Well, a semester is complete, and as you can hopefully tell from my pixelated image above, we are all pretty damn relieved. If anyone can recall, I had planned on continuously blogging about medical school here on Steemit to give potential doctors of the future a look at what colleges of osteopathic medicine are like.

The fact that I've managed maybe two posts all semester tells you a lot about medical school. It's as all-encompassing of an endeavor as I've ever been part of. Whatever windows of free time that I had outside of the lectures, anatomy labs, OMM (Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine) labs, doctoring practice, volunteering hours, they clearly weren't spent blogging. In medical school, free time is a luxury. For me at least, every waking hour not spent productively has been an hour spent that will optimize FUTURE productivity....mindfulness, exercise, SLEEP, letting yourself have a drink with the other students going through the same process as you...these were the activities that took precedent over free-writing.

I wish I could share with you the wild array of images that have been seared into my mind this semester, but, for obvious reasons, photos were not allowed in the most captivating of places in the medical school atmosphere--the anatomy lab. I will try my best to recount a couple of the most interesting/oddest experiences.

In the anatomy lab, in a school of 140 students and about 24 cadavers, there were about 6 students per cadaver. Upon first encounter, the cadavers were completely covered, without a view of the more distinctly human characteristics of the body: the head, hands, or feet. My lab group was given a female, who had died of old age in her 90s. The details of her life and her identity were not disclosed to us. We just knew that the life-force; the consciousness that had previously occupied the body laying in front of us and all the other bodies laying on the cold metal of the anatomy lab, had probably pondered the pros and cons of donating their body for the sake of human health and decided that yes, they would allow inexperienced, green, sometimes immature 1st year medical students, mostly in their early to mid 20s, and the occasional faculty member to carve, yank, pull, and dig into every region of their bodies with scalpels, scissors, probes, tweezers, and their own fingers. The access permitted had few limitations. Throughout the semester, everything from the spinal cord, to the tiny ear bones called the ossicles, to the eyes, to the genitals, to the brain, to the bowels, to the spleen, lungs, and heart were all part of the curriculum. The medical students, like famished termites at a carpenter's workbench, did not tend to hold back. As we progressed through the semester, we slowly uncovered our cadaver's parts that made her seem more relatable--more than just a sac of flesh, bones and muscle. The uncovering of her eyes and hair, her belly button, her long fingernails (which continue growing after death); these unveilings were all miniature shocks to the system, reminding me of life that once permeated the being and of everyone's destiny to meet similar fate.

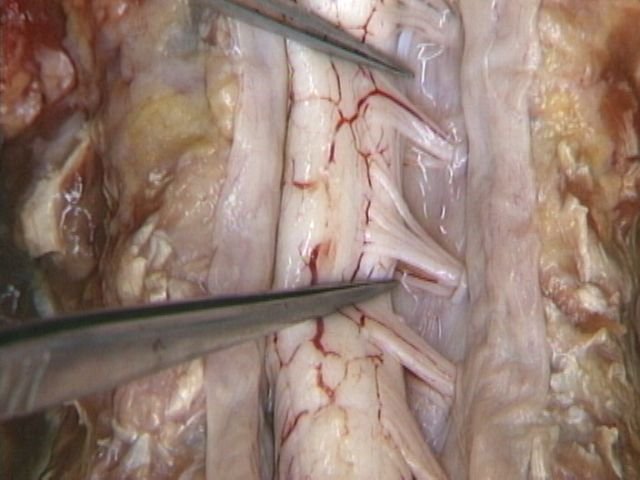

One of my most interesting experiences in the lab was discovering and doing a presentation on the spinal cord. In order to gain access to the cord, with the back skin pealed and tissues cleaned, we used a mallet and chisel to break through the posterior part of the vertebral column called the lamina. Once the lamina was broken through on both sides, we removed the spinous processes (the portion of our vertebra that we can feel protruding from our backs underneath our skin). Removing the spinous processes, and teasing through a few layers that line our central nervous system (the dura, arachnoid, and pia mater) led to the view of the spinal cord, the bundle of nerves that runs from our brainstem down the hole in our skull called the Foramen Magnum. The cord then passes through the central gaps in our vertebrae, while diverging into branches along the way as it supplies our body with so many of its capabilities, and it eventually ends near as it approaches the tail bone. It was a moment of wonderment for me to visualize the spinal cord: this squishy, compressed, thin, squid-like cord that provides us with sensation, our ability to move and carry out all of the functions we don't have to deliberately carry out (like passing food through out intestines). This below is what our spinal cords look like. When I see humans walking around now, I often picture this blob of nerves doing its fair share of the work.

Seeing this had a way of wiping the superficial bullshit of life out of the way for a while. It may be a similar feeling to that of a car aficionado who looks under the hood and sees a beautiful, well-oiled machine leading to the pristine function of the automobile. As a people, humans devote a substantial amount of time and effort focused on and fine-tuning our external appearance. Why? Because it happens to be visible to everybody (we can't see through skin), and we happen to form a lot of our opinions and judgments based on external experience. But there's so much that goes on underneath the skin that most people never have a chance to see. It was mesmerizing to see in detail just how much we take for granted in life. It would probably take a lifetime just to understand ourselves as the complex machines that we are: how we respire, get rid of foreign invaders, bring blood, nerves, and lymphatics to every corner of the body, our digestion, our hormonal system, how are muscles of mastication allow for us to undertake the surprising and overwhelmingly intricate action of chewing. And for any of you interested in medicine, you might be happy to know that the process of looking at and dissecting human bodies can have the impact of making an anthropologist out of you.

I'll end this post with a ridiculous story. In the context of an anatomy lab, you never know what sample of people you're going to get. People have all kinds of medical issues. A couple cadavers had heart stents in place, our cadaver had undergone a hysterectomy, other cadavers had different types of joint replacements, giving us the ability to see just how well our society has learned to insert artificial parts into the human body. But one cadaver took the cake: a penis pump. Until that day, I had no idea how penis pumps worked...I had only seen the occasional reference in movies like American Pie. You may or may not be able to imagine just how outlandishly weird and once-in-a-lifetime it was to learn how these pumps work on a dead person. I won't fill you in on the details....The students were lining up at this cadaver's table, chastised by our anatomy professors for daring to let out a chuckle at the ludicrous nature of what we were looking at. One of my good friends at school, got up to take a glimpse, and couldn't help but let out a guffaw. Another student looked at him knowingly and said, "First timer, huh?". Just another day in anatomy lab.

Hopefully I'll have more stories for you soon because I'm trying to really savor my break and get some writing in,

Just curious, do they allow you to take pics of the cadavers?

They do not, you could get expelled for doing so!