“Under the relentless grip of unyielding stress or the looming specter of fear, the frontal cortex of an individual undergoes a disconnection, impeding their capacity for foresight and sound judgment. This incapacitation paves the way for the ascent of authoritarian inclinations, wherein the prey succumbs to the dominance of external forces.”

Within the intricate fabric of human existence, a biological phenomenon connects us to our primal forebears, albeit expressing itself in ways significantly divergent from the survival challenges they confronted. It is the concept of homeostasis, a term likely etched into the recesses of your memory from ninth-grade biology. Homeostasis, the delicate equilibrium of an organism's internal environment, where ideal conditions for various physiological parameters are maintained.

Picture a zebra in the African savannah or a half-starved lion on the prowl, each grappling with the imminent threat of a physical crisis. The stress response in these creatures is a swift, instinctive cascade of hormones—adrenaline and its companions—aimed at restoring homeostatic balance. It's a matter of life and death, a survival strategy honed over millennia.

However, as cognitive, socially sophisticated beings, we, the humans, have co-opted this ancient stress response mechanism for a myriad of psychological reasons. No longer bound by the immediacy of a predator's pursuit, we find ourselves triggering the stress response not just in the face of tangible threats but also in anticipation of imagined challenges.

Consider the financial landscape, where the mere mention of terms like the prime lending rate can induce stress in individuals. Unlike the zebra's fleeting encounter with terror, we subject ourselves to prolonged stressors—30-year mortgages and the complexities of modern life. It's a perplexing evolution of a system designed for survival in the wild.

The crux of the matter lies in the divergence between the evolutionary purpose of stress and its contemporary applications. Our minds, with their intricate web of memories, emotions, and thoughts, activate the same stress response that once served our ancestors in life-or-death situations. We, however, engage this physiological mechanism for protracted periods, imposing a wear and tear on our biological systems.

In this modern era, stress is not just a reaction to imminent danger; it is a constant companion, spurred by societal expectations, economic pressures, and the relentless pace of technological advancement. We grapple with the paradox of triggering a response evolved for fleeting moments of peril in the face of chronic, often self-imposed, stressors.

The implications of this cognitive dissonance are profound, leading to a spectrum of human experiences from anticipation and anxiety to full-blown neuroses. The very sophistication that sets us apart as a species becomes a double-edged sword, as our minds navigate a world far removed from the ancestral plains.

In navigating the intricacies of stress, we find ourselves at the intersection of biology and psychology, confronting the consequences of our evolved minds contending with the challenges of a rapidly evolving world. As we unravel the complexities of stress in the human condition, it becomes imperative to understand the delicate balance between our primal instincts and the intricate tapestry of modern existence.

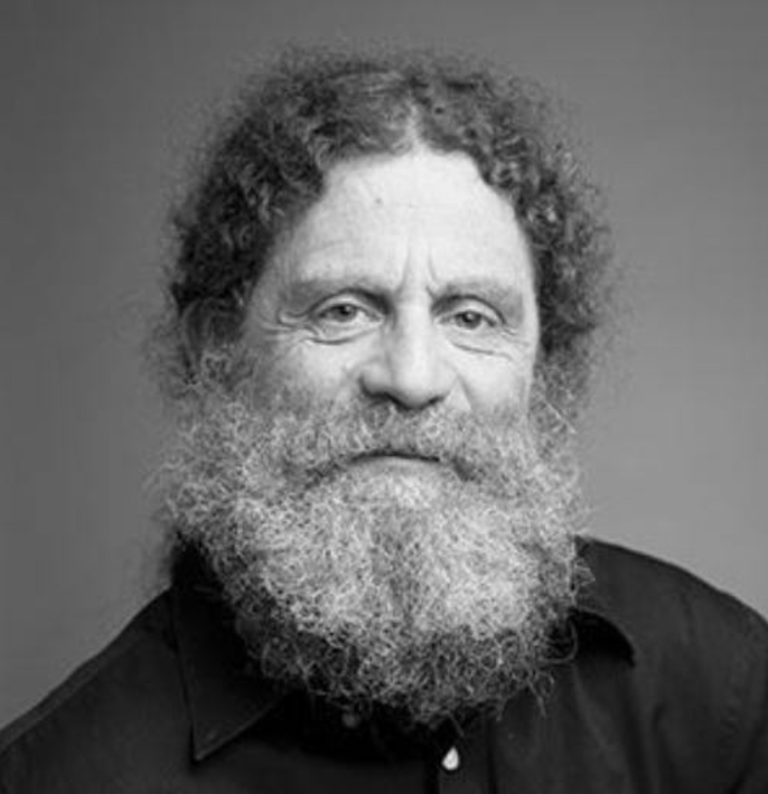

Robert Sapolsky: The Psychology of Stress

Robert M. Sapolsky, Ph.D., is the John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Professor of Biological Sciences and a professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford University. In this clip from his talk for the Science of a Meaningful Life series, Sapolsky explains why the stress response, which evolved for short-term physical crises, can become a long-term, chronic problem for human beings.

Source: The Psychology of Stress