Muslim academic Sapri Sale, who studied Arabic at the Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt, wanted to establish a better understanding between Indonesians and Israelis by teaching Hebrew to Bahasa-speaking students.

Indonesia and Israel do not have formal diplomatic ties. In fact, Israel is often portrayed negatively in Indonesian media because of its policies towards Palestine. En route to his historic state visit to Australia in 2017, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was forced to avoid the Indonesian airspace. Could something as simple as a language be the key to discovering commonalities?

Global Voices talked to Sapri Sale about how he came to learn Hebrew while studying Arabic, his inspiration for teaching Hebrew in Indonesia, and the struggles he faced in writing and publishing the first Indonesian-Hebrew dictionary.

Sapri Sale among his students in Jakarta. Photo courtesy of Sapri Sale, used with permission.

Global Voices (GV): How and why did you come to learn Hebrew in the first place?

Sapri Sale (SS): I want the world to know that not all Indonesians are (Muslim) militants. Our country is diverse. To me, Hebrew culture and language are no different to Arabic ones, and if Arabic can exist (in Indonesia) among Indonesian local languages and culture, then Hebrew has an equal right to exist in the country as well.

In 1989, I was an Arabic Literature student at Al Azhar University of Cairo. I was very much interested in Middle Eastern geopolitics; however, I became aware that in Egypt, Israel was portrayed negatively. At the time, the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt was already going on for about a decade. Yet, the media fuel anti-semitism sentiments among the general population. I refused to concur with hate and decided that to truly understand what was happening, I needed to learn Hebrew to know what Israel is all about without prejudice.

Ironically, despite the Egypt-Israel diplomatic relationship, trying to get my hands on Hebrew language books was not easy. Mind you, my sojourn took place during the pre-Internet era; I had no clue if there was an Israeli cultural center, and asking the Israeli Embassy was too daunting. With a bit of luck, I found some Hebrew books and started learning autodidactically.

After learning Hebrew for several years, I discovered an Israeli center in Cairo, and began to attend classes there in 1993. An Egyptian called Amer tutored me. Understandably, in the beginning, my presence was seen as odd, suspicious even, by the Israeli communities at the center: I look Asian and furthermore, I was a student at Al Azhar. There were 600 Indonesian students in Cairo, and I was the only one who developed an interest in Hebrew language and culture.

In 1996, I moved to Lebanon to pursue my career. Unfortunately, I had to stop learning Hebrew altogether, due to political reasons. In 1999, I found a new job with the Permanent Mission in New York. Over there, I'm free to rekindle my passion for learning Hebrew, and began to draft the Indonesian-Hebrew bilingual dictionary in 2006, after two decades of learning Hebrew.

GV: Tell us about the dictionary. What have been some of the challenges in having your hard work printed?

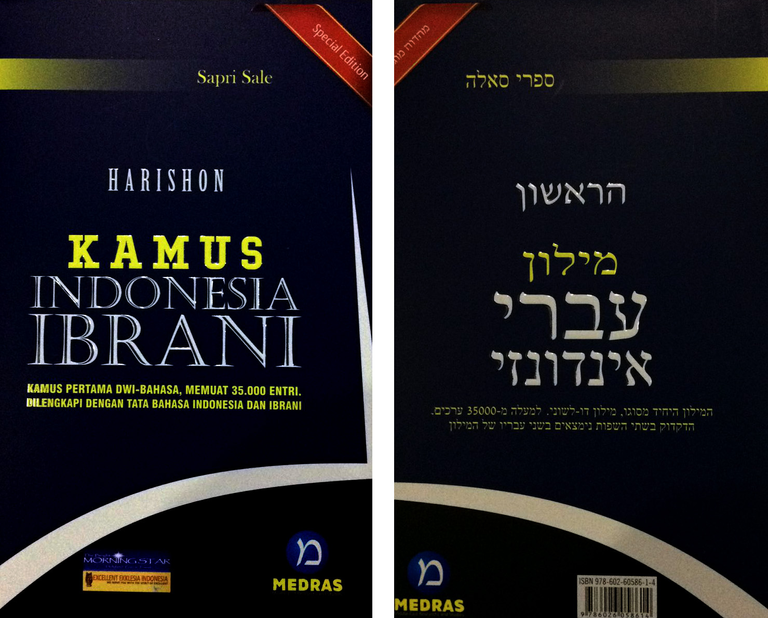

SS: It's a 450-page bilingual dictionary of modern Hebrew and Indonesian. It's a reference for Indonesians who want to learn Hebrew and for Hebrew speakers who want to learn Indonesian. This is the answer to my calling to bridge Indonesia and Israel, linguistically and culturally.

There were many challenges, as you can imagine. The Indonesian and Hebrew languages are worlds apart. I often stumbled in finding word pairings. This is where my Arabic knowledge came in handy, as Arabic and Hebrew are similar. Arabic became my reference in translating Hebrew words into Indonesian.

In 2016, once I finished writing, I had to deal with rejections. Popular publishers aren't so keen on anything Israeli, so naturally, my dictionary was dismissed as irrelevant, unmarketable, and politically incorrect. One day, I discovered an indie publisher in Yogyakarta, who was willing to do the job, once I personally funded the print run. But I encountered another roadblock while registering the ISBN. Normally, ISBNs are assigned in less than a month; I had to wait three months to obtain the ISBN for my dictionary.

GV: Israel remains a sensitive topic. Have you experienced any uncomfortable situations as a Muslim Hebrew teacher and author?

SS: I don't care about being mocked or bullied. Due to my choices and my work, cynics have nicknamed me ‘Sapri the Jew’. My extended family has shunned me, my former Al Azhar classmates have shunned me. My wife, who has followed every dictionary draft since day one, kindly reminded me that it's a waste of time. But I'm in top deep: 25 years of learning and practicing — it's too late to stop now.

I'm also being called a fraud; that my works are phony. To the naysayers, I'll just speak matter-of-factly — that my work is, as a Hebrew saying goes, ‘Not by might and not by power, but by spirit.’

I told my family that what I'm doing might have uncertain consequences, but it's something that needs to be done.

GV: If we were to attend your Hebrew class, what could we expect?

SS: About 70% of my students are Christians and 30% are Muslims. Many of my Christian students — academics mostly — wish to understand the Bible better. I expect that in the future, there will be more students from Pesantren (Koranic schools). Those from Pesantrens have an upper hand because they already know how to read Arabic texts, so learning Hebrew will be easier for them. My classes are held at the Indonesian Conference on Religion and Peace (ICRP), the only organization that's willing to take me in. Each class is one and a half hours long. I developed a learning method for my fellow Indonesians, so that after eight meetings they can read modern Hebrew, and after that they can learn autodidactically.

GV: Any future projects?

SS: Well, book writing mostly. My modern Hebrew grammar book is on the way and will be ready for printing soon. I also plan to publish another book: conversational Hebrew for Indonesian speakers.

The modern Hebrew-Indonesian dictionary is available by ordering directly from the author.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://globalvoices.org/2018/03/27/a-muslim-scholar-seeks-to-link-israel-and-indonesia-through-the-hebrew-language/