Researchers in London have developed scanning techniques that show what is written on the papyrus that mummy cases are made from.

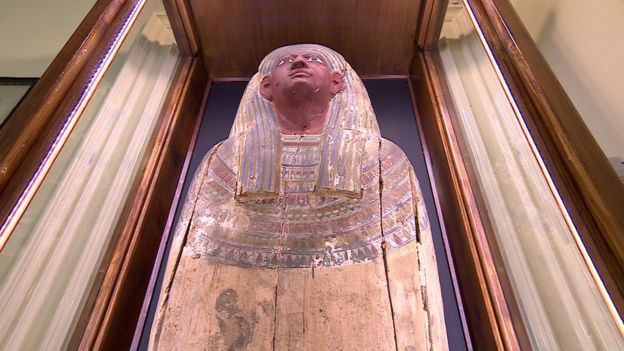

These are the decorated boxes into which the wrapped body of the deceased was placed before it was put in a tomb.

They are made from scraps of papyrus which were used by ancient Egyptians for shopping lists or tax returns.

The technology is giving historians a new insight into everyday life in ancient Egypt.

The hieroglyphics found on the walls of the tombs of the Pharaohs show how the rich and powerful wanted to be portrayed. It was the propaganda of its time.

The new technique gives Egyptologists access to the real story of Ancient Egypt, according to Prof Adam Gibson of University College London, who led the project.

"Because the waste papyrus was used to make prestige objects, they have been preserved for 2,000 years," he said.

"And so these masks constitute one of the best libraries we have of waste papyrus that would otherwise have been thrown away so it includes information about these individual people about their everyday lives"

The scraps of papyrus are more than 2,000 years old. The writing on them is often obscured by the paste and plaster that holds the mummy cases together. But researchers can see what is underneath by scanning them with different kinds of light which makes the inks glow.

One of the first successes of the new technique was on a mummy case kept at a museum at Chiddingstone castle in Kent. The researchers discovered writing on the footplate that was not visible to the naked eye.

The scan revealed a name - "Irethorru" - a common name in Egypt, the David or Stephen of its time, which meant: "the eye of Horus is against my enemies".

Until now, the only way to see what was written on them was to destroy these precious objects - leaving Egyptologists with a dilemma. Do they destroy them? Or do they leave them untouched, leaving the stories within them untold?

Now, researchers have developed a scanning technique that leaves the cases intact but allows historians to read what is on the papyrus. According to Dr Kathryn Piquette, of University College London, Egyptologists such as her now have the best of both worlds.

"I'm really horrified when we see these precious objects being destroyed to get to the text. It's a crime. They are finite resources and we now have a technology to both preserve those beautiful objects and also look inside them to understand the way Egyptians lived through their documentary evidence - and the things they wrote down and the things that were important to them."

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-42357259