I met them on a mountain road near Przhevalsk. Far below in the valley a cuckoo was calling monotonously, as in an old clock. The mountain ashes were covered with white blossoms, so like the blossoms of the European cherry. Despite the great height and proximity of snow, it was hot here. The air was heady from smell of sun-warmed grasses. It was shearing-time, and the flocks were coming down to the valleys. All the roads were blocked by sheep. Drovers on horseback would suddenly appear amidst clouds of dust, and the air would be filled With their shouting, the bleating of sheep and the barking of sheep dogs. If you looked up along a road you would see a big cloud of dust in one spot, then another and another. The flocks were hurrying down to the valley.

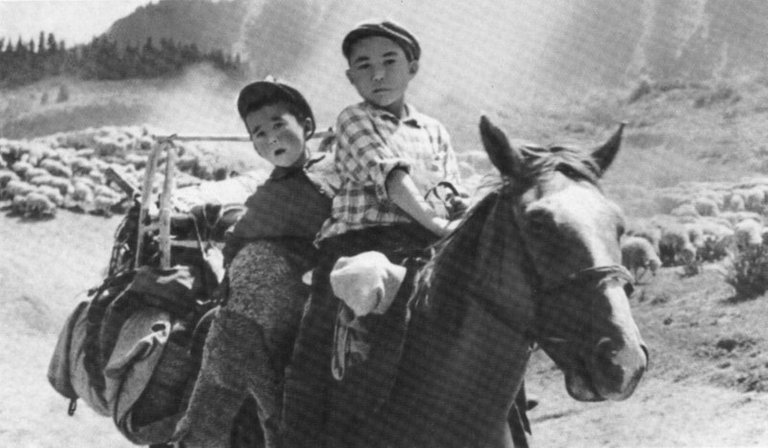

I came upon two boys at the head of one flock. They were riding a brown mare, with a sick lamb lying across the saddle. There was so much lashed on behind them that I could not help asking what they were carrying. Their baggage consisted of a tent, a child's cradle, a vessel of fermented mare's milk, a black kettle, a shotgun, a pail, a kerosene lamp, a rolled felt pad and a portable stove. All this had been skillfully packed and now swayed in motion with the mare's steps and the two riders. A second horse was tied to the baggage with a length of rope. For some reason or other it carried no pack. It would snatch a mouthful of grass now and then, drawing the rope tight, and then the younger of the two riders would turn back angrily.

The two brothers, Keken and Bolot Tokrashov, their mother and father were all coming down to the valley from the mountain pastures. The flock they were bringing in numbered about a thousand head. Their father was rounding up the strays. Their mother was also on horseback. She carried her infant daughter in a red blanket. Keken and Bolot, her two elder sons, were in charge of the family's possessions. They had all lived in a tent in the mountains since the spring. Now they were heading back to the village of Teploklyuchenki. They had covered twenty-five kilometers that day. Anyone who has gone up into the mountains on horseback and knows what the rocky climbs, descents and shallow but turbulent streams are like will understand why I changed my plans to accompany the boys for a while. I was captivated by them. The elder was nine, the younger seven. They were astounded to see a man in the mountains with several cameras slung over his shoulders.

"Are you a spy?" Bolot, the younger boy, asked naively.

I smiled and said I was from Moscow.

"Oh, he's probably from a TV studio," the elder replied.

They both said they missed watching television in the mountains.

"We'll stay up all night, now."

"That's if Grandma and our other sister didn't break the set," Keken added.

I kept snapping pictures and could only marvel at their composure. They weren't showing off in the least, and their replies were brief and to the point. It was as if I were speaking to adults. Bolot had one arm around the sick lamb. He kept urging the second horse on, while Keken led the flock and kept up a civil conversation.

I asked him whether, he knew the poem "One day in the winter the cold was consuming . . ."

"You mean about the boy and the horse? Yes, our teacher read it to us."

"There's a book about an old man and a horse. The horse's name is Gulsary."

Keken had not read the book, but when I told them who the author was they both said they knew Chinghiz Aitmatov.

"He was on TV."

We covered five kilometers as we talked. Their father drove the flock, their mother rode along, cradling her daughter, while the two brothers led the way on their intelligent, gentle horse. I took about a hundred pictures of them, trying to get the breath-taking turns of the mountain road in the background, but finally chose the very first shot, the one I took as Bolot was saying: "Are you a spy?"