The ability to detect Earth's magnetic field has been confirmed in birds, insects and some mammals, which they use to migrate and orient themselves with the world around them, and now geophysicist Joe Kirschvink of the California Institute of Technology says he has identified in humans for the first time.

Best of all, Kirschvink states that their results can be repeated and verified - something previous experiments hinting at our magnetic sense - or magnetoreception - have not done.

"My talk went very well," Eric Kirschvink told Science magazine after presenting his results in April 2016 at the Royal Institute of Navigation in the UK. "We hit the spot. Humans can act as magnetoreceptors. "

To be clear, Kirschvink has so far presented only the results of a small essay with 24 participants, and he is still in the process of preparing the Paper, so this has not yet been revised.

Kirschvink received funding of $ 900,000 in funds, which he used to work with laboratories in Japan and New Zealand where he was able to personally confirm his theories. While the existence of "human magnetoreception" has been discredited before, experts think that this could be a real business.

According to a chemist at Oxford University, "Kirschvink is a very intelligent man and a very careful experimenter," said Peter Hore - a leader in the field of magnetoreception who did not participate in this research - told Science Mag. I would not have spoken of this in [the meeting] if I were not quite convinced that he was right. And the same can not be said of all scientists in this area. "

So how would humans be able to detect a magnetic field that we can not see with our own eyes? Now we know that not only birds and butterflies use this ability, mammals like dogs also use Earth's magnetic field, and mice, rats and tops build their nests along the lines of the magnetic field. However, there are conflicting views on exactly how they do this.

There are two main hypotheses to explain the underlying biological process of magnetoreception: one field thinks that Earth's magnetic fields could trigger quantum reactions in proteins called cryptochromes. These proteins have been found in the retina of birds, dogs, and even humans, but the way they feed magnetic information to the brain is not really known.

Another hypothesis suggests that there are actually receptor cells in the body that contain "tiny compass needles" made of a magnetic iron ore known as magnetite, which are oriented according to Earth's magnetic fields. Magnetite has been found inside the cells of bird beaks and trout noses, but, again, there is insufficient evidence to fully explain this ability.

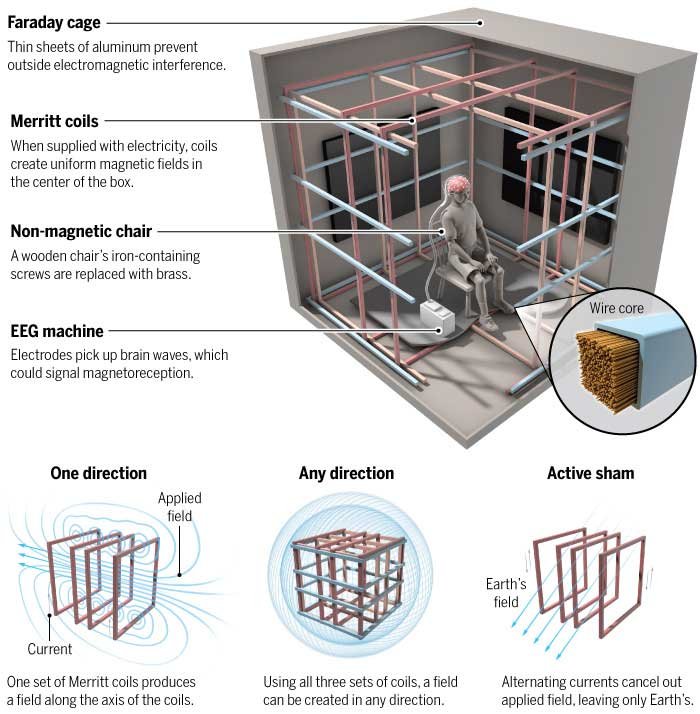

Kirschvink relies more on this second hypothesis, but his real interest is not in figuring out what is going on, but in showing first that agnetoreception is actually happening in humans. The problem with previous experiments is which have been unable to be replicated - think it is the result of electromagnetic interference when playing with the results. To eliminate that variable, Kirschvink has built what is known as a Faraday cage - a thin, aluminum housing that can detect electromagnetic background noise using wire rods. Inside the cage, people sit, and are only exposed to a pure magnetic field without interference, and no other stimulus.

Faraday cage, used in experiments to prevent the earth's magnetic field from interfering.

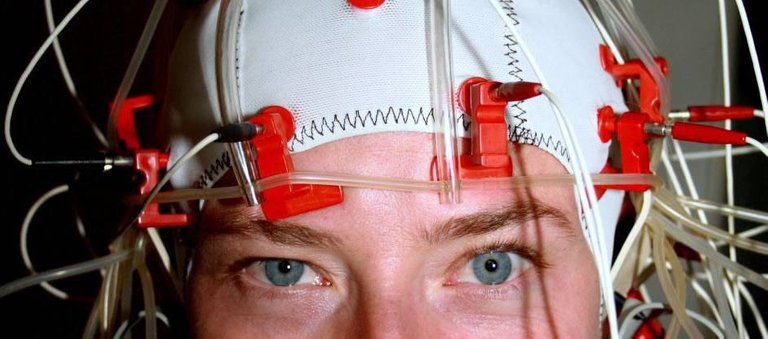

Kirschvink connects participants to EEG (electroencephalography) monitors to monitor brain activity, and then applies a rotating magnetic field, similar in strength to that of the Earth, to see if the brain shows signs of picking up any changes.

Kirschvink has been able to demonstrate that when the magnetic field is rotating to the left, there is a drop in the alpha waves of the participants.

"Suppression of alpha waves in the EEG world is associated with brain processing: a set of neurons were firing in response to the magnetic field, the only changing variable," he reports to Science Mag.

There is much more work to be done - a team in Japan is replicating the experiments, and a New Zealand laboratory is starting its own study following the same protocol. The results below should be examined by other researchers in the field and published in a peer-reviewed journal before we can assume magnetoreception in humans.

We have a long way to go, but it seems we could be closer than ever to show that humans have not completely lost touch with our sixth sense. And that's very exciting. "It's part of our evolutionary history," says Kirschvink. "Magnetoreception can be the primary meaning."

Sincerly,