The Higgs boson appeared again at the world's largest atom smasher — this time, alongside a top quark and an antitop quark, the heaviest known fundamental particles. And this new discovery could help scientists better understand why fundamental particles have the mass they do.

When scientists at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) first confirmed the Higgs' existence back in 2013, it was a big deal. As Live Science reported at the time, the discovery filled in the last missing piece of the Standard Model of physics, which explains the behavior of tiny subatomic particles. It also confirmed physicists' basic assumptions about how the universe works. But simply finding the Higgs didn't answer every question scientists have about how the Higgs behaves. This new observation starts to fill in the gaps.

As the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), the scientific organization that operates the LHC, explained in a statement, one of the most significant mysteries in particle physics is the major mass differences between fermions, the particles that make up matter. An electron, for example, is a bit less than one three-millionth the mass of a top quark. Researchers believe that the Higgs boson, with its role (as Live Science previously explained) in giving rise to mass in the universe, could be the key to that mystery.

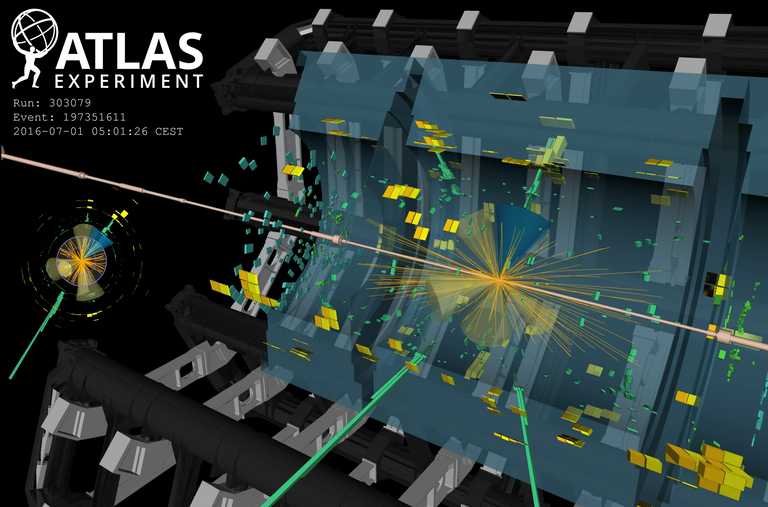

Two experiments — the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) and A Toroidal LHC Apparatus (ATLAS) — observed a decay that revealed that the Higgs 'couples' extremely strongly with the superheavy top quark, suggesting a close affinity between the particles. That result lines up with what physicists had predicted.

The new measurements 'give a strong indication that the Higgs boson has a key role in the large value of the top quark's mass. While this is certainly a key feature of the Standard Model, this is the first time it has been verified experimentally with overwhelming significance,' Karl Jakobs, a spokesperson for the LHC's ATLAS collaboration, said in the statement.

The new results were published today (June 4) in the journal Physical Review Letters. They don't represent a single observation but rather the faint signals of many observations, collected until the researchers had enough data to be certain of what they were witnessing.

The Higgs-top quark decay, called the 'ttH signal,' was published in the paper with a statistical significance measured at 5.2 sigma, meaning it had a far better than 1-in-3.5-million chance of being just a fluke in the data. A follow-up paper posted at the same time on the preprint server arXiv reports an even better significance of 6.3 sigma, which substantially exceeds 1-in-500-million odds of being just a fluke.

Congratulations @rusikgadov! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Congratulations @rusikgadov! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!