This man right here told me he could kill me with his mind...

This man right here told me he could kill me with his mind...

For twenty-four years, the U.S. government had a spy program that involved psychics.

And not just ordinary psychics, but often military veterans who were trained by the government to become psychics.

Fascinated by this, I decided to pitch my editors on a story on this fascinating chapter in American history:

Remote viewing.

The resulting article, one of the pieces I worked the hardest on, was killed and never published.

Why?

“It kind of sounds like you believe this,” my editor said.

“All I’m doing is reporting on what factually happened,” I replied.

One of my few regrets in my career is that this piece was never published. Now, thanks to Steemit, it’s time.

So welcome to post number two in my “killed and cut” series.

Enjoy, let me know your thoughts, and let me know if you’d like a second article explaining how you can try to “remote view” yourself.

Welcome to….

PSYCHIC BOOT CAMP

By Neil Strauss

“For ten years, I had the opportunity to sit in a dark room with my eyes shut and work for the CIA,” said Russell Targ over lunch at the Texas Station Casino. “I was a psychic spy for the CIA, and I found God.”

Mr. Targ is, by all appearances, a stereotypical nerd genius, with pants pulled past his belly-button, moplike gray curls, thick black-framed glasses, and a high, pinched voice. In the 1950’s, he made his reputation by helping to develop the laser. But in 1972, his life took a turn for the surreal when he and another physicist at the Stanford Research Institute, Hal Puthoff, found themselves with a contract from the CIA. For the next two decades, with additional support at various times from the DIA, NASA, Air Force, and Army Intelligence, Mr. Targ and Dr. Puthoff were at the forefront of one of the strangest chapters of the Cold War: psychic espionage. Teams of agents were trained and tasked at Stanford in a type of ESP known as remote viewing, in which, with pen, paper, and brain, they tuned into events taking place in locations and times outside ordinary sensory perception.

For a quarter century of American history, they performed such top-secret tasks as mentally penetrating Russian nuclear laboratories, checking on hostages in the American embassy in Tehran, and scouring the globe for secret terrorist camps. When asked after his presidency what had been the most unusual event of his term, Jimmy Carter said that it was when a psychic in the program found the location of a downed Russian spy plane in Zaire.

As he discussed the Congressmen and chiefs of staff who witnessed and even performed amazing feats of remote-viewing, Mr. Targ suddenly turned to me and asked, “Have you ever done any types of psychic things?”

I told him that I wasn’t sure.

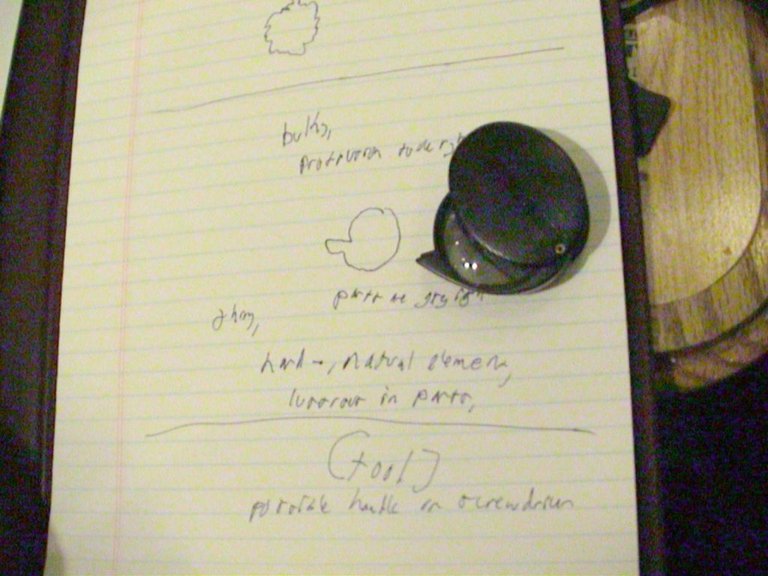

“I can try to show you something psychic,” he responded. With that, he pushed my salad aside and put a notepad and a pen in front of me. “I have an object in my pocket,” he went on. “It’s not an ordinary kind of thing that you would find in your pocket. And what I’m inviting you to do is try and describe the shapes that come to mind. But don’t try and guess my object.”

I hesitated and tried to change the subject, but to no avail. “If you were going to draw a shape associated with this object, what would you draw?”

I drew an uneven circle and then began to describe an image it suggested: “It’s lustrous in parts.”

“What else comes to view?” he asked. “Is there anything else interesting that you can tell me about it?”

I free-associated, telling him whatever came to mind. “Parts are gray or black. It’s shiny. And maybe it’s rough on the outside.”

“You can write all that down,” he continued. ”Now why don’t you draw some more. Let it come to you. You can look into your immediate future, because I’m about to lay this in front of you..”

I put the pen to the paper and let it go. It traced a circle, but at the bottom right, for some reason, I sketched a little boot-shaped protrusion. I looked at it and apologized, ready for him to pull a wallet or pencil out of his pocket.

“Now, tell me, without naming the object, what is the overriding property?” he asked.

“Well, I feel like there’s something poking out, like protruding to one side. And I still feel like it’s lustrous in parts.”

“Well,” he said, “that’s all entirely correct. Would you like to see the object?”

“Wait. There’s one more thing I want to write down. I know I’m not supposed to name it, but the protrusion feels like a handle or something you hold onto, so maybe it’s a tool. I don’t know. Maybe I’m going too far.”

“You can write that down if you want to,” Mr. Targ said as he pulled an object out of his pocket, placing it next to my sketch. It matched it perfectly—in size, shape, and description. It was a magnifying glass in a black, round, rough-surfaced case with a little protruding handle that could be used to pull the shiny magnifying lens out.

My actual drawing next to Targ's hidden object.

My jaw dropped open, as did those of two others at the table. Maybe it was psychic ability, maybe it was chance, maybe it was stage magic. Either way, Targ seemed nonplussed. “I have a background of 30 years in physics,” he said. “So I wouldn’t be doing something that didn’t actually work.”

I laughed nervously. “The secret,” he continued, “is that there isn’t really any secret. It’s an ability we all have.”

Something strange is happening across this country: Ever since the government declassified portions of its remote-viewing program a few years ago, the psychics it trained (many of them with no prior experience in the paranormal) have been running loose, teaching ordinary civilians how to be psychic.

Remote viewing, they say, is not an esoteric knowledge only attainable by a few special adepts and genetic freaks.

Anyone can do it. They just need to know how. Many compare remote viewing to playing guitar: with proper teaching, just about any human being with hands can learn to play a few songs. But only someone born with a natural talent and aptitude for the instrument can become a master musician like Paco de Lucia or Jimi Hendrix.

So, for fees ranging from several hundred to several thousand dollars, military-trained psychics (even a former general) have been teaching their hard-won skills. And these classes are not attracting wackos, new-agers, fringe-huggers, and conspiracy nuts. They’re attracting CEOs, stockbrokers, engineers, and others who don’t seem to have a woo-woo bone in their bodies.

“I’m not really into the paranormal,” said Victoria Bazeley, a 42-year-old executive at Disney Interactive in California who took a remote-viewing course with a former Army Sergeant named Lyn Buchanan. “The reason I got involved was because it was scientific and it had a military background. The fact that it was very cut and dry and could be measured appealed to me. It didn’t sound too easy, like a parlor trick.”

If energy was the new-age trope of the consciousness-expanding 70’s, then information is the meta-religion of today. There is no world view, no mystical belief system, and no magic involved in remote viewing. Its practitioners range from the devout to the atheist. The theory is that your mind is like the internet: all data concerning space and time is connected. All you have to do to log on is sit down with a pen and paper, trust your intuition enough to write down the bits of sensory data that appear in your mind, and then analyze that data.

The ranks of civilian remote-viewers include the author Michael Crichton, who helped with a psychic underwater treasure hunt, and Billy Dee Williams, the former Star Wars actor who now writes remote-viewing mystery novels. In a more unusual development, the wife of one Hollywood actor left her hubby to marry her remote-viewing teacher. In addition, remote-viewers have been hired for everything from corporate espionage to missing-children searches.

“We get a lot of flack from the psychic community because we’re destroying their monopoly,” Mr. Smith said. “People could embrace remote viewing like they embrace their TVs.”

Though that day may still be a distant dream, remote-viewing has at least been expanding out of normal paranormal circles. “When the information first came out,” said Mr. Buchanan, a gentle grey-bearded Texan who seems to share the pot belly common to most former military remote-viewers, “we got 8 to 20 applicants a day for classes. I turned down 95 percent of them—flaming kooks, really bad. Now I’d say that 95 percent of the people who call us are very level-headed people, a lot of whom want to use it in their businesses. They know that this isn’t magic or craziness. What we teach is the real thing. It’s not a toy. If someone has mental problems, you don’t teach them this stuff.”

Perhaps the best thing about remote-viewing, whether you believe in it or not, is that it has a message. To sit down in a room and somehow guess an object inside a pocket, draw a picture sealed in an envelope, see a land mass on the other side of the world, or mentally travel back in time is to experience first-hand the fact that we live in a non-local universe, in which everything is somehow connected. And out of that comes some very profound thoughts on mankind, the universe, and individual responsibility. In a time of increasingly bloody video games and misanthropic music, here is something that is not only far cooler than Doom and Eminem—real psychic ability for you and me—but comes with built-in morals and family values.

“Once you find out that you can do it, you go ‘Whoah! Now what do I do?’’” said Mel Riley, a taut-faced, well-tanned former Army viewer, recalling his initial training. “It changes your whole view of the universe. I can’t say much more than that.”

Mr. Targ explains the change as the discovery that “you’re not a physical body—you’re an awareness and there is no separation of consciousness.” The result, he continued, is that compassion is seen as a natural state, because we are all the same.

Several recent, non-military students, from a retired high school teacher in Chicago to a biotech-company executive on the West Coast, reported similar insights. “It’s given me a little bit more of a reserve against dying, “ said one student, David Hathcock, a retired CEO of a telecommunications company in Arizona. “Every time you do a successful viewing, your mind proves that it’s capable of not being in your body, because it can go to another place or time. If your mind can do that, there’s a part of you that’s not physical and must therefore be spiritual. It’s the first proof in my opinion that can be verified personally and on demand that we have a spiritual self.”

Bill Ray, a solidly built, weather-beaten former Army remote-viewer now working non-psychic counter-intelligence in Europe, still recalls his first experience, when he correctly identified a site that turned out to be Mr. Ranier. “You think, ‘I’m doing something that I know is impossible, and I can’t tell anyone about it,’” he said. “Every other impossible job they gave you in the Army was actually impossible.”

“I don’t think I missed more than two targets in a row,” he continued. “When we went to brief someone, we had a red book with some of the more spectacular work we’d done. There were about 106 cases. Of those, on 53 of them we had received the highest possible evaluation..” And, he added, an agency’s work receives such an evaluation not simply because the information is accurate, but also because it turns out to be useful and valuable.

Code-named at various points Gondola Wish, Grill Frame, Center Lane, Sun Streak, Project Scanate, and Star Gate, the remote-viewing program began with algae: In working with lasers and quantum electronics at Stanford University, Dr. Puthoff wondered if physics theory could handle concepts like consciousness. He wrote a proposal for experiments with algae to determine this, which somehow caught the attention of a flamboyant New York psychic named Ingo Swann, who called Dr. Puthoff and said that working with psychics instead of algae would be a better way to explore the gray area between physics and consciousness.

"On a lark,” the dry, low-key Dr. Puthoff said, he called Mr. Swann in to the lab. The physicist was surprised to discover that Mr. Swann was able to psychically draw a picture of a shielded magnetometer. As he did so, the levels of the magnetometer varied slightly. Dr. Puthoff wrote a report, and next thing he knew, two CIA agents were in his office. It seems that not only was there a missile gap between the United States and Russia, but, now that the CIA had learned of Russian ESP experiments, there was a psychic gap as well.

The most paranormal aspect of the program, according to Mr. Targ, who soon hired by Dr. Puthoff , was that it survived for 24 years in a world in which it’s rare to get a military contract awarded and even more difficult to get it renewed.

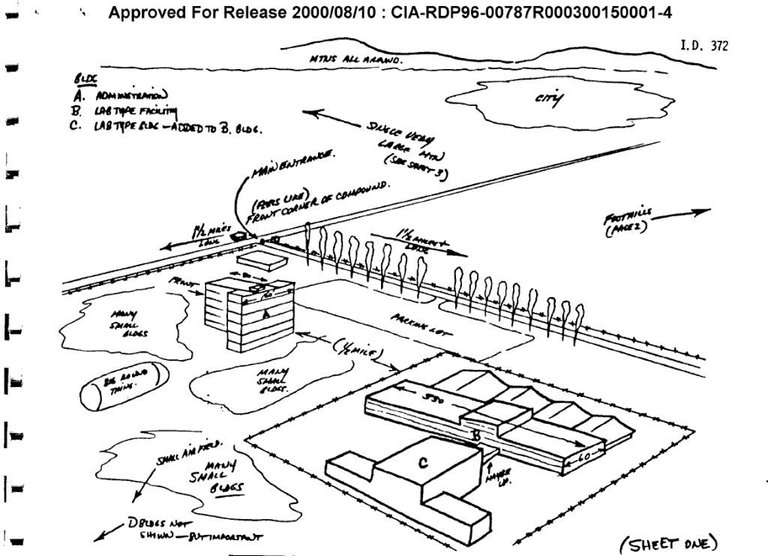

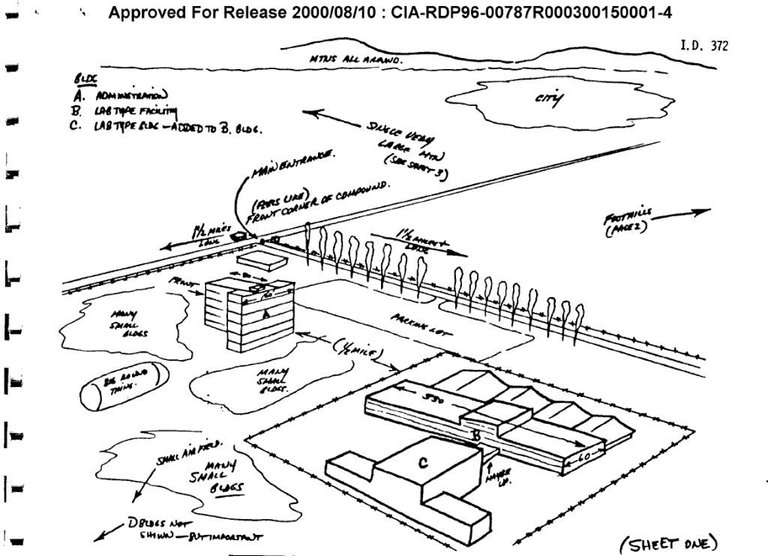

According to eyewitnesses and declassified CIA documents, their sessions with Mr. Swann and another psychic named Pat Price were powerfully accurate: secretaries typing out the transcripts of their sessions were afraid that they would be remote-viewed in the bathroom and the CIA, on receiving the project’s first set of results, launched a TK-year Pentagon investigation trying to figure out who had leaked such classified information to Mr. Swann and Mr. Price, who eventually left the lab to work directly for the CIA (where his operations remain classified).

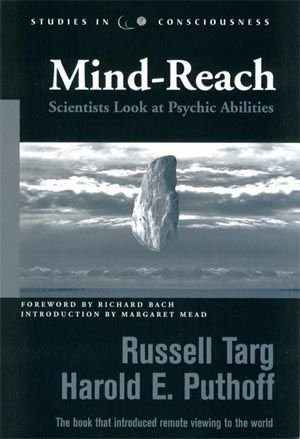

The remote-viewing program received its own East Coast branch in 1977 when an Army captain named Skip Atwater stumbled across a copy of a book by Mr. Targ and Dr. Puthoff, Mind Reach, and managed to convince his higher-ups that remote-viewing posed serious intelligence threats and possibilities.

“We bugged people’s phones, broke into their offices, and placed agents on their staff, so why not remote view them,” said Mr. Atwater, who published his memoirs last month, “Captain of My Ship, Master of My Soul.”

Mr. Atwater distributed personality tests around the Army until he put together a team of potential psychics, which operated out of Fort Meade in Maryland. The star of this unit was a Vietnam veteran named Joe McMoneagle.. A deep-voice, thick-necked military man, he drew detailed diagrams of Chinese nuclear weapons at Lop Nor, located bugs in American embassies, and discovered a massive state-of-the-art missile-carrying submarine the Soviets were building. When he retired from the Army, Mr. McMoneagle received a National Legion of Merit Award for being one of the “original planners and movers of a unique intelligence project that is revolutionizing the intelligence community” and thus “providing crucial and vital intelligence unavailable from any other source.”

Mr. McMoneagle now works at the Monroe Institute with Mr. Atwater, a campus where sounds are used to induce a state in which a subject’s mind is awake and their body is asleep, allowing them to achieve self-reflective insights, explore new states of consciousness, and sometimes even have out-of-body experiences. For years, agents in the remote-viewing program posed as civilians to attend the institute’s Gateway Voyager Program and learn how to better enter a meditative state conducive to remote viewing.

In person, Mr. McMoneagle has a tendency to utter, in the way that other men might say “I drank a beer today,” lines like, “I can make you wish you were dead at a distance.”

Like Mr. Targ, Mr. Smith, and others, he doesn’t think crystal-ball gazers and Tarot-card readers make good remote-viewers. Rather, more ordinary people do: those who are self-motivated, outgoing, tend to work alone, are successful at their jobs, and have an artistic bent excel. He added that people with experience in meditation tend to excel, as do those from abusive backgrounds since they have been using their intuition for so long. “They can read somebody’s face,” he said. “They know what’s going on behind the eyes. I’ve had to do that since I was small.”

Where some see remote-viewing as a newly evolving future consciousness, Mr. Moneagle, who still performs several thousand remote-viewings a year, sees it as a vestige of a distant past, an ancient survival skill we’ve evolved away from. He estimates that .5 percent of the population—or one in two hundred people—are world-class remote-viewers. “They may not know they are psychic, but they’re employing it,” he said. “They’re the ones running a business by the seat of their pants and making a lot of money, or making sixty five percent accurate predictions in the stock market and getting paid for their advice.”

To hear military men like Mr. Moneagle, Mr. Ray, and Mr. Atwater talk about it, remote-viewing seems as plain and everyday a phenomenon as sunshine. Unconvinced but confused by my experience with Mr. Targ, I played a tape recording and showed photos of the restaurant magnifying-glass session to Franz Harary, a stage magician regarded as the best in his field. Whenever confronted with the paranormal, he said that he always looks for a logical explanation. But after looking at the data, he said, “With the experience you just showed me, there is no way magic could be involved.”

Somewhat encouraged, I flew to Austin to take a five-day, $2000 remote-viewing training course with Mr. Smith (remote-viewing may come naturally, but it doesn’t come cheaply), who spent seven of his 20 years in the Army as a remote-viewerr. Mr. Smith probably never would have become a psychic spy if he hadn’t run over his cat in 1983. Immediately after the accident, he drew a picture of his cat chasing a butterfly, which still hangs in his home today. When two military neighbors, Mr. Atwater and another remote viewer stopped by his house, they saw the picture, looked at each other, and exclaimed, “Trackers!”

Trackers are a remote-viewing technique in which viewers make random dots on a piece of paper until their subconscious takes over and starts automatic drawing, hopefully providing some information about the target.

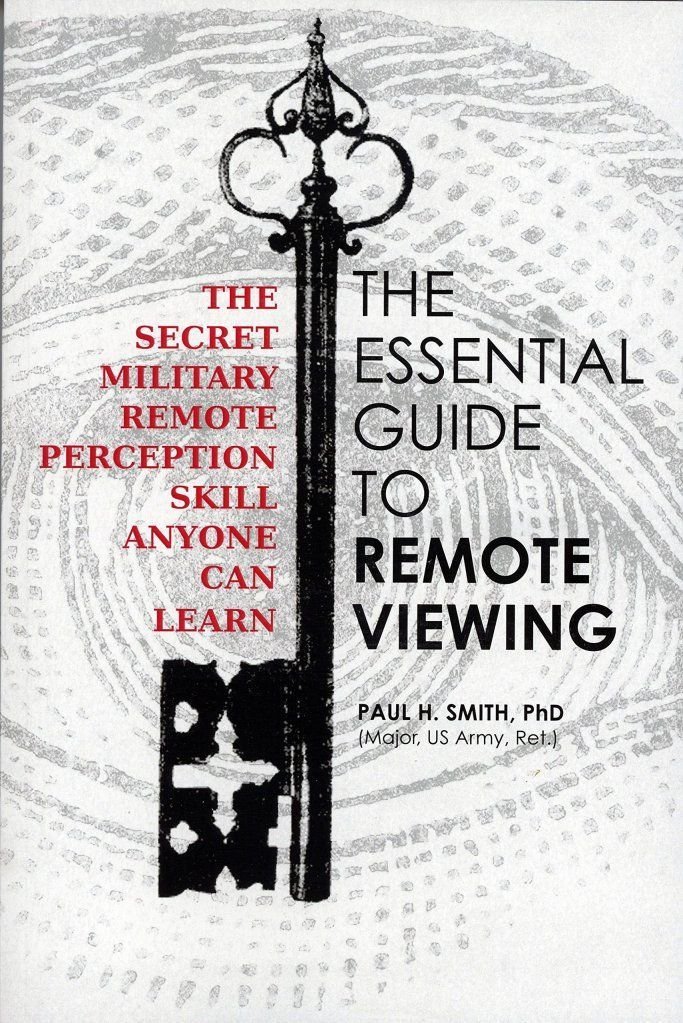

A few days later, Mr. Atwater gave Mr. Smith, who had no previous psychic experiences, the Meyers-Briggs personality type test, and discovered that he was an INFJ (Introversion, Intuition, Feeling, Judging—a personality type conducive to remote viewing). So Mr. Smith was added to the unit. He went on to literally wrote the book on remote-viewing: in the mid-80’s, he penned an Army instruction manual that has been floating around the internet so persistently that I could have sworn it was a fake when I first saw it. It was too good to be true. But it is the real thing, and it remains Mr. Smith’s lesson plan.

Looking at Mr. Smith, he seems more like the kind of guy to give sales seminars than psychic ones: he is balding with a thin Rogaine-like combover and the classic remote-viewer paunch. An active Mormon and staunch Republican who is logical almost to a fault, Mr. Smith voted for Ralph Nader in the last election because he knew that George W. Bush would carry Texas, so he figured that the more votes Nader received, the more likely he would be to run the following term and take away more Democratic votes. On the other hand, Mr. Smith is an avid heavy-metal fan, and would often try to clear his mind before Army remote-viewing sessions by listening to homemade mix tapes full of songs by Dio and AC/DC.

Today, he teaches the most popular form of remote-viewing, controlled remote-viewing, using what may very well be the most detailed psychic methodology known to civilization, the Ingo Swann method. (The other main method, extended remote-viewing, involves the subject entering a trance-like meditative state and practically going out of body to access the target. Next year, Mr. Atwater will start a course in this method at the Monroe Institute.)

Overall, the purpose Mr. Swann’s methodology is to force viewers to slow down and not make large inferential leaps as their mental connection with the target slowly widens, like eyes dilating in the light. A target isn’t revealed in a flash of insight: instead, the information comes in small trickles of data. Viewers must be taught not how to be psychic, but how to keep their analytical mind from interfering in the process. For those who believe in brain duality, remote-viewing is a right brain process. Viewers are taught to write down everything that comes to mind, no matter how ridiculous, and to not interpret what they write down and jump to a conclusion misidentifying the target. The key to success, Mr. Smith says, is to “Identify and trust your experiences,” which isn’t a bad life lesson to learn. Dr. Puthoff compares the process of remote-viewing to drilling a bunch of holes in a door until, finally, the whole door comes crashing down, revealing what’s inside the room.

More specifically, the Ingo Swann method is a six-step process: first the viewer, through an automatic scribble, tries to perceive the basic gestalt of the target and determine whether is land, water, or something man-made. Next, the viewer tries to pick up basic sensory data—texture, shape, color, smells, and sounds. In stage three, the viewer sketches and perceives advanced dimensional information. In stage four, more complex and conceptual data about the target flows in and is sorted into columns. In stage five, the viewer disconnects from the signal line and begins to analyze the information in those columns, figuring out what the words imply. And stage six involves three-dimensional modeling, not unlike Richard Dreyfus building Devil’s Tower out of mashed potatoes in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (only clay is preferred to foodstuffs). If anyone attempting to remote view stays in this structure and follows the many rules involved, advocates say it is more than 50 percent likely that he or she will nail the target.

In other words, it’s a lot of work. After day one of psychic training with Mr. Smith, all that happened was that my hand hurt—from all the note-taking, essay-writing, sketching drills, and homework. The training itself was very military, full of terms like “debrief” and “protocol” and target,” guaranteed to take any sort of magic out of a successful psychic experience.

On the third day of class, Mr. Smith drove us to a grocery store. As we walked around, Mr. Smith had us imagine what it would be like if we were remote-viewing the place: we felt the drafts from refrigerators, sniffed unripened nectarines and glazed donuts, looked at the reflections of overhead lights on the floor, felt the texture of a plastic gallon-bottle of milk, listened to quiet Muzak, and, in general, frightened the staff, who kept asking if we needed help, only to be waved away by Mr. Smith with the words, “We’re on a field trip.”

Armed with food from the store, Mr. Smith then took us for a picnic atop a nearby hill overlooking a stream. “In stage two, you’re winking around the area, so think about what’d you be seeing here,” he said. “If you encounter water, think about all the different ways you can describe it. It can be rushing, flowing, running, lapping, crashing, running, swirling, dripping, falling.”

Afterwards, we went back to the conference room at the Wellesley Suites, where our formal classes took place, and one by one went into the room with Mr. Smith to use our newfound appreciation for sensory stimuli to enhance our remote viewing sessions. Mr. Smith pulled a manila folder out of the attache case that he used in Operation Desert Storm—it still bears the black lettering “Cpt. Smith”--and hid the folder behind a music stand. This was my target, and he had assigned to it a random nine digit number. I cleared my mind, took a few deep breaths, and then put my pen to the paper. Mr. Smith read the coordinate number, 010720095, which I repeated and wrote down. I then instantly drew my ideogram, a jagged scribble, and wrote down the word “land” because the angles and curves felt sharp and natural.

“Now move on to stage two,” he said.

I wrote down the words craggy, mealy, crumbly, rising, rounded, brown, and rough. My left brain suddenly imagined a mountain, and I wrote the word down on the side of the paper, less as a guess than to excise the image from my mind. I continued writing: warm, tall, cylindrical, red, white, striped.

“Target, end,” Mr. Smith stated, indicating that somehow I had accurately depicted the location represented by his coordinates. He grabbed the envelope from behind the music stand and showed me the photos inside. It was full of images of Bryce Canyon, the mountainous national park full of crumbling red and white striped rising rock formations.

I don’t know how I feel, I told him. Although I had a one in a million probability of getting every shred of information about Bryce Canyon and other targets correct, I still didn’t know if I can make the leap and convert. “How many times does it take before you believe?” I asked.

Some people answer this question by saying that asking whether they believe in remote-viewing is like asking whether they believe in a fork: It just exists. But Mr. Smith was more circumspect. “I still wonder about that sometimes,” he said, “especially after I haven’t done a session in a long time or a student has missed a bunch of targets.”

Though remote-viewing may be the most easy-to-believe psychic phenomena, with mountains of successful experiments bearing evidence, doubts still remains. In the last month, I’ve tested out scores of people, from a Los Angeles surfer to a Yeshiva student to the wartime mayor of Belgrade (who actually did pretty well) to a painter who eerily nailed each target , and have yet to draw a firm conclusion. I do not doubt that all the former military agents I talked to truly believe that they are remote-viewing, and it is encouraging that, after more than two decades, most of them are still at it. An odd thing is that all the people I tested, even the biggest cynics and doubters, discover that deep inside they really want to be psychic once the pen and paper is placed in front of them.

But the skeptic in me says that a viewer can get acclimated to the targets: if it’s a military assignment, chances are that it’s going to involve surveying the enemy—and there are only a few choices here: draw a floor plan (of an embassy or prison); spy on a lab or manufacturing facility that involves weapons; or find the location of a missing agent or terrorist camp. If it’s a civilian practice target, it’s either land, water , or structure, and from there, one can narrow it down to a small subset of recognizable landmarks.

In addition, on a non-military level, although there is an infinite number of locations in the universe, perhaps there is only a small, finite number of sketches and gestalts that can describe them. If one simply drew a circle, whether the target was a mosque, a lake, a UFO, or a potato chip, the remote-viewing would seem like a success.

Jim Underdown, the executive director of the center for Inquiry West, a skeptic’s organization, said he had yet to see any credible evidence for remote viewing. “A rectangle could be anything from the World Trade Center to the Sears Tower to the Washington monument,” he said. “So they’re either making very general sketches and interpeting them liberally, or there’s a trick to it.”

But then again, I’m still at a loss to explain my experiences with Mr. Targ, Mr. Smith, and some of the friends I tested. It is going to be a difficult road proving what Mr. Smith describes as “a truly tenuous human perception phenomenon.” Converts can only be won one person at a time, giving them a direct experience like I had. To achieve more widespread acceptance, remote-viewers will have to not just show Cold War successes, but provide practical applications Americans can use in everyday life so that they, too, can learn the remote-viewing dictum, “There are no secrets.”

FM Bonsall, a non-military viewer who helped design a remote-viewing game called Mindazzle for the general public, says that there is too much emphasis on instruction. “Why is it that all the great remote viewers are making most of their money teaching?” he asked. “If people are going to accept remote viewing as being real, we have to get beyond just teaching. We need to solve real world problems that are beyond all elements of doubt. We need to do something that makes society sit up and take notice—like winning the lottery. It can be done and, God willing, I’ll be the first to do it.”

Many remote viewers, like Dr. Puthoff and Mr. Targ, have made good money in the silvers futures market through remote-viewing, they claim. Since remote-viewing actual numbers and letters is difficult, this is done through a process called Associated Remote Viewing. In trying to guess the direction a certain stock will move in, for example, someone can assign a random object or event to each direction: a tennis shoe would represent the stock going up; a vase going down. The viewer (or better still, a team of viewers) is then asked to predict the future by drawing the object they will be shown at 5 p.m. the following day or week. If the viewer or viewers draw a definite shoe or vase, then the investor proceeds accordingly. And, finally, at the appointed time the following day or week, the viewer is shown a tennis shoe if the market went up and a vase if it went down. And, if they’ve managed to remote-view their own future correctly, someone will have made a lot of money.

Mr. Buchanan say that although the United States seems to have ended remote-viewing espionage, other countries may have such programs. He predicts that remote viewing will eventually succeed in leaking into everyday civilian life—thanks to get-rich-quick aspirations, parents trying to figure out where their children are at 2 a.m., corporations spying on each other, and more. “Then the kid is going to die,” he says. “It will be the kid who always dies—the one who died playing with the yo-yo when it first came out, or playing Dungeons and Dragons, or listening to Elvis Presley’s ‘jazz.’ And then the preachers are going to preach against it, the teachers are going to teach against it, and there’s going to be a witch hunt and remote-viewing is going to go back into the closet. And then, when it goes back in the closet, the government is going to start using it again.”

This will probably happen within the next 20 to 30 years, Mr. Buchanan added. And what exactly makes him so confident that this will happen? Well, he answered, he remote-viewed it.