind of the shelterbelt. This also decreases the intensity of winds that are "sucked down" to the ground. We can achieve this triangle shape by using a mix of tall trees in the middle, medium trees on either side (both up and downwind), and shrubs on the outside.

There are many other factors worth considering such as species selection and planting pattern. I would recommend doing what you can to stack functions by planting trees and shrubs that produce a yield, are adaptable to your environment, are aesthetically pleasing, and easy to maintain. A shelterbelt can be a source of food, firewood, habitat, and herbs for generations to come! While they may take a while to establish due to the slow growing nature of most trees, windbreaks and shelterbelts are an investment that will pay dividends for decades if properly designed.

I hope everyone can enjoy sustainably breaking wind! :)

-stay resilient!

-Scott